In recent years, there has been a renaissance of classic barber shops in Budapest, a men-only domain of playful camaraderie. Essentially, a tradition dating back to the Middle Ages has been revived. Above the entrance, twirls a barber’s pole of red-white-and-blue stripes, an apparent nod to the times when barbers would hang hang blood-stained cloths on a rod.

When barber’s shops operated in the 13th century, they not only cut hair and shaved faces, but also functioned as surgeons: if necessary, they cut blood vessels, pulled teeth and even examined the dead as medics during epidemics. Until the 18th century, they performed these tasks with reasonable success, as their competence was not questioned or overseen by anyone.

Then, in the time of Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa, an attempt was made to control the monopoly of these would-be physicians and, with the establishment of the University of Trnava, medicine and barbering were finally divided. The diverse tasks of barbers were given over to examiners who assessed each patient by a process of investigation.

Fortunately, it was around this time that wigs became popular and hair curlers became fashionable, endowing barber shops with a new range of activities – the word ‘hairdresser’ came into existence, and haircuts and hairstyles were separated from the 18th century onwards.

Fortunately, it was around this time that wigs became popular and hair curlers became fashionable, endowing barber shops with a new range of activities – the word ‘hairdresser’ came into existence, and haircuts and hairstyles were separated from the 18th century onwards.

The Hungarian Barber and Hairdressing Assistants’ Association was founded in 1904, and they wrote in the Barber and Hairdressing Assistants' Journal once a month until World War I. In 1922, a law was passed stipulating that women's and men's hairdressing were two separate professions, and from 1938, a law tied the trade to the operating in business premises.

