On this day in 1953, arguably the most famous match in football history took place in London between triumphant visitors Hungary and hosts England. The outcome was the iconic score of 6-3 but the consequences of what happened on this misty November afternoon 67 years ago were more profound, enshrining in legend a Hungarian team considered one of the finest to step onto the field of play.

Fog and myth surround the momentous events of 25 November 1953. On this day at England’s national stadium of Wembley, Hungary’s football team not only beat the hosts 6-3, the Magyars gave the game’s pioneers a lesson in football. It is known as the Match of the Century.

Although

all members of what Hungarians call their Golden Team, the aranycsapat, have passed away, in circumstances ranging from a

strange suicide in a Barcelona hospital to a grand state funeral at St

Stephen’s Basilica in Budapest, the stature of their achievement lives

long.

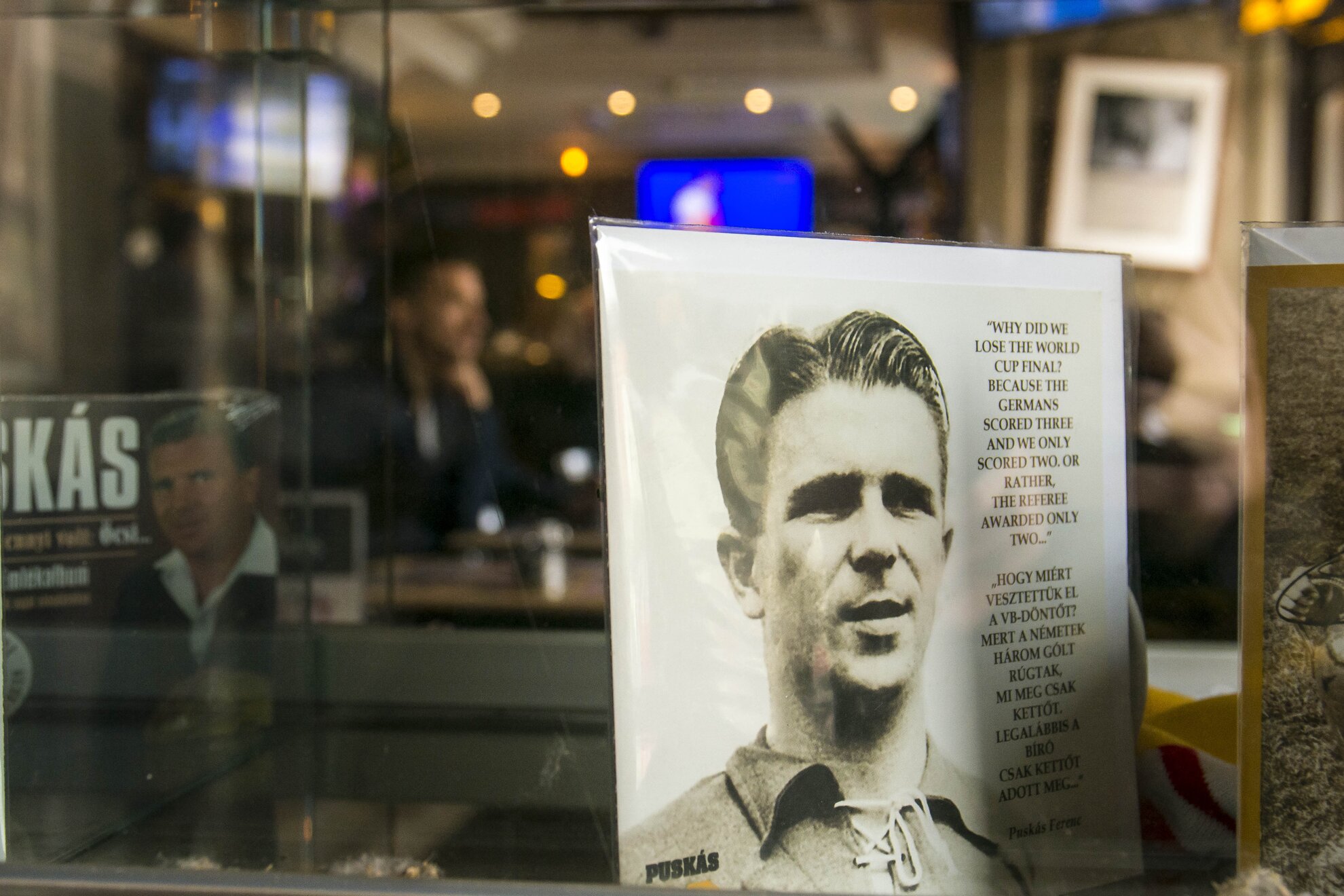

Star player Ferenc Puskás remains an iconic figure decades later, his

image sold on T-shirts in souvenir shops, his name used for a sports bar in Óbuda

where a statue and square have been created in his honour.

