The plague is usually considered to be the most horrific of epidemics, although smallpox and, these days, malaria carry more of a threat because of their insidious spread. Of course, the first and largest plague of 1347-53 took many casualties, halving the population of Europe, though later ones were less devastating. Smallpox claimed half a million victims each year and those who survived either lost their eyesight, such as Ferenc Kölcsey, writer of the Hungarian national anthem, or were scarred for life. However, thanks to effective vaccines, this is the only contagious disease that has been eradicated from the face of the Earth.

There was one pandemic across in all continents of the world, one of the very virulent of influenza types, Spanish flu, first contracted by soldiers during World War I. It arrived in Hungary in the summer of 1918, with a mortality rate of 10% by December. Similar measures to today were taken at that time: public transport was forbidden to those who were sick or without a mask, cinemas, theatres, nightclubs, universities and cafés were closed, and the few public telephones had to be wrapped in tissue paper to be used. The epidemic caused more casualties than conflict itself. Two million people died in Europe, 25-50 million worldwide. This was the most devastating epidemic in the modern age, but in the Middle Ages the situation was much worse, with poor hygiene and health conditions, and lack of basic information.

Even in ancient times, people suspected that infections were spread by invisible things, ‘tiny kernels’, and they knew quite well which disease was contagious and which was not. Until relatively recently, though, but they didn’t get to identify them. The science of bacteriology was born in the 1870s, which made it possible to detect microorganisms under the microscope. From then, it was possible to identify bacteria and viruses, and this was when drugs and the first vaccines were born (except for smallpox, because vaccination against it did not start in Europe until the 18th century).

Thus, in search of reasons, contagion was considered a divine judgement on people’s sins. Extreme solutions to this were found by the supporters of the flagellation movement, who, during the first plague of 1347-53, wandered around communities en masse in apologetic self-thrashing to put an end to the epidemic. This happened across Hungary and the rest of Europe.

