Ask any Hungarian about great architects, Miklós Ybl, Imre Steindl

or Ödön Lechner and they will wax lyrical about the Opera House, Parliament and the Museum of Applied Arts.

As for József Hild, well,

there’s the Basilica, and... Those au fait with local architectural history

might cite the villas of Budakeszi út, and the Csendilla and Hild villas. As

for the Karczag villa, it seems to be on the point of collapse – in 2020, there

were news of its renovation, but since then, silence.

In any case, private residential buildings seems to have been Hild’s stock-in-trade. So much so, in fact, that he enriched Hungary with nearly 900. In addition to St Stephen’s Basilica, Esztergom Basilica and Eger Cathedral also bear traces of his hand – he was one of the busiest architects of his day. This is evidenced not only by his buildings, but also by the fact that he brought at least 100 fellow architects into his guild.

However, this huge company did not mean that Hild only took on major work: he was engaged in floor extensions and alterations, the same as he designed villas and residential buildings. He was a real entrepreneur, with a strong business sense in addition to his artistic instincts. It is not even out of the question that he sought a kind of monopoly in Pest, as you’ll see his buildings everywhere, even if you don’t know they’re his.

His popularity and business acumen are no coincidence: the Hilds were

mostly engaged in construction, Much of 19th-century architecture can be linked

to them. It was József Hild’s father, János Hild, who prepared the first town

planning plan for Pest, and the more famous Hild was there on building sites beside his father at a very young age.

Here he learned the mysteries of construction and architecture, which, like his contemporaries, he deepened at the Vienna Academy of Arts, complemented by the obligatory trip to Italy. Walking the streets and squares of Rome, Milan and Florence, he became acquainted with Renaissance architecture, its structural solutions and the modesty of the early Christian columned churches, which fascinated him so much that he used the simplicity of the Classicist style for much of his life.

After his studies, he also worked in Vienna and Eisenstadt, as the court architect of the Esterházys. He returned to Pest after the death of his father to continue the family business, although he had not yet acquired his master's degree. In view of the circumstances, the guild masters required him to spend his practical time with a Pest master who was none other than Mihály Pollack, of National Museum fame.

József Hild submitted an application for a master’s degree in 1817, but due to his abundant work he was never able to perform his master’s duties, so he only received the title of master builder in 1844, when he applied to be dismissed from his current post.

The great flood of Pest in 1838 covered the lower parts of the centre, wreaking havoc. Several buildings collapsed, and reconstruction reshaped the cityscape. József Hild played a significant role and most of his houses were built during this period. The Reformed Church on Kálvin tér, for example, was restored and the columned foyer created according to his design.

His buildings were always people-centred and functional, everything composed in the name of utility. He did not consider superfluous glaze important, and only sought monumentality in the design of church buildings.

Utilisation and practicality can be observed where residential buildings are concerned, as he aimed to create the most suitable type of house for the burgeoning population. The balcony-lined residential houses so typical of inner Pest are his doing, as well as mansions along Széchenyi István tér, although none of these remain today.

