Gerhard Richter can be considered one of Germany’s greatest living artists, someone who lived through much of the turbulence of the 20th century. The 3,000 works he created are not easy to classify into different eras, his oeuvre typified by the continuous blurring of reality and appearance, capturing a moment and realising its disappearance, and the relativity of specific historical periods, their transient political and social systems. Doubt and scepticism are the result.

From East to West

He was born in Dresden in 1932 and worked within the narrow confines of Socialist Realism in the GDR until 1961, After the seminal exhibition in 1959, the Kassel documenta, he changed direction and escaped to the West, where he studied art once more. In Düsseldorf, Richter learned about contemporary art trends, creating his own distinctive visual language, both figurative and abstract, rich in colour.

Nearly 80 examples can be seen at the National Gallery. The exhibition is not in chronological order, so the artist’s announcement last year that he would retire strikes the visitor immediately. The show begins between 11 March and 5 April 2021, with 21 of his pencil drawings, abstract landscapes drawn after his decision to stop. From there, the order moves to the beginning of his career.

After

the graphic series Elbe, focus moves to the years of Richter searching for his

own style in Düsseldorf. In 1962, he explored the colourful and free world of

tabloids and illustrated magazines, resulting in Atlasa, initiated in 1969 and

now numbering more than 5,000 images, a collection of photos and newspaper

clippings that inspire the artist’s visual world, and a kind of parallel

oeuvre.