For generations, the game has linked the two opponents on the football field that day. Upon his arrival here, incoming UK Ambassador to Hungary, Mr Paul Fox, presented a video in which he introduced himself as a Londoner and a fan of Tottenham Hotspur and England, humorously alluding to the famous match.

Personal history

In fact, Mr Fox has deeper personal ties to the match in question. As he told We Love Budapest, “I heard a lot about the Match of the Century from my father who was at the game in Wembley Stadium in 1953. He had a great admiration for Ferenc Puskás and Hungarian football”.

Previous ambassadors have also appreciated the significance of 1953. “In 1996 the British Embassy in Budapest obtained the rights of the match from the BBC and permission from the English FA to show the match on Hungarian television,” said Mr Fox. “Magyar TV even changed its Christmas Day programming at the last minute to make room for the match, and for the then British Ambassador to introduce it. This was the closing of a series of events organised by the British Embassy in celebration of Hungary’s millecentenary year.”

“As a result of my introductory video, Magyar Telekom, who digitalised the BBC broadcast of the game, invited me on social media to watch the match and kindly offered to colour an English goal of my choice besides the Hungarian ones,” explained Mr Fox. The reconfigured footage of the game is being screened today at 6pm on TV2.

On the Hungarian side, the original Hungarian radio commentary (‘Gól! Góóóól! Gól!) by the equally legendary György Szepesi evokes the emotion and significance of the occasion. It lent authenticity to the popular Hungarian film 6:3, avagy játszd újra Tutti (‘6:3 Play it Again Tutti’), a gentle comedy involving identity and time travel. All takes place around this very day in 1953.

Among the many myths surrounding the game, one is that a balcony in Budapest collapsed when people gathered around a radio set were celebrating one of the six goals. That probably never happened but the influence of 6-3 lives on.

This summer, on the national day of 20 August, the 75th anniversary of his debut in the legendary Hungarian team, Ferenc Puskás was celebrated with an all-singing, all-dancing musical at Budapest’s Erkel Theatre, the 6-3 game re-enacted by performers in the storied white of England and cherry red of Hungary, flying through the air on high-tension wires.

