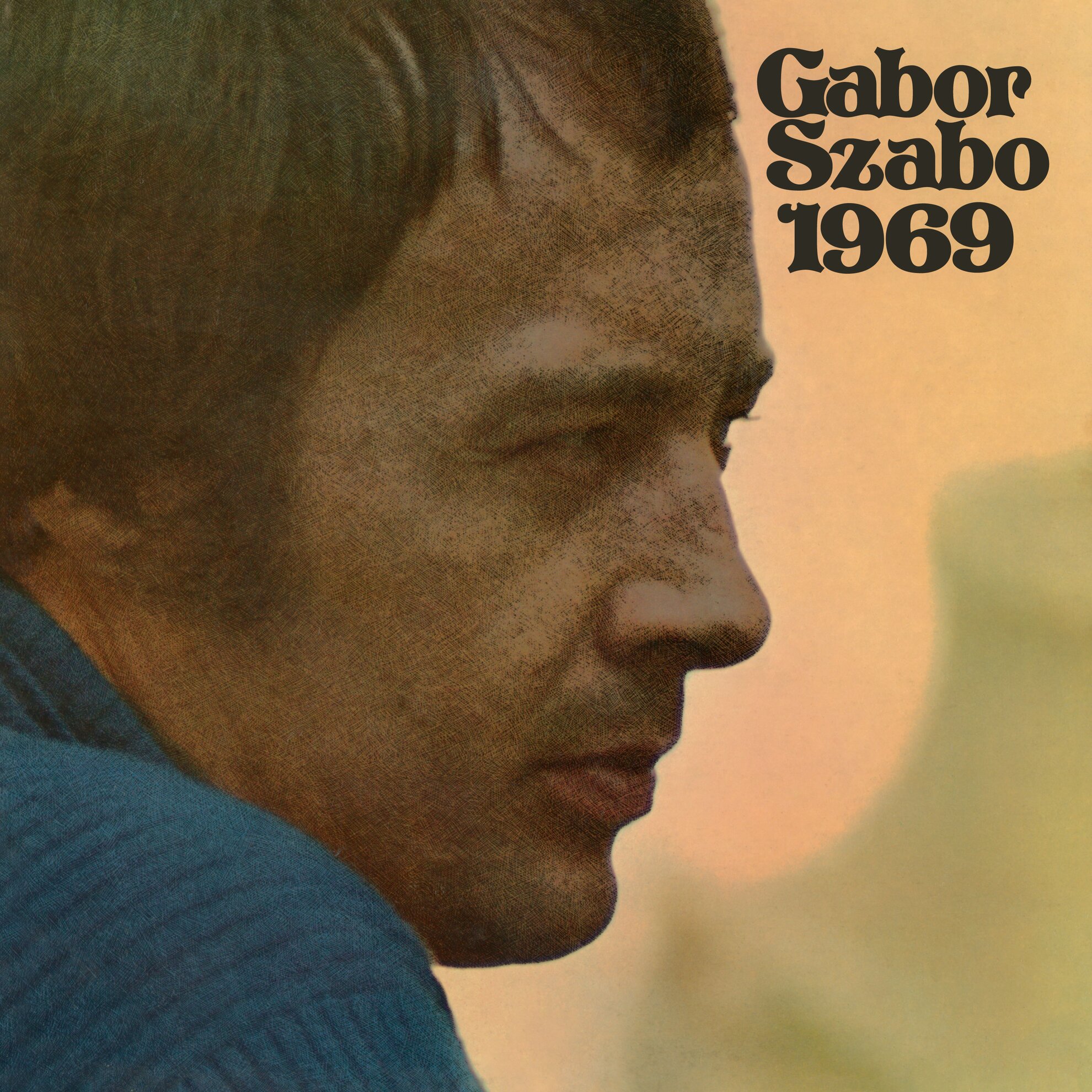

Admired by Jimi Hendrix, revered by Carlos Santana, Hungarian jazz guitarist Gábor Szabó died 40 years ago this week after collapsing on a street in Budapest. A wayward genius who rose to fame in the 1960s, Szabó left Los Angeles a decade or so later, in poor health. Now Hungary-based UK writer David Holzer and US magazine editor Mike Stax are pooling their talents to write a joint biography, aiming to redefine Szabó’s legacy.