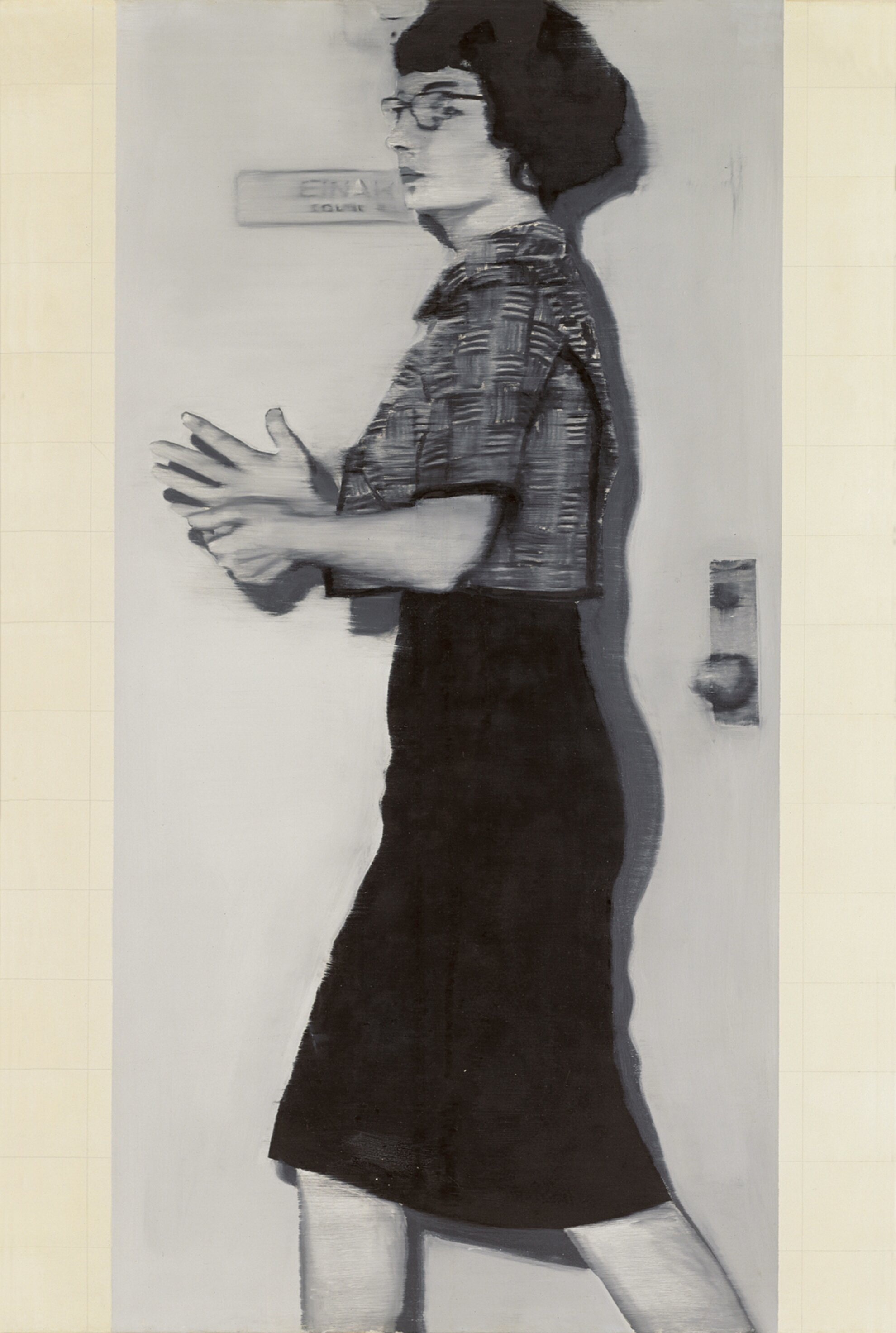

Large, grey paintings resembling blurred photos line the walls

like cut-outs. The pictures allow you to view these vague newspaper

clippings, without the story behind them, as a work of art and not as an illustration.

This is how the figure in The Secretary, say, is a strange, decorative portrait

of a woman instead of the character in a blood-curdling murder story

From here, the exhibition moves to Richter’s work for the German pavilion at the 1972 Venice Biennale, where he made 48 equal-sized portraits of scientists and artists in a book, based on randomly selected lexicon images. Although chance plays a big role in the compilation of the work, it may appear that the 48 personalities side by side are all men about whom we know no background information, so they become fully interchangeable. And this curiosity also underlines the disappointment of the post-war generation in their father figures, following an age-old pattern.

Blurred lines

An exciting example of Richter’s post-Biennale search is Annunciation after Titian, where he seeks to recreate the work of the revered painter, but the jump back in time, the moment, the impossibility of repeating the depiction, turns everything into a pinkish-brown mist.

The next room is lined with thought-provoking reflections on art history. You gain insight into the world of Richter’s family portraits, which are, of course, vastly different from the world of classic portraits. Instead of the figures appearing in their fullness, in their Sunday best, here you can see the artist’s son as a little boy, still eating, with leftovers to one side.

His wife Ingres appears while bathing, vaguely alone, in an intimate situation. In a photo-realistic portrait of her daughter from her first marriage, Betty is almost alarming, her facial expression seems alluring yet lifeless.

Landscapes also occupy an important place in Richter’s oeuvre. His cityscapes, painted from original photographs and aerial images, may evoke the bombings of his home town of Dresden, while his other landscapes evoke the world of Caspar David Friedrich, Germany’s great Romantic painter from the early 1800s, his low horizons and strange perspectives.

These are not beautiful landscapes in the traditional sense, as they often show their immediate surroundings. In the next room, Richter’s abstract works allow the viewer to piece together the inimitable system of nature in the mixture of colours and shapes.

Here, too, are elements of Richter’s iconic series Grey, a grey painting in which he transforms the basic colours of blue, yellow and red, into a single grey surface with highly expressive brushstrokes.

This way up

As a funny aside, this work was hung the wrong way for years at the German museum exhibiting it, before Richter indicated the problem in the guestbook when he visited.

