Stalwart haunts of Budapest at the turn of the century and between the two wars were several restaurants, pubs, cafés and luxury hotels. One such was the Mátyás Pince, founded in 1904. ‘Mátyás’ himself was, in fact, Mátyás Baldauf, born in the 1970s in Borostyánkő, now Austria. He started working as a teenager, waiting tables in small communities, then Graz, then Vienna, before coming to Budapest with all his professional experience shortly before the turn of the century.

After working shifts at the Zöldfa in Krisztinaváros, he became manager of one of the city’s downtown institutions, the Kis Piszkos Söröző, the 'Dirty Little Pub'. It was a typical restaurant of the day, part pub, part café, with a decent variety of beers, freshly baked goods and great frankfurters. However, these were not the only attractions of the Kis Piszkos Söröző for Baldauf – it was here that he met Teréz Antunovics, one of its waitresses, whom he married in 1900, and whom the guests later referred to as Tercsi.

As Budapest developed rapidly at the turn of the century, the old city centre was rebuilt in many places. Baldauf and new bride rented one of the cellars in a new tenement house at the Pest end of what is now Elizabeth Bridge, to set up their own restaurant. The Mátyás Pince was opened in 1904 on Eskü tér, today’s Március 15. tér. An invitation for the opening event survives to this day:

Dear Guests!

I have the honour to inform you that on the 30th of the current month, a Saturday, at Eskű tér 6 (corner of Duna utcza s Kéményseprő-utcza) in Budapest, IV. District, I will open a wine and beer house named ‘MÁTYÁS PINCE’. As a once long-term manager at the renowned SCHOLCZ-BITTRICH [the Kis Piszkos Söröző], I hope to be able to meet your expectations based on my fruitful experience there. I took care of the fine beer and truly decent wines.

I won’t have a full kitchen here, but cold plates and a wide selection of favourite pub dishes and delicacies will be available.

Respectfully looking forward to your visits in number,

Mátyás Baldauf

As the text illustrates, the Mátyás Pince was initially more similar in range to the Kis Piszkos Söröző than to a restaurant patronised by world-famous actors and politicians 60 years later, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. The Mátyás Pince, which had only four staff when it opened, poured nine hectolitres of beer on that first day. In ten years, the turnover increased so much that the cellar of the neighbouring house was rented out – this time as a restaurant. Staff increased to 30.

The first regulars soon organised themselves around their own tables, gave themselves different names, and tried to spend as much time as possible at their new home. According to reports at the time, it was not uncommon for the tables to line up in several rows, and the hard-core members had their own personalised mugs at the Mátyás Pince. Back then, the establishment still did not have operate as a restaurant per se, but basic dishes, stews, sausages, cheese, pork knuckle, were served, and it was well known throughout Pest for having the best beer in town.

Mátyás Baldauf bought the whole tenement house in 1927, then two years later the restaurant was expanded with the Fishermen’s and Jubilee Halls. That was the year when Baldauf received the Grand Gold Medal of the National Association of Craftsmen for his work and, for the 25th anniversary of his establishment, he reduced his prices to what they were in 1904. In the period between the two wars, many well-known politicians, public figures and artists visited the Mátyás Pince, including writers Gyula Krúdy, Frigyes Karinthy and Zsigmond Móricz.

After Baldauf’s death in 1937, his wife and two sons took control of the business. The Second World War created far worse havoc than the First, with many of the cellars badly damaged during the fighting. Nevertheless, the very day after the end of the Siege, they were open. True, they only functioned as a communal kitchen and sold dishes for food stamps.

For a year or two after the war, it seemed possible to resurrect the Mátyás Pince, but the year 1949 proved to be decisive. The restaurant was nationalised under Communism at the end of December, and even the house was taken away from the family.

That it still survived at all is due to another major dynasty in the hospitality trade. Endre Papp’s family had been innkeepers for many generations but they, too, were dispossessed of their restaurant in Kispest, the Halásztanya, designed by famed Art Nouveau architect Károly Kós.

However, Papp’s knowledge did not go to waste despite nationalisation as he was appointed head of the moribund Mátyás Pince. The creation of a restaurant kitchen here is also linked to him.

Legend has it that in the grim 1950s, Papp also made a certain brassói aprópecsenye here, the revered Brasov pork fry-up, using scraps from 1,071 pork tails at the time of a meat shortage – although this was later refuted by award-winning contemporary food writer András Cserna-Szabó in his book Erdélyi lakoma újratöltve (‘Transylvanian Feasts Revisited’), as the recipe appeared in an edition of Ujság in 1942.