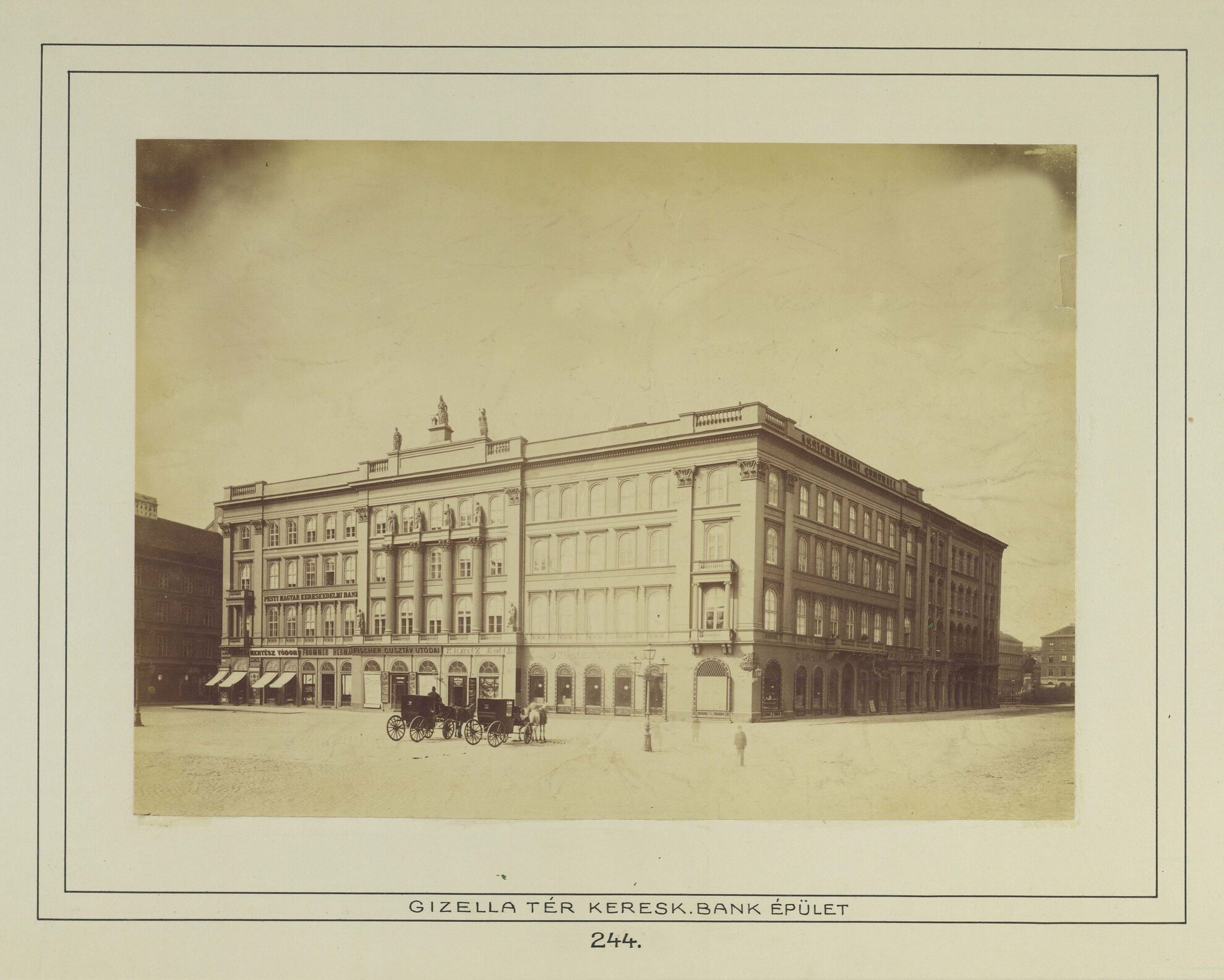

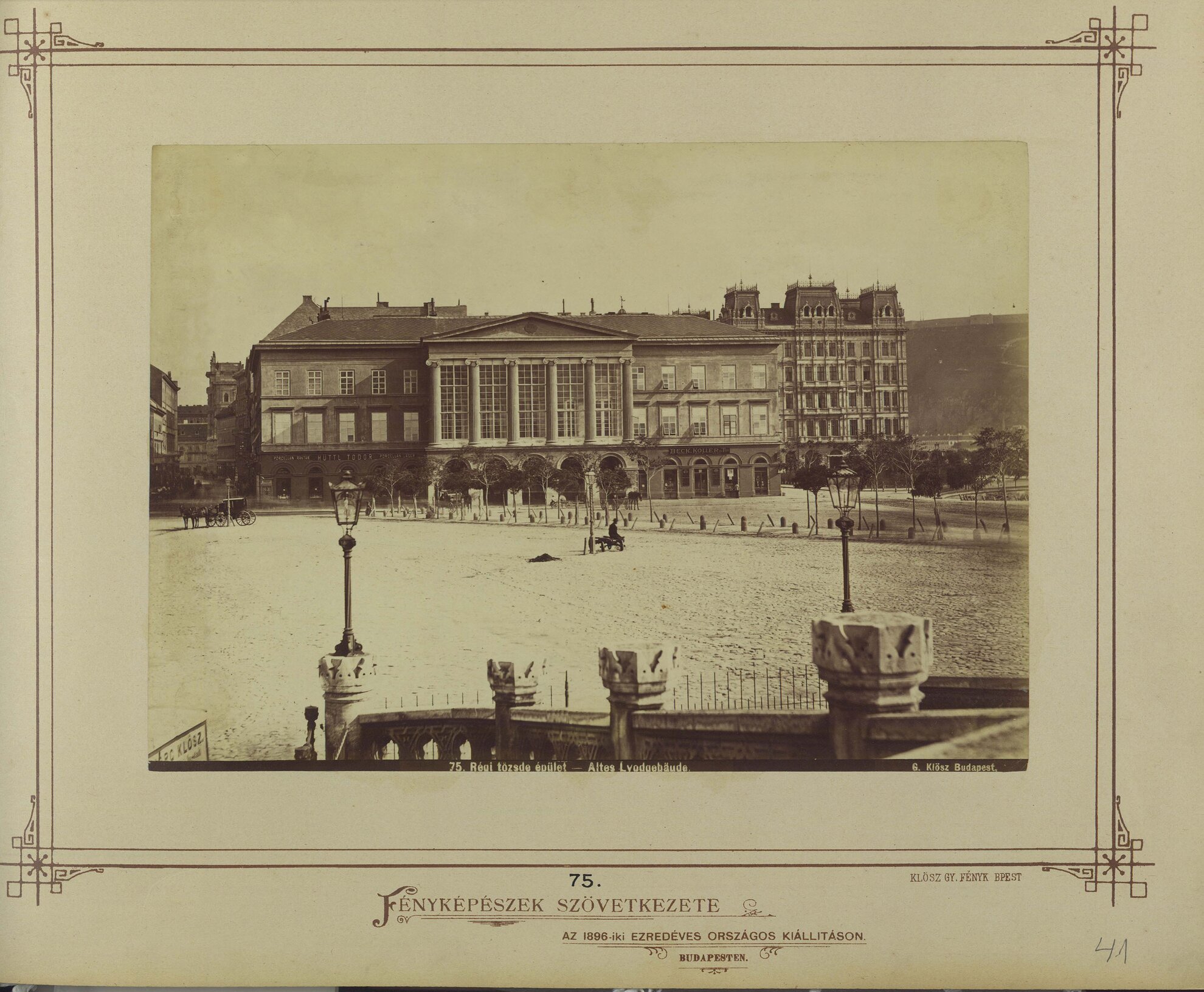

The number of buildings he built in Pest exceeds 300, although many were

destroyed or damaged beyond repair during the war. Such was Lloyd’s Palace, commissioned

by the Pest Chamber of Commerce, once the most beautiful Classicist palace in

the capital. Only its roof had burned down and its structure was not damaged,

so it could have been saved. Eventually, a single column remained, which stands

in the courtyard of the Kiscelli Museum in Óbuda.

As with all large-scale

investments, there were opponents: many complained that much of the construction was too ornate, strange considering Hild was

known for avoiding over-decoration.

We know relatively little about the country’s busiest architect, leaving only his buildings to us, but not his opinions or personality. The architect, who also designed the Fácán Inn in Zugliget, Gerbeaud on Vörösmarty tér and, of course, St Stephen’s Basilica, lived in modest conditions in his apartment in Lipótváros until the end of his life. He rarely showed up for gatherings and did not take advantage of his position but his exemplary work gained a significant following.

He was one of the prominent figures of Classicism, who wasn't afraid to design a silk factory or barracks, and whose many buildings define the image of Pest today – even if you're not always aware that you're standing in front of a Hild building.