“Gábor Szabó takes some time to sink into your musical consciousness,” begins UK music writer David Holzer, explaining how he started on his own journey into the unknown. “But when he does, if you’re a certain kind of person, you recognise the sound of Gábor within two or three minutes, which is always the sign of somebody doing something very different.”

Dividing his time between Szeged and Mallorca, Holzer has written more than 20 books on everything from the Beat Generation to yoga. He has his jazz-obsessed brother to thank for introducing him to the mystical music of Gábor Szabó.

Groundbreaking Gábor Szabó

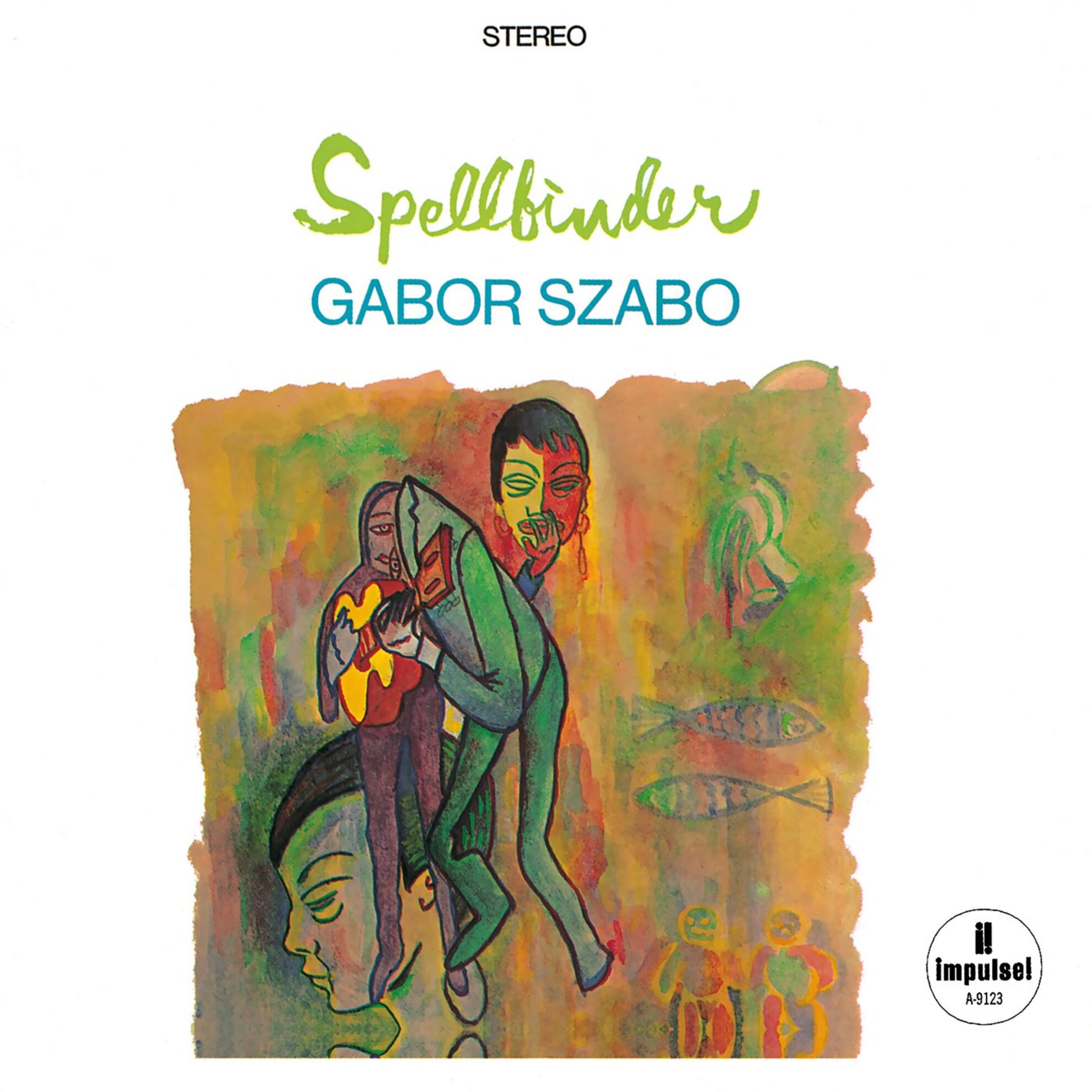

“I first listened to the albums Jazz Raga and Spellbinder and realised he was a groundbreaking musician who’d pretty much been overlooked. Ted Gioia’s History of Jazz, for example, doesn’t even mention him once, which I find extraordinary.”

