Here’s the thing about bio wines. They’re hard to make. With conventional wines,

explains Jean-Julien, there’s a lot of forgiveness in the process. Once the

initial grape juice is fermented, there are chemicals, sweeteners,

preservatives and additives like wood chips for flavour, which can be supplemented to

save an unremarkable vintage.

When you want to produce wine that tastes good just as fermented grapes, though, that’s

when the hard work comes into play. “It’s about having the best grapes

possible,” says Jean-Julien. “The less you do at the end of the process, the

more you have to do before.”

He points to an infographic sitting on one of the tables.

It’s in Slovak, but it’s clear in its message. On the one end, we see

conventional, store-bought wines, with a list of all the possible additives

which can be inserted into the wine to improve reception. It’s like looking

at a bread label trying to find where it says 'flour'.

Moving across the

sliding scale, through the stricter bio categories, we see the list of

ingredients simplify, until we’re left with one: grapes. “They’re not designed

to be delicious,” says Jean-Julien of these natural wines. “They’re designed to

truly represent one guy in one place, making wine. They have a special taste.”

Jean-Julien’s shop opened in March, just in time for

coronavirus regulations to shut major operations down. He shows me photos

of the space when he bought it – a toilet and shower protrude from one wall,

and piles of rubbish and dusty old bricks against a backdrop of cracked

plaster. The comfortable, inviting space we see today is a testament to the

effort which went into revitalising it.

“This place was a tyre shop once,”

says Jean-Julien, “and you see these old windows?” They’re in the middle of one

wall, bricked over. Those used to be for a gentlemen’s club… with girls in the

windows”. Now one wall displays a variety of domestic and international wines,

and the other is beautiful exposed brick reminiscent of ancient Roman construction.

An upper gallery provides a view of the bar, kitchen and downstairs seating

area. In one corner, a plush couch is set up with reading material on Hungarian

cooking, and wine production.

Jean-Julien has a long history in wine, but he’s always been drawn to Hungary. “I studied in Burgundy,” he said, “and I ran a small shop in Paris for 13 years. I came to Budapest 15 or 16 years ago and fell in love, and I tried importing Hungarian wines into my Paris shop. It was a good excuse to keep coming to Budapest”. Finally the call of Hungary became too great, and Jean-Julien moved here for good.

“Only a few places are selling these natural wines,” he

explains. “The people who come here are interested in trying something new.”

And Hungary is a great place for natural wine producers to set up shop, as the

volcanic soil makes Hungary prime real estate for vineyards.

Jean-Julien takes

us through a brief history of Hungarian wine production in the recent past:

during the Communist years, the régime was focused on mass agriculture, and the

soil suffered. “It’s taken a lot of time to get the earth back,” says Jean-Julien.

He refers to one Balaton-based producer, a young winemaker named István Bence.

“He was already using organic methods, but still with a couple extra preservatives added at the end. Now he’s producing 100% natural wines, probably the best on

the Hungarian market right now.”

As a demonstration of natural techniques, sans filtration, Jean-Julien lifts a bottle of Strekov Créme #3. The sediment is visible at the bottom of the bottle. “This is not a sparkling wine,” he adds, “but with the sparkling wines, you have to be vigilant. There is a lot more pressure in these bottles than a regular bottle of champagne. If you don’t want a Jackson Pollock across your living room, you have to open these with care!”

We open a bottle of 2018 Ponzichter. It’s a Hungarian wine, grown in the Sopron area known for its Germanic roots, where residents planted beans among the vines to keep the soil healthy. The taste is straight to the point: wine, nothing more, nothing less. It’s strong, undiluted, powerful, but smooth. “We’re going for drinkability,” says Jean-Julien. As the wine swirls in the glass, he adds, “People ask me what do I recommend… Everything! It’s up to you – you’re going to drink it, not me. It’s up to your mood, because there is a wine for every part of the day”.

For the moment, it’s impossible for Jean-Julien to lead tasting sessions, which are really necessary for getting a deeper understanding of these wines. But when the restrictions are eased, he hopes to get started again. His Keddi Rendez-Vous nights include two reds and two whites – and a food plate – for a fixed price of 3,500 forints. “Our goal is to introduce people to new wines,” he says. Along with the wines, the kitchen also produces organic food, mostly from local producers. These are available presently via Wolt.