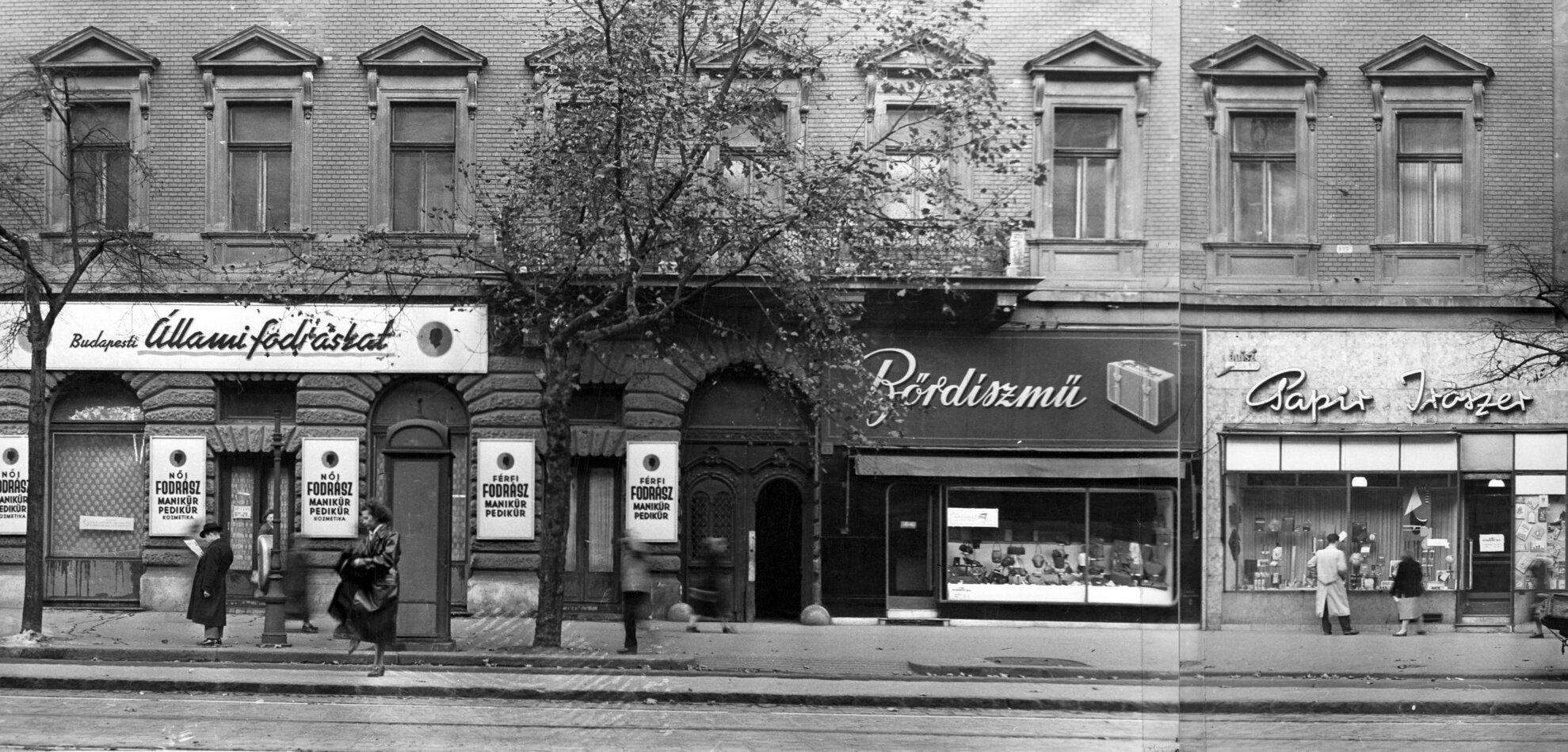

After World War II, about 20,000 hairdressers worked in Hungary, but the nationalisation completely transformed the industry. In 1950, the salon on Csáky utca was first in Budapest to come under state control, then the two largest hairdressers in Budapest, on Petőfi Sándor utca and Múzeum körút.

The Budapest State Hairdresser’s was established with seven outlets. By 1970, they numbered 112, offering so-called Annabel bobs and COSI cuts with curls, rings and waves.

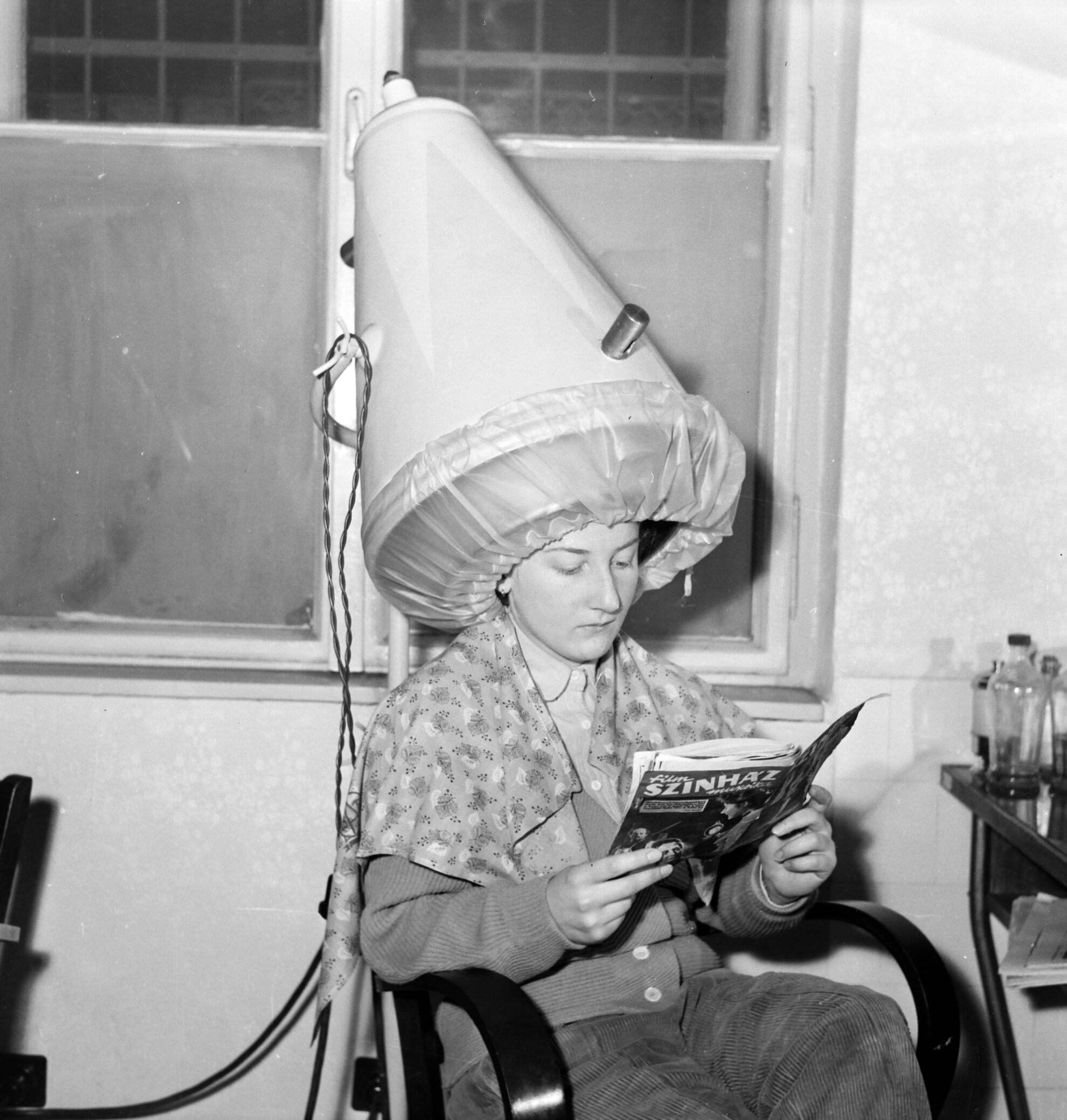

The company's central building was in downtown Gerlóczy utca, and its corporate resort was in Balatonkenese. There were also cosmetics in the large, hall-like huts, where “various vitamin, paraffin, oily, sulphure wraps make the skin supple. The Solux lamp, which can also be found in the company’s showrooms, has a healing effect. Along with the finish, a complete cosmetic treatment is barely an hour, not too much to sacrifice of so much for beauty and health,” said one article in a 1970 edition of Figyelő.