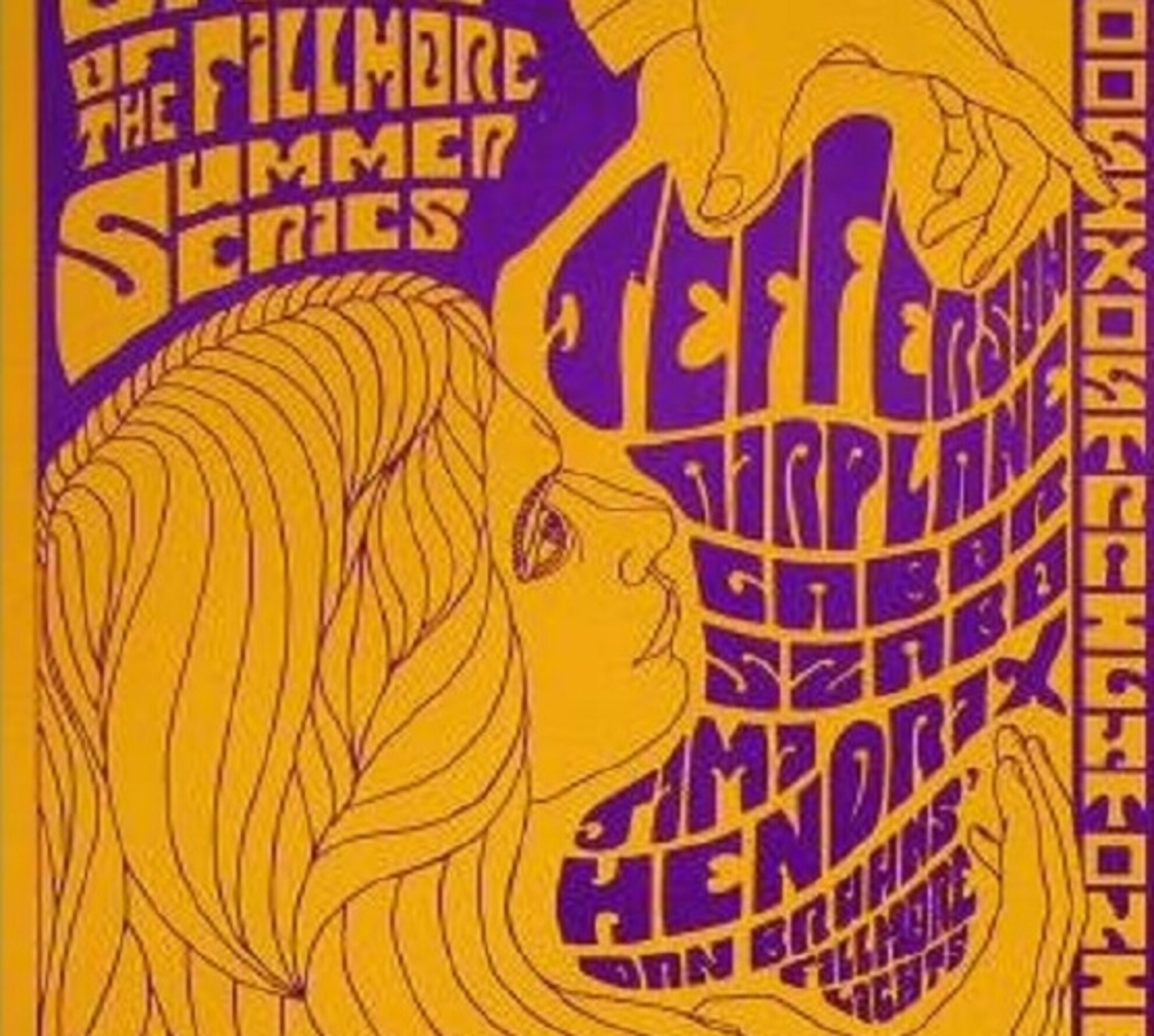

And yet Gábor sold out a two-week residency at the legendary LA jazz club Shelly’s Manne Hole and shared the same bill at the Fillmore with Jefferson Airplane and Jimi Hendrix. He is said to have influenced Robby Krieger of the Doors and the raga guitar sound you hear during The End. He made albums with Lena Horne and Bobby Womack, with whom he also created the original and arguably best version of Breezin’, a later hit for George Benson.