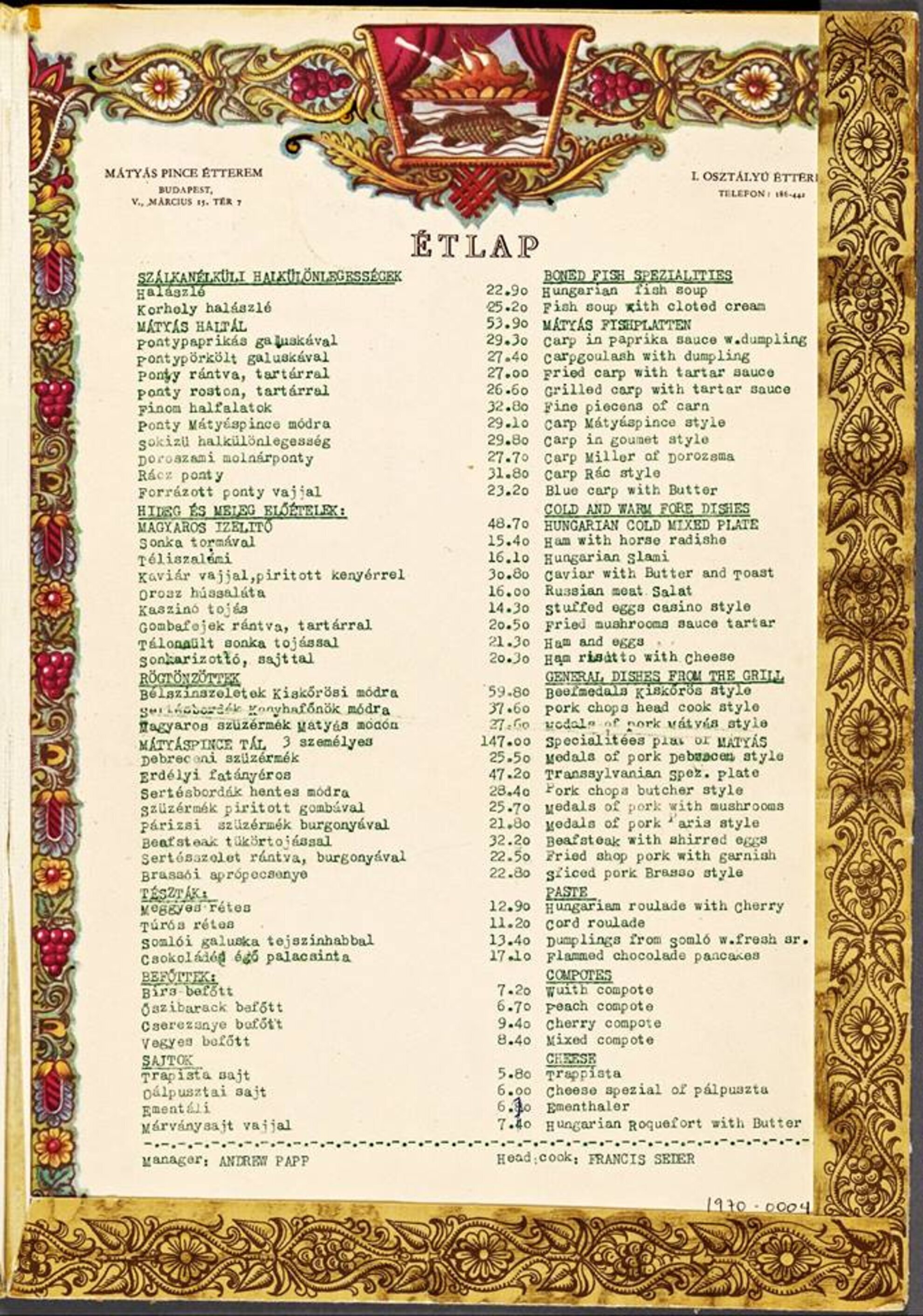

What cannot be disputed is that under the stewardship of Endre Papp, the Mátyás Pince survived the bleak 1950s, and in the subsequent thaw, when tourism also started, the restaurant began welcoming foreigners. Papp served them relatively light Hungarian cuisine, modern for the time and created according to his own recipes.

In the 1960s, it was not only the political elite who discovered Baldauf’s former pub, but also the celebrities who visited Budapest. Papp would welcome illustrious guests such as Grace Kelly, Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Alain Delon, Liv Ullman and Yehudi Menuhin.

While Elizabeth Bridge was being built in 1964, the restaurant was forced to close, but they used the opportunity to carry out timely internal alterations. In 1971, it finally reopened in complete splendour. A musical element had also evolved in the mid-1960s. A member of one of Hungary’s oldest traditional music dynasties, Sándor Lakatos Déki Sr, played for guests in the evenings, a role his son later inherited. The Mátyás Pince became synonymous with Gypsy music, folk songs and operetta.

From the Papp era until 2008, the Mátyás Pince started to decline significantly. After the fall of Communism 1989, it became a typical overpriced tourist trap. In 2008, new owners took it over, and sought to restore its reputation. Closed for renovation in January 2020, it hopes to reopen before too long, and continue on its 116-year odyssey.