Many of you will know Budapest’s main streets and squares, their familiar façades and landmarks. But walk for ten minutes in any direction and you’re soon in terra incognita, thoroughfares where every other building has a plaque related to some historical figure or event, an unusual statue, a stunning church. Such is Lövölde tér, at the crossroads of lively Király utca and leafy Városligeti fasor, peaceful Szív utca and busy Rottenbiller.

Lövölde tér is located where Király utca runs out of road. Its funky little shopfronts displaying diving equipment, secondhand books or T-shirts for long-forgotten metal bands will be fading into the memory as you approach this busy junction.

As a square, Lövölde tér mainly comprises a lively children’s playground, a four-star lodging and a Tardis-like green building which we’ll come to shortly.

Unless you’re a five year old in need of a swing, a guest at the Smart Hotel Budapest or Doctor Who, there would seem little reason to venture this far down Király utca. But explore a little, scratch the surface, and you soon uncover a wealth of hidden intrigue, tragedy and urban myth.

Lövölde tér is named after the shooting range that once stood here between 1840 and 1890. This being Habsburg Budapest, it was a rather grand affair, all Doric columns and cigar lounges, but with flats in ever greater demand, marksmen soon had to take their skills elsewhere.

The location gained its name, ‘Shooting Square’ in

1874. Today it still delineates the district borders between comfortable Terézváros

– showcase Andrássy út is close by – and Erzsébetváros, traditionally Budapest’s Jewish Quarter.

Walk a few blocks towards town or ride three stops on red trolleybus 70 or 78

from the green Tardis and you’re surrounded by ruin bars and memorials linked

to the Budapest Ghetto of 1944.

Here, somewhat prosaically beside the Lidl supermarket,

stands the building that once housed the Kairó Kávéház, a popular café in the early

1900s. You can see a postcard of its Oriental-style interior here.

According to one eye witness, statistician György Surányi, a boy when his family were regulars here:

Kairó kávéház

“The cafe was very long and narrow because towards Király utca, I think there was only one window… there were tables in two or three rows, and there was room for the waiter in the middle. There were small tables for four, slightly larger for a card. They were cafeteria chairs, thonet chairs. Craftsmen and retailers also went to this café, and there were some beggars and ladies of ill repute, but whoever came in wasn’t sent away, just found the right table during the day. There were big card parties. Some of the regulars were rich enough to play for very big money, I remember. There was a pool table, they also played billiards. But almost the whole café was full of card parties”.

Another regular was Pál Teleki, later prime minister of Hungary, who shot himself on the eve of the German invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941.

A few buildings along Szív utca, a plaque commemorates the house where famed

author Arthur Koestler was born in 1905. Later based in London, this journalist,

spy, soldier and political activist led an extraordinary life, leaving Terézváros

to study in Vienna, work in Paris and Berlin, travel extensively around the Soviet

Union during the pre-war Purges, report from the North Pole, join the French

Foreign Legion and undertake secret undercover work for the British government.

In between, he was sentenced to death during the Spanish Civil War and wrote his

most famous work, Darkness at Noon. He committed suicide in 1983, at the same

time as his English wife.

Koestler’s statue, one of the last works created by award-winning sculptor Imre Varga, sits on this side of Lövölde tér. In his lap, one hand is placed over a book upon whose cover runs a single word, in English and in block capitals: DARKNESS.

His collar turned up, Koestler looks askance across the the two halves of the square, divided by a busy road that leads up to City Park. Városligeti fasor runs arrow straight to the new Museum of Ethnography, past elegant villas, one housing the György Ráth Museum, and embassies, including the Chinese and Indonesian.

Close to Lövölde

tér, the Budapest Fasor Reformed Church was built by Aladár Árkay between 1911

and 1913, at the tail end of the Art-Nouveau era. The architect brought in the two

most famous names in ornamental design – Zsolnay and Miksa Róth – to decorate

the building.

The exterior shows a colourful array of pyrogranite

cladding inspired by Hungarian folk art, as created by the famed tiling manufacturers in Pécs while the stained-glass windows were the handiwork of mosaic master Miksa

Róth.

The same church, the same playground and the same trolleybus can all be seen as they looked nearly 40 years ago thanks to a video by actor and singer András Kern. Performing his own song titled, quite simply, Lövölde tér, the clip shows Kern strolling around the square, sweeping leaves and looking glum. This was 1985 and it was raining.

His song was later covered by various artists including currently popular Gypsy swing merchants, Budapest Bár.

Presumably

because it was thought to be in bad taste, the camera didn’t swing a little

further round to capture the mysterious, green, Tardis-like building on one

corner of Lövölde tér.

Still here today, this is actually a public toilet. Few from this era can be seen around the city so this is like finding one of the last red phone boxes in England. Locals used to refer to it as the green tram as it resembled the earliest carriages to trundle around town, before the age of yellow descended.