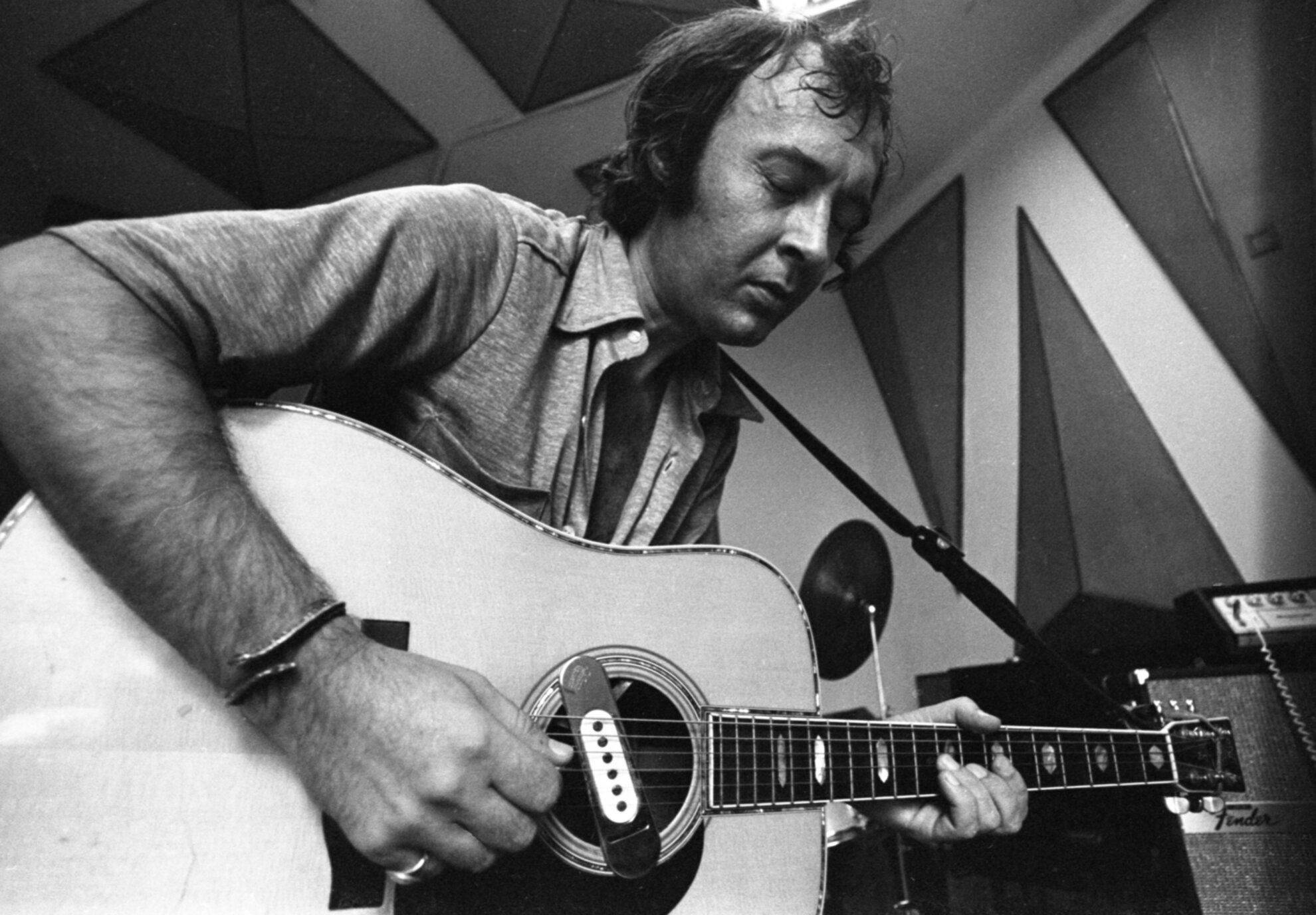

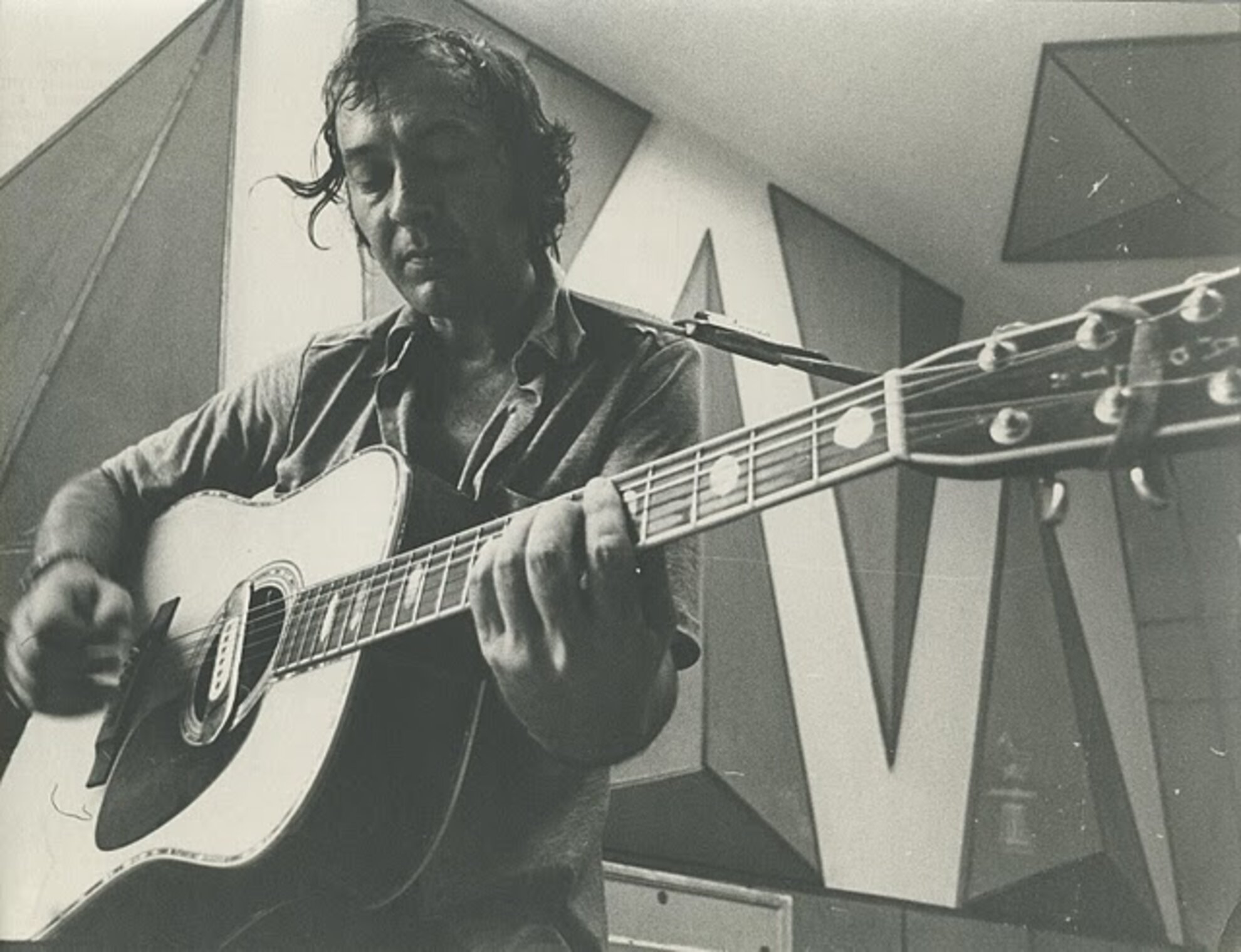

“Some people refer to his music as Hungarian Gypsy, but it isn’t that. Pure jazz fans tend to look down their noses at him. It sounds deceptively like smooth jazz, but listen harder, and it’s not as smooth as you think it is. It makes you want to hear more. You only need to look at a photograph of Gábor in his ill-fitting suit, hunched over his guitar at the Newport Jazz Festival, utterly focused on his music. People would fall in love with him on the spot. It was as if he was casting a spell on them.”

A regular contributor to Ugly Things, a US music magazine championing hidden gems of the classic rock and pop era, Holzer tentatively suggested to editor, Mike Stax, that he write an article about this obscure Hungarian guitarist he’d stumbled across.

“It turned out that Mike was a huge fan, too,” says Holzer. “He’d already

written a book about another 1960s’ casualty, Craig Smith, and we discussed a potential

collaboration about Gábor, each focusing on different areas of his life.”

Swim

Through the Darkness had taken Stax on a 15-year quest through some pretty uncharted waters so he knew

