Curated by art historian and life-long skateboarder Zsolt Petrányi, The Street is not a Playground fills an attractive, first-floor space filled with natural light that floods in from the passageway separating the upscale Kempinski and Ritz-Carlton hotels opposite.

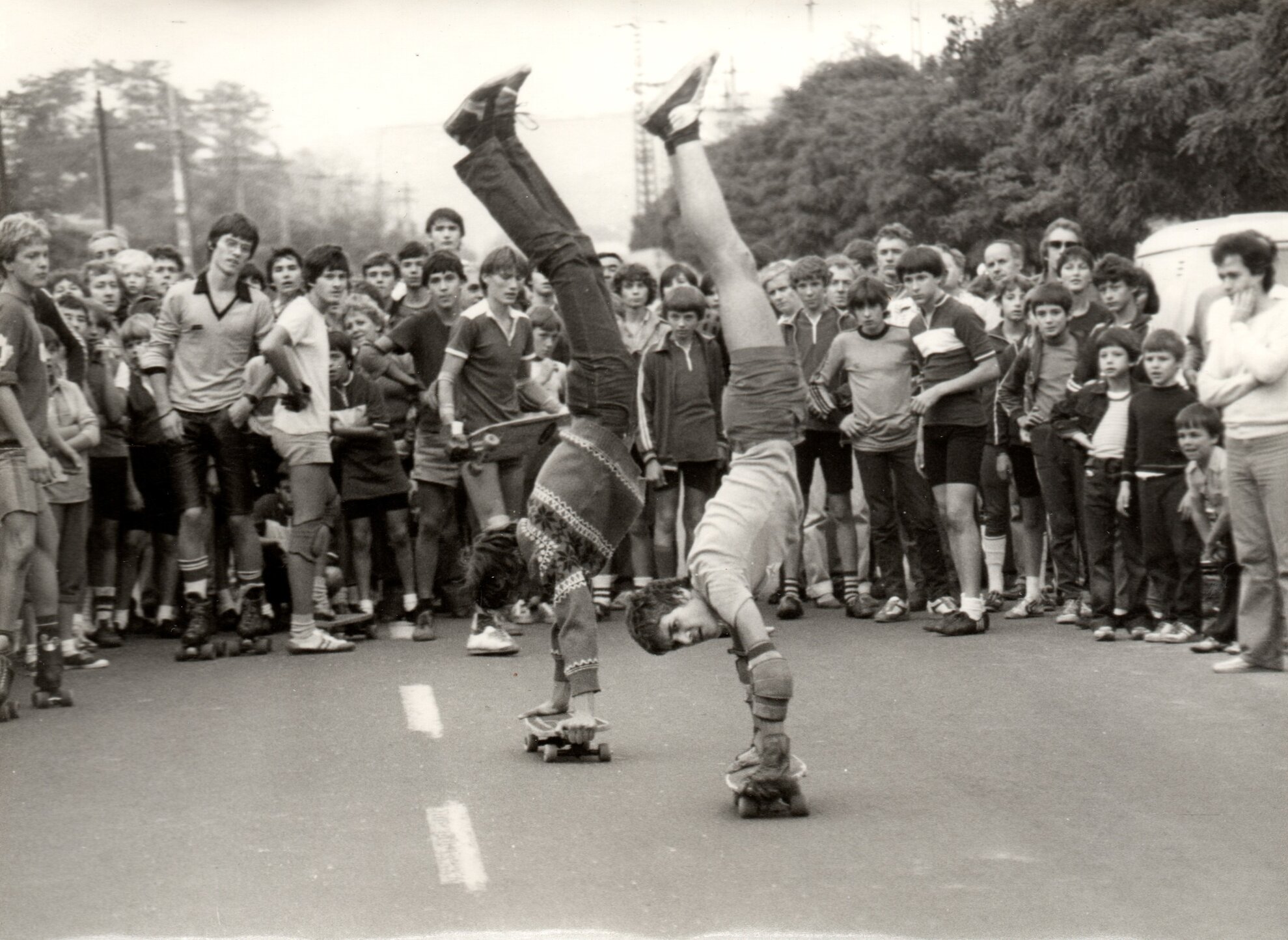

After pressing bell 7, climbing a flight of stairs and following the signs, you suddenly find yourself deep in a different time zone entirely, when skateboarding was all the rage. And, here in then Communist Hungary, this was a craze that had come from the West.

“As a curator and a cultural organiser,” Petrányi begins, “you always want to deal with a topic of potential interest to several generations. There is my own personal involvement, my wish to show the true face of a subculture so that anyone who has never skateboarded can understand it. Any young man who comes to the show and happens to be rebelling against the world, his environment and his parents by skateboarding, will be confronted with a history of parents rebelling in the same way”.

