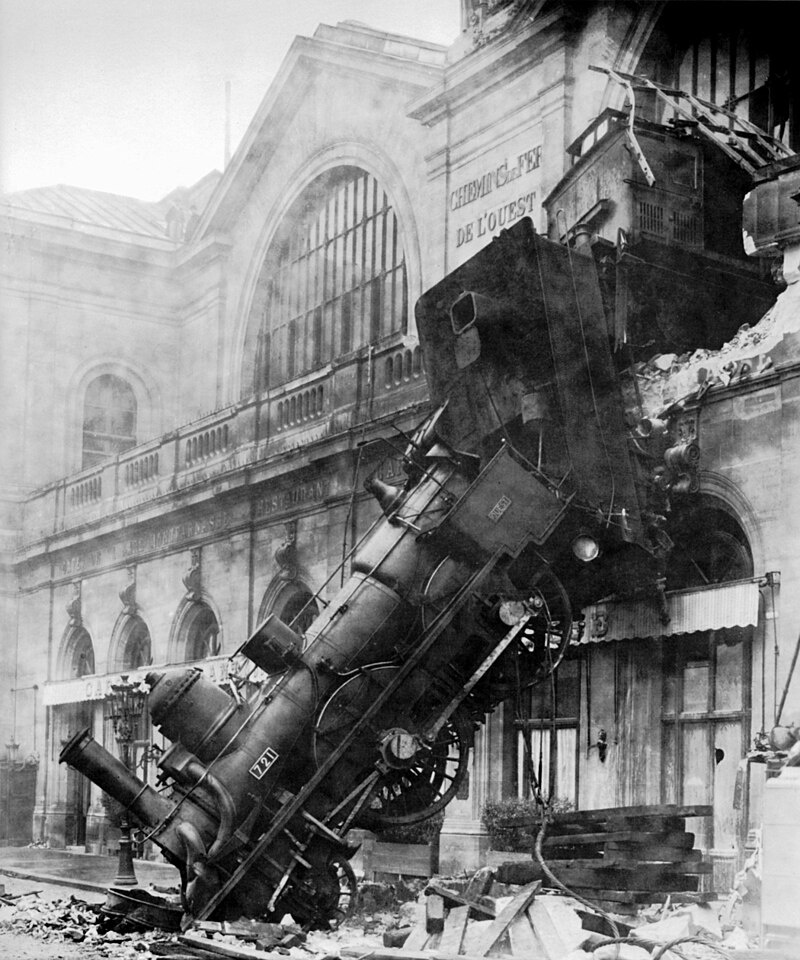

October 4th, 1962, was a day like no other in Budapest. The country was at the gates of Kádárism (a.k.a. 'Goulash Communism', the variety of state socialism in Hungary following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, with higher living standards), and a softer alternative was slowly replacing total dictatorship. The fierce competition between the two political poles of the world and the Russian-American space war was already in full swing, and the Cuban missile crisis loomed large, which almost led to World War III. Meanwhile, in Hungary, the nation's football dreams were shattered as the promising 1962 World Cup journey ended in a heart-wrenching 1-0 loss to Czechoslovakia in the quarter-finals. While The Beatles were taking their formative steps in England (having already existed for two years), Hungary witnessed the birth of its own musical powerhouse – the Omega rock band. But the most important event was an accident at the heart of the capital, at the Nyugati Railway Station and the square in front of it, reminiscent of the French train disaster in October 1895.

Both trains broke loose beyond control, breaching station boundaries and ending up in the open street. There was a difference, however: the French train fell from the platform, while the Budapest counterpart collided at street level. Remarkably, while there was one fatality and several injuries in Paris, Budapest experienced a relatively fortunate outcome with only one person injured. The root of the cause was different too: while in Paris, the accident was caused by brake failure, in Budapest it was human error, which was rightly punished.

On October 4th, 1962, the accident occurred during the afternoon rush hour, a few minutes before half past two. At 4.45 p.m. a train scheduled for departure from platform 4 at Nyugati station to Szolnok awaited its turn. The necessary preparations had been executed smoothly with the train pushed onto the track two and a half hours earlier by a shunting train from storage platform 6. Everything went according to plan and protocol. However, despite the seemingly flawless start, the course of events took a turn due to errors committed by the crew. The experienced shunter made a critical error, assuming everyone else was as skilled. The new guard, just starting that year and working with unfamiliar colleagues, also made mistakes.

The train, consisting of 10 connected wagons, was standing on storage track 6 when the shunter instructed the guard to place the steam locomotive and the attached caboose into the formation. He did not, however, give specific instructions to the new colleague to check that the locomotive and the caboose were properly coupled after they had collided with the train. They were not, so when the train transitioned to track 4 after the locomotive had braked, it failed to halt and instead relentlessly rolled on at a speed of 25 km/h. It broke through the glass wall of the station, smashed down the stairs, knocked over a support post, and continued along the pavement to the edge of Lenin Boulevard (now Teréz körút). Only one pedestrian (P. Jenőné, a resident of Csepel) was swept away by one of the cars, but she was rushed to the hospital so quickly that immediate surgery saved her life.

The absence of a major tragedy was not only due to sheer luck but also to the fact that the railway staff spotted the accident early enough. Although they were unable to stop the train, they had time to use the loudspeaker to warn people in the station, around the platform, and even beyond – alerting pedestrians, passers-by and those waiting at tram stops. Responding to the urgent call, people scattered in all directions of the wind tunnel. Ultimately, the train came to a halt 14 metres beyond the glass wall of the station, accompanied by a loud noise.

Upon arriving at the scene, the police detained and arrested several people, including the engineman, the shunter, and the guard. An exhaustive investigation, which ended on 31 January 1963, established the responsibility of two people. The shunter had failed to instruct the guard to connect the train to the locomotive and had failed to check that they were properly connected. And, as it turned out, he did not even carry out a brake test, which he should have done. The other culprit was the guard who failed to check that the locomotive and the train were properly coupled. They were sentenced to one year's imprisonment each but ultimately did not have to serve any prison time because of the 1963 amnesty provision. Retribution was not spared, however, as both workers were dismissed from MÁV (Hungarian State Railways company) with immediate effect.

(Borítókép: Magyar Rendőr - Fortepan)