all about the strange detours a musician's story may take.

For Gábor, as for so many thousands of Hungarians, his major detour came in 1956 when he fled his homeland for America in the wake of the anti-Soviet Uprising. He was then 20 years old.

The Budapest-born son of a quarry accountant who later made wall lights for the Opera House, Gábor had gone to school in Sóskút, south-west of the capital. Holzer is keen to hear from anyone who might have known him during his formative years of the 1940s and early 1950s, particularly during the war, when Gábor would have still been a boy. By 1951, still only 15, he was playing with the Sándor Argényi quintet at the ÉDOSZ club.

Jazz in Budapest

“Gábor loved the whole jazz ethos,” says Holzer. “He listened to whatever he could and read any copy of DownBeat magazine he could get his hands on.”

US-influenced jazz was frowned upon in Communist Hungary, so much so that spies would go from café to café, making sure that Western music didn’t make up too much of the repertoire. The quintet also appeared at the Tóterasz at City Park, overlooking the lake. Like Gábor, Argényi fled in 1956 and would later set up a jazz club in Sweden.

Until the Uprising, Gábor was also in a trio with singer Éva Vigh, doing standards in English, though not at public concerts. Together, Gábor and Vigh escaped Hungary, along with their friend, Tibor Gyimesi.

“The arrangement was that Gábor’s parents would follow him, bringing their youngest son, John. They got across the border and met up by chance at a refugee camp. Then they all went to America together.”

Gábor became the stand-out student at the renowned Berklee College of Music – alma mater of Al Di Meola and Keith Jarrett – and was invited to join Chico Hamilton’s group. He played with Chico for around five years, began to develop his own sound, and recorded eight albums before leaving.

He then played with sax and flute player Charles Lloyd, collaborating with composer, arranger, vibes player and vocalist Gary McFarland before striking out on his own. His first albums were on Impulse!, hallowed label of John Coltrane.

The unique sound of Gábor Szabó

“Like Charlie Parker before him, Gábor spent time in the wilderness and came back with a sound that nobody else had,” says Holzer.