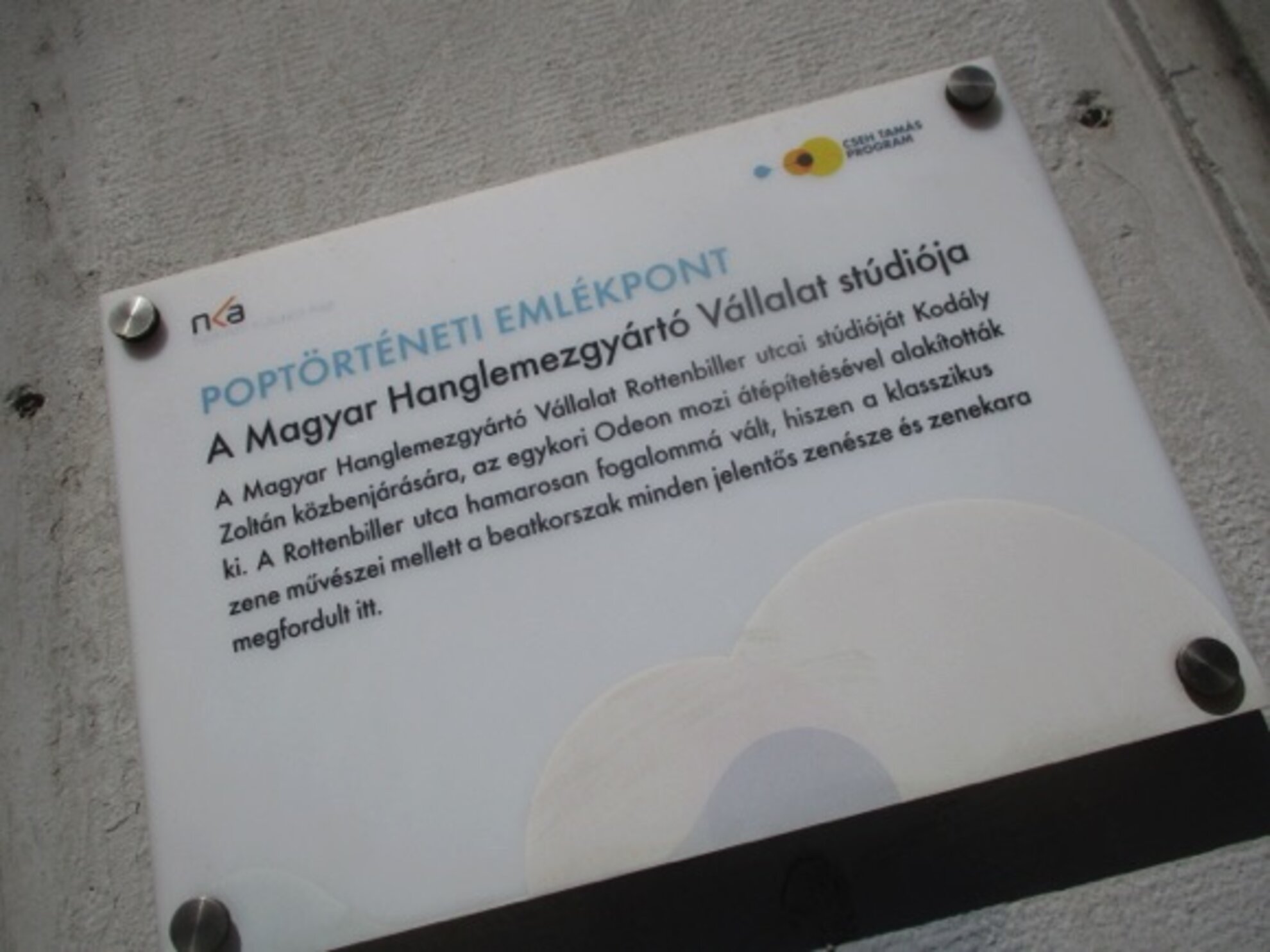

There’s one more sight left to see: Abbey Road. Or rather, its Budapest equivalent at Rottenbiller utca 47, where former state-run record company Hungaroton had its studio.

After the private ones were subsumed into this one nationalised entity in 1951, none other than composer and musicologist Zoltán Kodály himself – who lived close by on Kodály körönd at the other end of Szív utca – oversaw the creation of a recording studio in the ground floor of the former Odeon cinema, now a residential block.

For decades, the cream of Hungarian pop and rock

would come here to cut their latest record, to be released on the Hungaroton,

Qualiton or Pepita label. Pressing was done elsewhere, for a time at the more

sophisticated Czechoslovak Supraphon factory. Before then, only a thousand or

so of each disc was published, making them collector’s items today.

A plaque (Pop

History Memorial) marks the doorway where beat-era heroes Illés, Metró and Omega would have strode through purposefully before laying down another tune for the kids

to dance to at the Ifipark.