The whole city, the whole country, in fact, was eager with anticipation as it prepared for the millennial celebrations, marking 1,000 years since Hungarians conquered this part of the Carpathian Basin. Airships, towering palaces, a fountain in brilliant colours, an entire mock village and any number of events awaited visitors to the City Park as the Emperor himself opened the show, this week in May 1896.

Today, it’s perfectly normal for a street or an entire park to double up as an exhibition space – the Venice Biennale, for example. In similar vein, visitors in 1896 wandered between walkways, ornamental gardens, sparkling pavilions and fountains while airships soared above.

Nearly 240 pavilions showcased the millennial heritage of Hungary’s

history, culture and industry, representing its brilliance and its bright

future. And these pavilions were not like newsstands – many were actual

buildings, decorated with towers, domes and lace patterns, built in Gothic,

Renaissance and Baroque styles.

All were created from temporary materials, of

course – although Vajdahunyad Castle proved such a success, it was recreated

in permanent form a few years later.

Although Népliget, Margaret Island and the area around Kopaszi-gát emerged as possible venues, the organisers kept with Városliget, the City Park being the cheapest solution. They also had to chop down 800 trees to make room for the exhibition, eliciting negative stories in the local press.

In 1885, the National General Exhibition was held here, the three remaining buildings – Műcsarnok (today’s Millennium House), the Industrial Hall (later the Petőfi Csarnok concert venue) and the Royal Pavilion – recycled a decade later.

Once the venue was in place, another debate began: should it be an international or national exhibition? A World’s Fair would put Hungary at the centre of Europe, but more people wanted to keep the country’s millennial celebrations strictly within the national framework.

In 1893, an architectural design competition was announced, which received 34 entries, of which four were immediately selected.

The exhibition presented the main moments of the country’s cultural development, broken down into historical epochs, through various documents, crafts, tools and works of art.

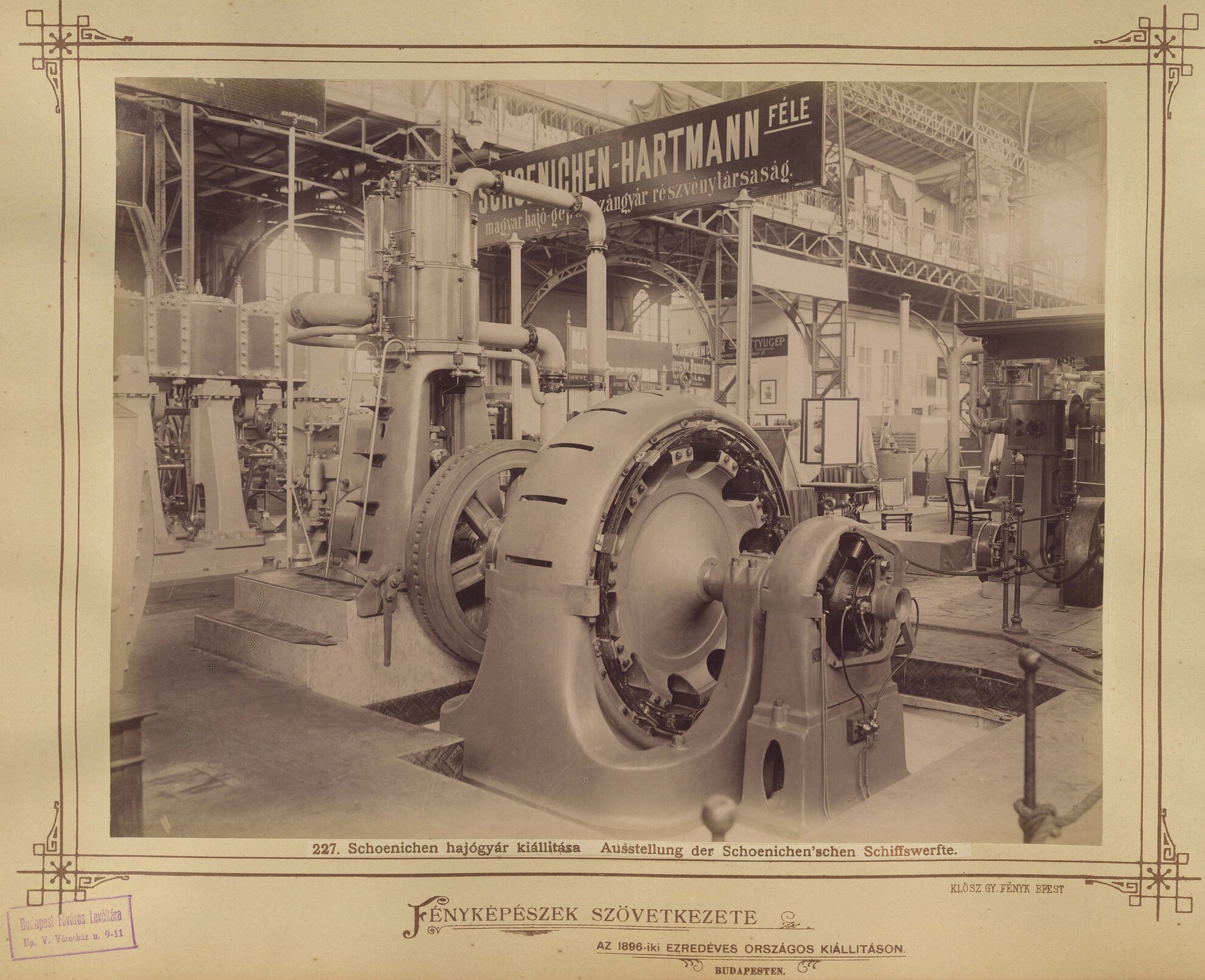

The historical exhibition was held in the wood-and-cardboard Vajdahunyad Castle, while the present, economic and industrial progress were displayed in the Industrial Hall.

During the exhibition, ships full of passengers arrived in Budapest, which was the scene of a busy social life, many sewing special clothes for the occasion. Fashion salons specifically advised everyone to sew their own clothes, avoiding the embarrassment of seeing someone else wearing the same thing.

From coal mines to factories and the army, education, forestry, viticulture and beekeeping – to name but a few of the pavilions – essentially everything was on display.

These were even made more attractive by interactive functions. Inside the Post & Telephone Pavilion, for example, you could listen to the latest cultural and political stories on the earphones, or the voice of celebrity writer Mór Jókai.

In addition, there was a strong emphasis on entertainment, so in addition to the Beer and Champagne Pavilions, the more enterprising could try the airship (although it was wrecked on a windy August day), have fun in the Ancient Buda Castle Fun Quarter or take a ride on the electric railway. Music lovers had the first opportunity to hear ragtime, not long after it broke in America.

Organisers created a serious

press campaign, founding 11 newspapers only dealing with the exhibition. The

city was full of posters, special stamps, postcards and colourful, eye-catching

publications.

All it needed was Emperor Franz Joseph himself to open the whole

shebang on 2 May 1896.