Gábor’s second album, Spellbinder, released in 1966, is considered a classic and contains the track Gypsy Queen later covered by Santana. “The real jazz musicians like Charles Lloyd got Gábor. Carlos Santana said that he took you somewhere else.”

The guitarist became a big name in Los Angeles – “he lived on the same Hollywood street as Elizabeth Taylor” – and played all the key venues. The West Coast was the epicentre of the music industry and sunshine pop ruled the waves.

While Gábor embraced several genres, he remained undefinable. “It isn’t pure jazz, it isn’t pop, it isn’t rock ‘n’ roll,” explains Holzer. “He experimented with raga and also feedback. He wouldn’t use it to disrupt, like The Who, but he would get a sound and then let it ride.”

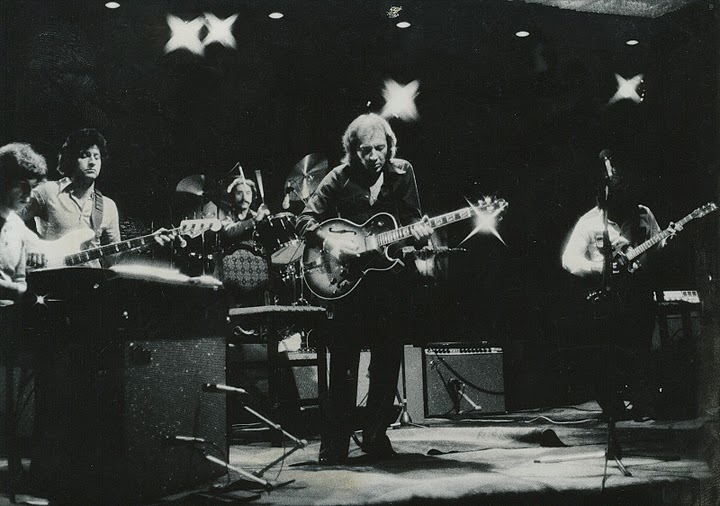

Gábor and Jimi Hendrix were on the same bill at the Fillmore and bonded backstage over a love of Wes Montgomery. “Mike was speaking with his bass player that day, Lou Kabok, who said that Szabó came out and played so loud, it was louder than a Russian tank!”

Gábor not only experimented with sound. “He embraced the whole jazz lifestyle and developed a terrible drug problem. People I’ve interviewed say that he was still terrific to work with in the studio but you could say that he blew it, in terms of success.”

Gábor first came back to Hungary in 1974, played the Culture House on Marczibányi tér and gave a TV interview, later rebroadcast several times.

“As he’d made his name in the States, Hungarians didn’t know him that well. You couldn’t really buy his albums here.” He returned later that same decade to play at the Hilton Hotel. Estimable label Moiras Records, which specialises in Hungarian beat and garage bands of the Socialist era, has since issued live recordings of Gábor’s Budapest performances.

By the time Gábor returned in the early 1980s, he was undergoing hospital treatment for liver and kidney failure. Eventually he collapsed and died on 26 February 1982. He was 45. He lies buried beside his mother in Farkasréti cemetery.

“I think he was really angry that his health was giving up,” concludes Holzer, who is in touch with Gábor’s younger brother, John. “We would have had decades more of his music. How would I define his legacy? Quite simply, untapped.”

Recently, however, Danish psych-rock band Causa Sui released an album

called Szabodelico directly influenced by the Hungarian guitar genius – there’s even a track

called Gabor’s Path.

Maybe it’s high time for a Gábor Szabó revival?

David Holzer and Mike Stax acknowledge the generous help given by US jazz writer Doug Payne, who has created his own online bio of Gábor Szabó.

Information wanted

David Holzer would be keen to hear from anyone in Hungary who has any memories or first-hand details of Gábor Szabó, particularly in relation to his formative years in Hungary. Contact him via davidholzer.com.

Gábor Szabó’s grave is at 36/2 in Farkasréti cemetery. From the main entrance, walk up the main path from the noticeboard and turn left at the small roundabout.