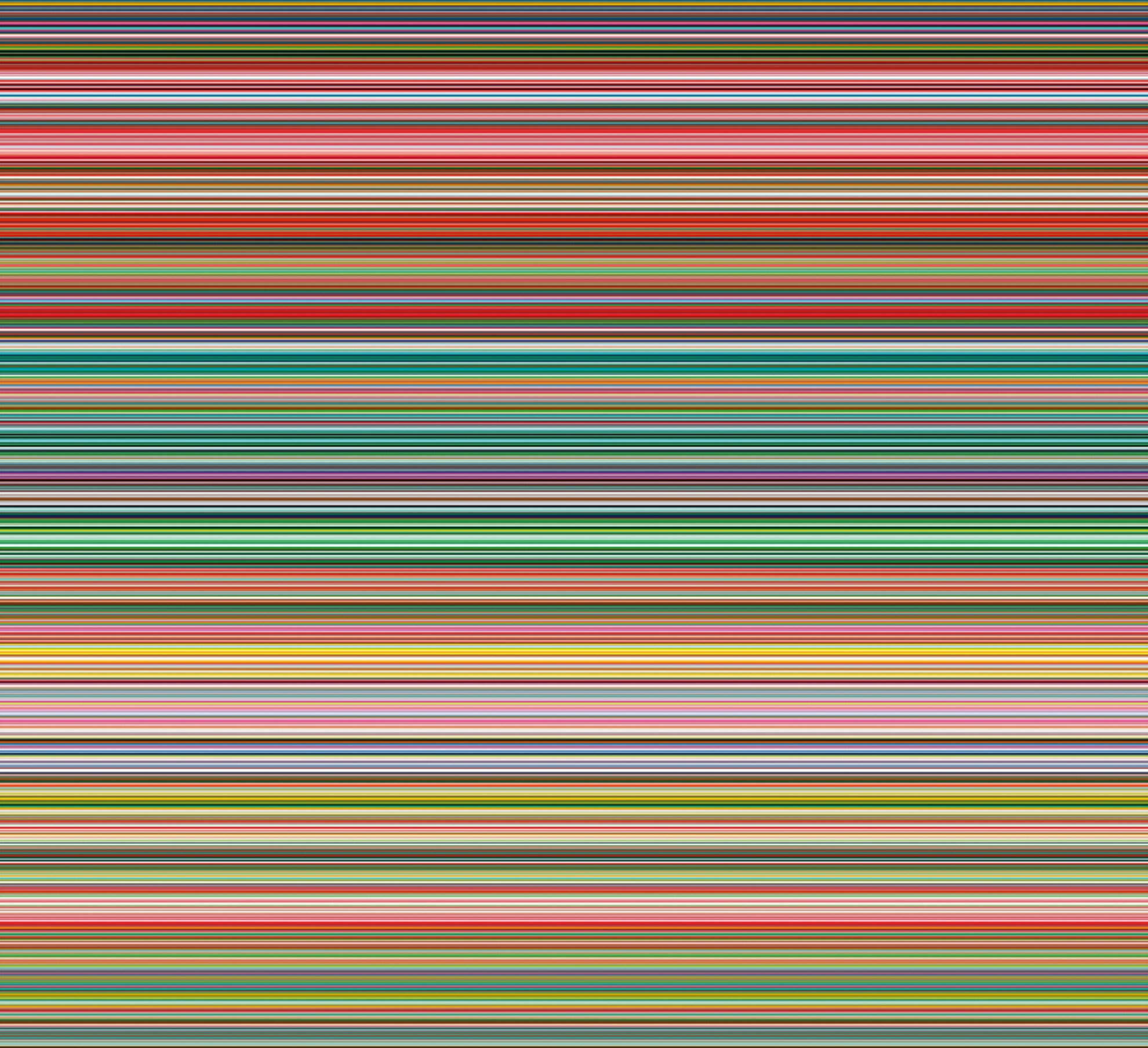

Opposite two huge, wonderfully colourful abstract works, Richter’s Strip comprises printed, coloured stripes blurring the distance between the work and the recipient – you suddenly feel like the painting is starting to draw you in, making it difficult to distinguish its space from that of the exhibition.

Here you come to the last room in the exhibition, where the arrangement

of the exhibits fully reflects Richter’s ideas. In the Grey Mirror, photos of a

Sonderkommando and the colourful canvases of the Birkenau concentration camp come into view. In

the greyness, you may reflect on the past and your own presence.

The

starting point for the Birkenau series was a photo of a special unit involved

in the genocide in the death camps, displayed by Richter on his large-scale

canvases, and then, using his trowel, to form new layers to finally make the

sketch disappear.

A catalogue and award-winning documentary are presented in English and Hungarian, allowing the visitor to plunge deeper into the special world of Gerhard Richter. The exhibition runs until 14 November.

Tickets & information

Gerhard Richter: Truth in Semblance

Hungarian National Gallery

1014 Budapest, Szent György tér 2, building A

Opening hours: Tue-Sun 10am-6pm

Buy tickets here