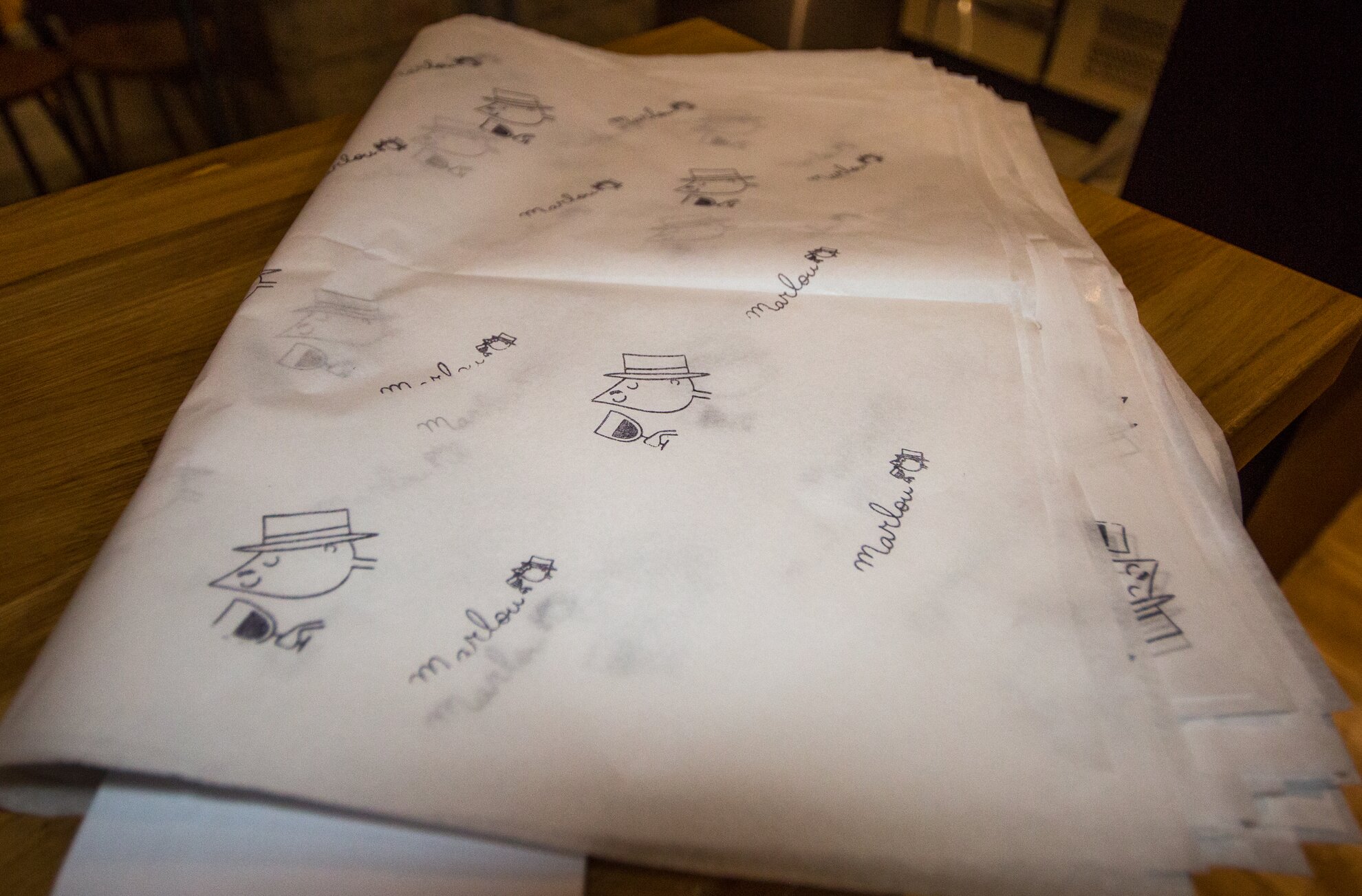

The name Marlou itself is a French slang term, which once meant a sort of pimp – now, it means someone responsible for something unexpected, which is exactly what we experience when trying the wines on Jean-Julien’s shelves. Still, he chuckles over the association, harking back to the girls who once sat in the windows of the gentleman’s club here. “I feel, in a way, like I am the pimp for these wines!” he says.

There are bottles here from Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Austria, Germany, France, Italy… the options are numerous, and their tastes are exquisite. For the wine enthusiast, on any level, Marlou is somewhere worth sampling.

Marlou

District VI. Lázár utca 16

Current opening hours: Mon-Sat 10.30am-7pm