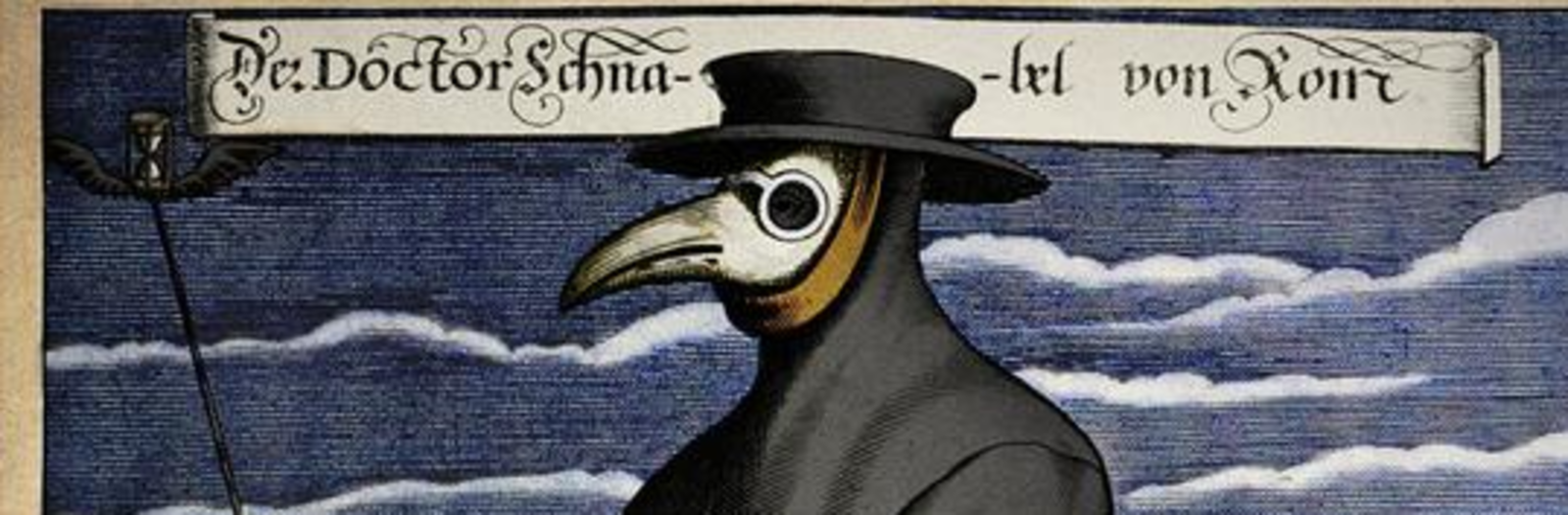

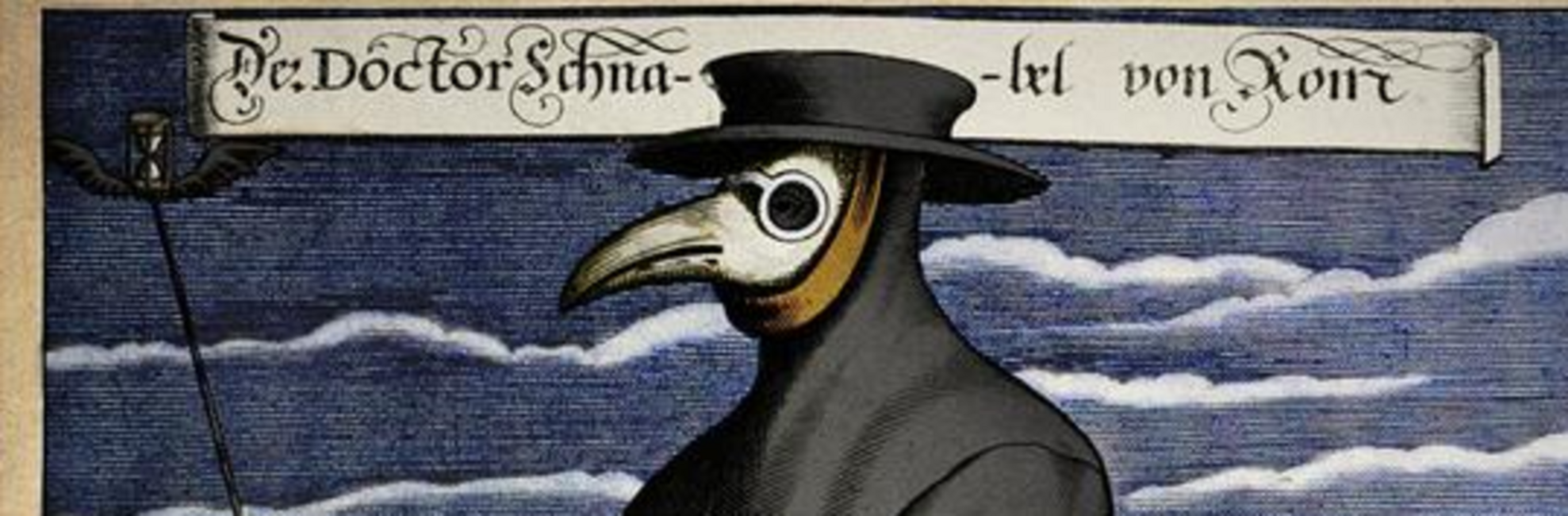

Or, one step closer to reality, they attributed the illness to poor air quality. They tried to counteract this with various fragrances and smelly aromas, and people were also thrown onto large public fires, thus ‘disinfecting’ the air. They even used vinegar and a plague mask, a concept familiar to our readers today, was introduced from the 16th century, with herbs in its beak. Interestingly, this worked, not because of the plants, but the full protective clothing – this was essentially the first gas mask. There were many magical cures that can be found even in the medical books of the day. Attempts were made to prevent the outbreak by using amulets, talismans or little magnets of arsenic, which, fortunately, were only placed externally on the patient's body to expel the disease. The plantain plantago major was used against plague but only because of its name, útilapu in Hungarian. Papal grass, also known as Benedek grass, after the healing power of St Benedict, was another.

However, humanity, in addition to confusing theories, without any knowledge of microbiology, was able to recognise that the spread of contagious diseases was through human contact and trade routes. This resulted in the emergence of a public health system. Epidemics were closely linked not only to famine, but also to wars and the mass movement of armed forces. Dysentery was one such military illness – during the Siege of Vienna in 1529, many of Suleyman’s troops died of what was called morbus hungaricus, a term also applied to tuberculosis.

Even when the first major plague epidemic occurred in the 14th century, the concept of quarantine was created, the first in 1374 in Venice for 30 days (trentina), and then down the Adriatic coast in Venetian-influenced Dubrovnik for the later familiar 40-day quarantena – both terms coming from the Venetian language. Closer to Hungary, the first record of a city isolating itself and escaping the plague dates back to 1510 in Sibiu, Transylvania. There is also evidence that Pest and Buda even protected themselves against each other during the plague of 1738.

In addition, attempts were made to isolate the infected – initially in their own homes, later in the 18th century, separate zones and epidemic hospitals were set up. After the plague of 1738, during the reign of Maria Theresa, stations were set up from Transylvania to the southern border of the Habsburg Empire, quarantining all merchants from the East for months, causing no little damage to business.

From the end of the 17th century, centralised public health provisions were introduced to curb epidemics, providing more protection than at the most local level. These would have been effective if they had not faced intense resistance from the population. According to written sources, people often did not adhere to quarantine. There were always renegades who fled the health cordons set up around counties and communities. Separated from their own homes, they tried to escape the surrounding infection, while those isolated in hospitals complained that they could not care for suffering family members.

Illnesses were mostly concealed because settlement closures had serious consequences for people’s livelihoods and the majority who worked in agriculture could not get to the fields to harvest the crops. In addition, patients were expelled from the community, and entire families were driven out into the woods around villages and left to their fate. During the first major cholera epidemic of 1831 (one of whose famous victims was writer Ferenc Kazinczy and one of its government commissioners was a young Lajos Kossuth, the later statesman), a rebellion broke out because of fear of livelihoods. Desperate peasants attacked landlords, doctors, priests and anyone in authority.

Only in the case of major national epidemics were central, large-scale precautions taken. People learned to live with the annual flu or pox. In the 18th century, four or five major epidemics, typhoid, plague, diphtheria, smallpox or dysentery (and cholera from 1831) raged through Hungary every ten years, typically retreating in summer. They were also periodic: as a community became immune to a particular disease, it disappeared for 20-30 years, but as the later generation was no longer protected, those epidemics then re-emerged – the plague attacked inhabitants every two or three decades.

So in the times before bacterial research and vaccines, quarantine was a solution against major epidemics. Interestingly, however, the spread of the plague was curbed long before the invention of antibiotics, as the rat population in Europe was replaced during the Thirty Years’ War: the Norwegian rat displaced the domestic variety and plague-carrying fleas could no longer colonise.

Not only regulations during epidemics, but the development of urbanisation in the 19th century, a sewerage system (necessitated by the cholera epidemic), the appearance of proper toilets (referred to in Hungarian as ‘English WCs’) and the improvement of hygiene all contributed to the disappearance, or at least a radical reduction, of major epidemics.

With many thanks to the Semmelweis Museum of Medical History and chief curator Ildikó Horányi for their help in creating this article. For more on Semmelweis and his wise words on how to wash your hands, see here.