In addition to the salons of the State Hairdressing chain, co-operatives were formed one by one from the hairdressing tradespeople who feared nationalisation, and by the 1960s there were already nine such organisations.

For example, the Venus Hairdressing Co-operative in Budapest had 84 outlets in Districts VII, XVI and and XVII. From the 1960s, there were also private hairdressers, but these were at a great disadvantage in the procurement of tools and raw materials.

There’s essentially no difference between the present day and Socialism: unfortunately, there less competent hair stylists were more numerous back then, and when the reputation of an exceptionally good one went up, they were oversubscribed. It was worth for any sought-after snipper to switch from the state to a cooperative operation or even a private one, the customer base duly followed.

As at traditional barber and hairdressing salons, various ointments could be bought in the state-run outlets, while wigs and extensions made of real hair could also be obtained. The 1969 issue of Figyelő wrote that hairdressing-related services, hair-care and beauty products were of Western standards:

Hair care at a snip

“At any of the 112 state-run hairdressers in the capital, anyone can find and try the best Swiss hair-care products to suit them. For these excellent products, not only do you not have to travel to the West but you also don’t have to be rich. Namely, the State Hairdressers, using agents bought with foreign currency, have introduced special services at relatively cheap prices, from nine to 15 forints. These include: PAR-O-STAR for hair loss, PAR-O-SCAL for dandruff and PAR-O-DRY for greasy hair. These products can only be found in the state-run chain.”

As for those looking to lose weight as well: “The company's cosmetics salons on Engels tér and Petőfi Sándor utca are equipped with modern facilities purchased from Switzerland, consisting of a sauna, a massage machine and a mechanical shaking machine. The main advantage of this equipment and its use is that it takes off the extra pounds from where the guest wants them, and where they’re least needed. There is a dressing room for ladies in the salon. You can take a shower after the massage. After the treatment, hair loosened by the steam of the sauna can easily be combed.”

Great shaves

“From 1957 onwards, services began to develop swiftly but this did not last too long. Slightly untidy hair, curled according to fads, came into vogue. With your own electric razor, you could shave away the bristles at home effectively, cheaply and very quickly. For example, in a hairdressing salon in Cologne, only one employee is said to be able to shave professionally. The need for this service has simply disappeared. In several public places, there are vending machines for men who want to shave: for twenty pfennings, they rent an electric razor for a few minutes,” complained the author.

In 1975, the introduction of Sunday working changed the mood in the shops of the state hairdressers, 16 of which had to stay open in Budapest. A contemporary article in Népszabadság revealed that hairdressers had a hard enough time being on the job for 12 hours on a Saturday without having to be back in the saddle until the early afternoon the next day.

Weekend trade was slack anyway, because women preferred to go to the hairdresser’s at the beginning of the week rather than on Saturdays and Sundays. “Store manager Mrs Lászlóné Szőnyi brings out the complaints book. It only contains entries dated on a Sunday. The complainants suggest that after 11am, the hairdressers no longer take on more customers, and are rude and ‘skittish’. And there is also an entry in which a doctor from Buda says that half of them did not undertake manicure”.

The

problems of the Socialist system became apparent in the hairdressing industry

as early as the mid-1980s: there were too many salons, few good ones, and they all

made a loss. The first sign of decline was that in 1985, State Hair Salons were

reorganised into small businesses.

In addition, the state withdrew support from

small-scale co-operatives and provided an easier path for private enterprises.

After the change of régime in 1989, the obsolete companies and premises of the

already small and unprofitable State Hairdressers were privatised, and the era

came when people could choose from a myriad hairdressing salons or larger franchises.

Sources

István Bogdán: Old Hungarian Trades, Neumann, 2006

Hungarian Catholic Lexicon

Figyelő, July-December 1969 (13th year, editions 27–53)

Figyelő, 2 April 1970 (edition 13)

Csaba Osgyáni: Fodrászok – fodrászatok, February 1971 (9th year, edition 2)

Népszabadság, 7 December 1975 (33th year, edition 287)

Népszabadság, October 1984 (42nd year, editions 231-256)