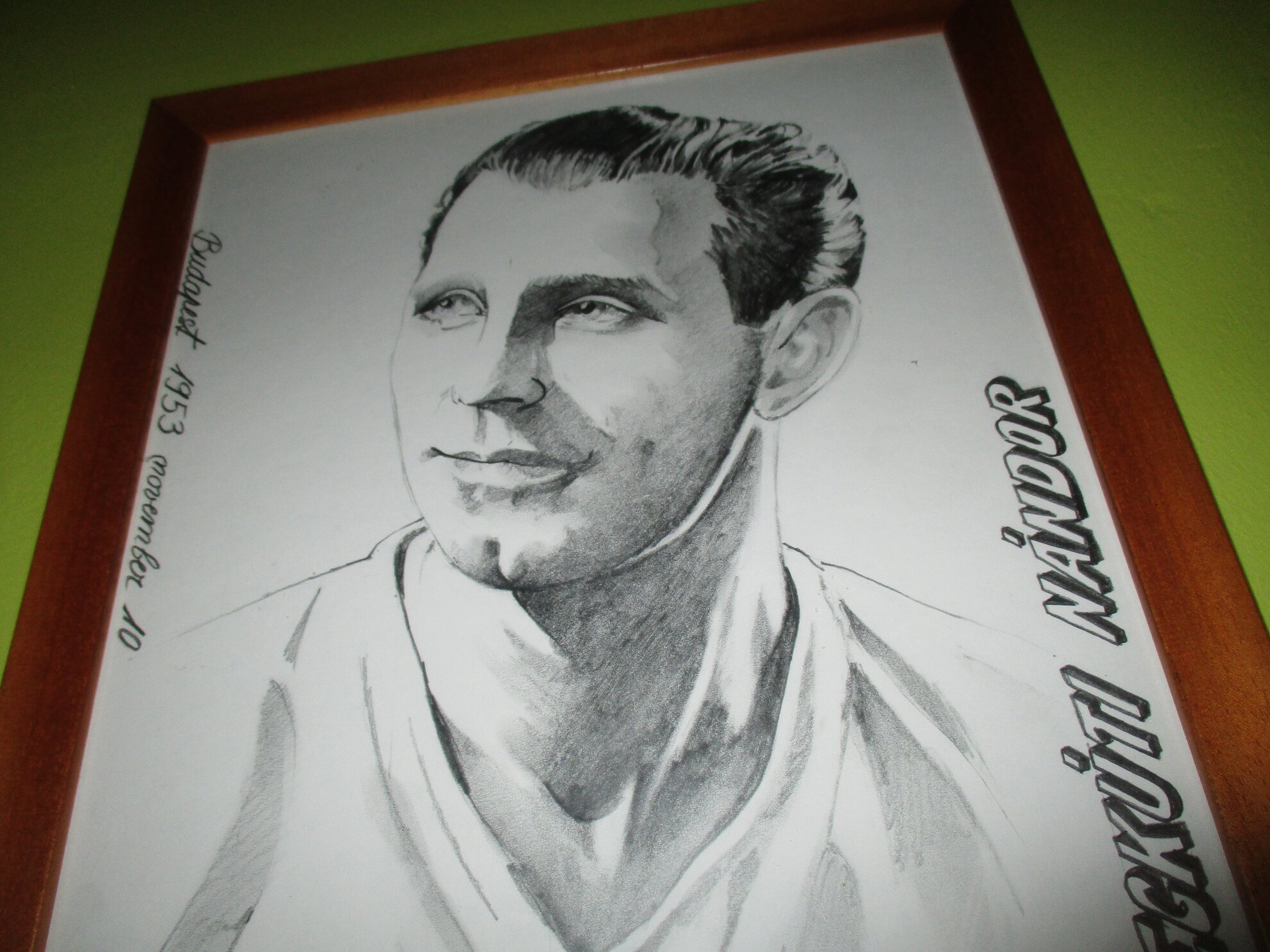

Across town, the 6:3 Borozó, a traditional Hungarian bar themed around the match, has been a permanent fixture on Lónyay utca for generations. Originally owned by the scorer of three goals that November day, Nándor Hidegkuti, the 6:3 is now run by a group of expat enthusiasts who have vowed to preserve the heritage of this revered landmark.

Although 2020 is obviously different, the shutdown of pubs and restaurants coming just before Hungary qualified for a major finals for only the second time in 40 years, the bar usually turns each anniversary into a special occasion. In 2019, the team invited Guardian football expert Jonathan Wilson to give a talk about the tactical significance of the Match of the Century.

Separating fact from myth is again an issue. For all its groundbreaking magnitude, the game had no trophy riding on it. It was a friendly international, between a Hungarian team that had not lost since 1950 and an England one thought invincible at home.

This, again, is somewhat of a myth. Up until November 1953, England had hosted continental or South-American teams 21 times, relatively few considered the first international on home soil, with Scotland, was 80 years before, in 1873. Before this game, only three others against non-British opponents had taken place at Wembley, the first in 1951.

Still, there was no doubt that this game was prestigious – and mysterious. Little was known about Hungary, hidden behind the Iron Curtain, the Stalinist era long yet to thaw, the Soviet leader given a state funeral only months before.

Hungary’s team was comprised of

players mainly based at one club, Honvéd, which represented the Hungarian Army.

Their familiarity with each other, playing together week after week instead of

every few months as national sides do, gave Hungary a clear advantage.

Ferenc Puskás

and József Bozsik, star player and captain respectively, had grown up several

houses apart in Kispest, the original name and location of the Honvéd team.

The flexible tactics deployed by Hungary, using Nándor Hidegkuti as a deep-lying forward, while England were stubbornly rooted in traditional positions, were another main factor for the victory.

Before 100,000 Wembley spectators, behatted to a man, it took Hidegkuti 45 seconds to score. He then outfoxed the static English defence, move after move after move, for the remaining 90 minutes. Centre-forwards weren’t meant to do that.

Goal #3 is the most celebrated, the Puskás dragback on 24 minutes. His later lifelong friend, England captain Billy Wright, was famously described as ‘running to the wrong fire’ as the Kispest urchin magically made the ball disappear with a lightning-quick sleight of left foot. But what created the chance was Puskás switching flanks with Zoltán Czibor. England didn’t know whom to mark.

On the radio commentary, Szepesi laughs as Puskás kisses an England player on the cheek when making his way back to the centre-circle, immortality achieved in a single split second of genius.

After their status-smashing 6-3 grand slam, the Hungarians returned home in triumph. Six months later, they would beat England 7-1 in Budapest but then lose the World Cup. It is said that the public anger that erupted around the capital was a prelude to the Hungarian Uprising of 1956. Afterwards, key players, including Puskás, defected to the West, to find global fame in Spain.

But that’s another story.