The curator’s comments are apt, in that one of the earliest exhibits is a letter his father Győző, a university professor, wrote in 1983 to a local Communist Party official (‘Dear Comrade…’) asking for permission to build a ramp in Pilis Park for young skateboarders.

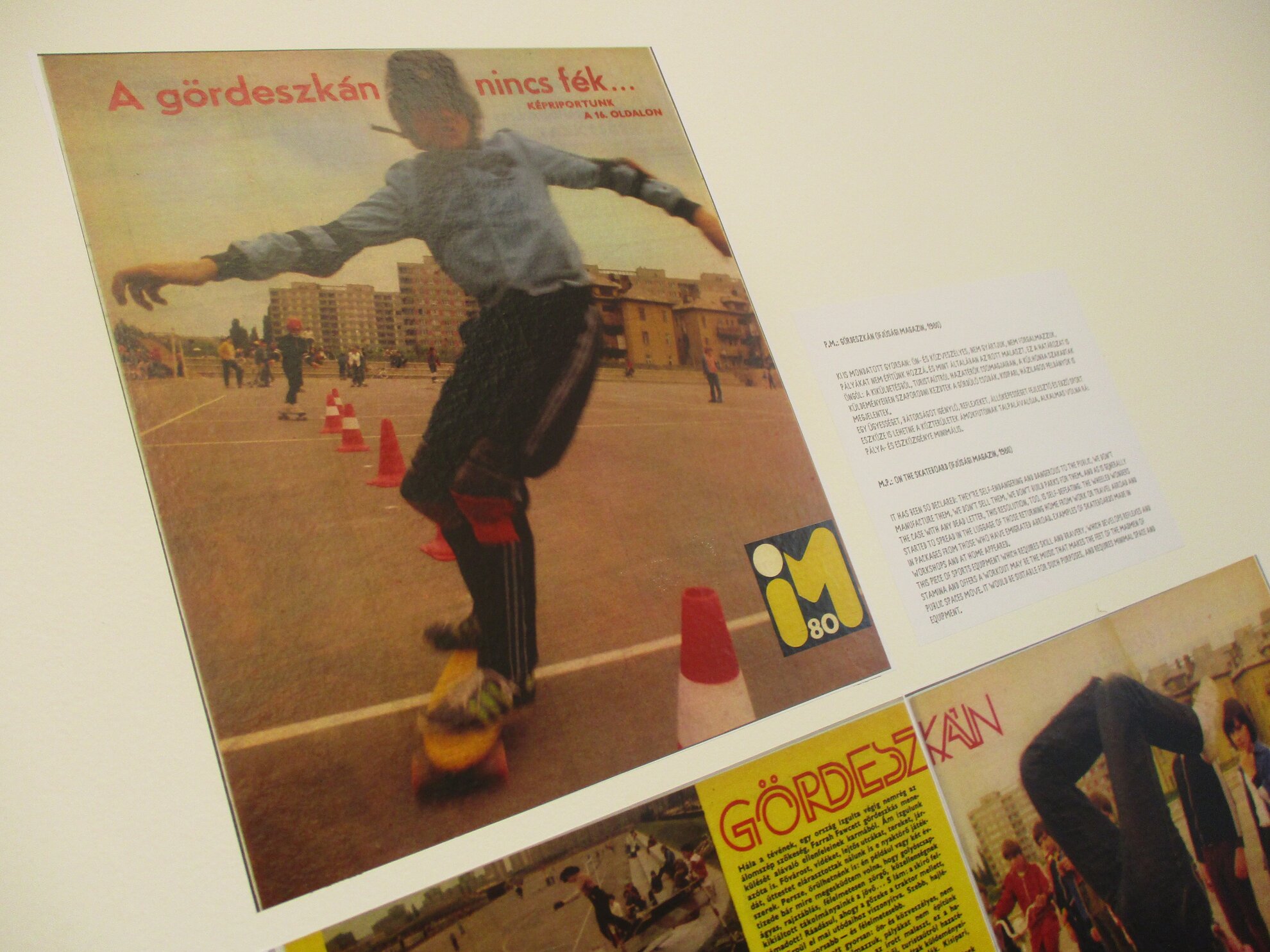

But the activity, and the documentation, date back even further. An article from Ezermester dating back to 1965 headlined Surfing on dry ground shows Communist Hungary’s remarkably early interest in the craze, not long after it had taken off in America.

Even if teenagers could not easily get their hands on the latest records by the top pop groups in the West or a pair of Levi’s, they could read about this new subculture.

“At the time,” says Petrányi, “it was presented as an opportunity for skiers to improve their balance by skateboarding in the summer. After all, you’re going down a slope and turning round at the same time. Domestic journalism immediately interpreted the phenomenon in the context of sport which, although different from the American concept, was a great help in getting many young people to get involved. In America, where it began in the 1960s and they started to build concrete ramps almost immediately, it was considered a cool street spectacle. Not with us”.

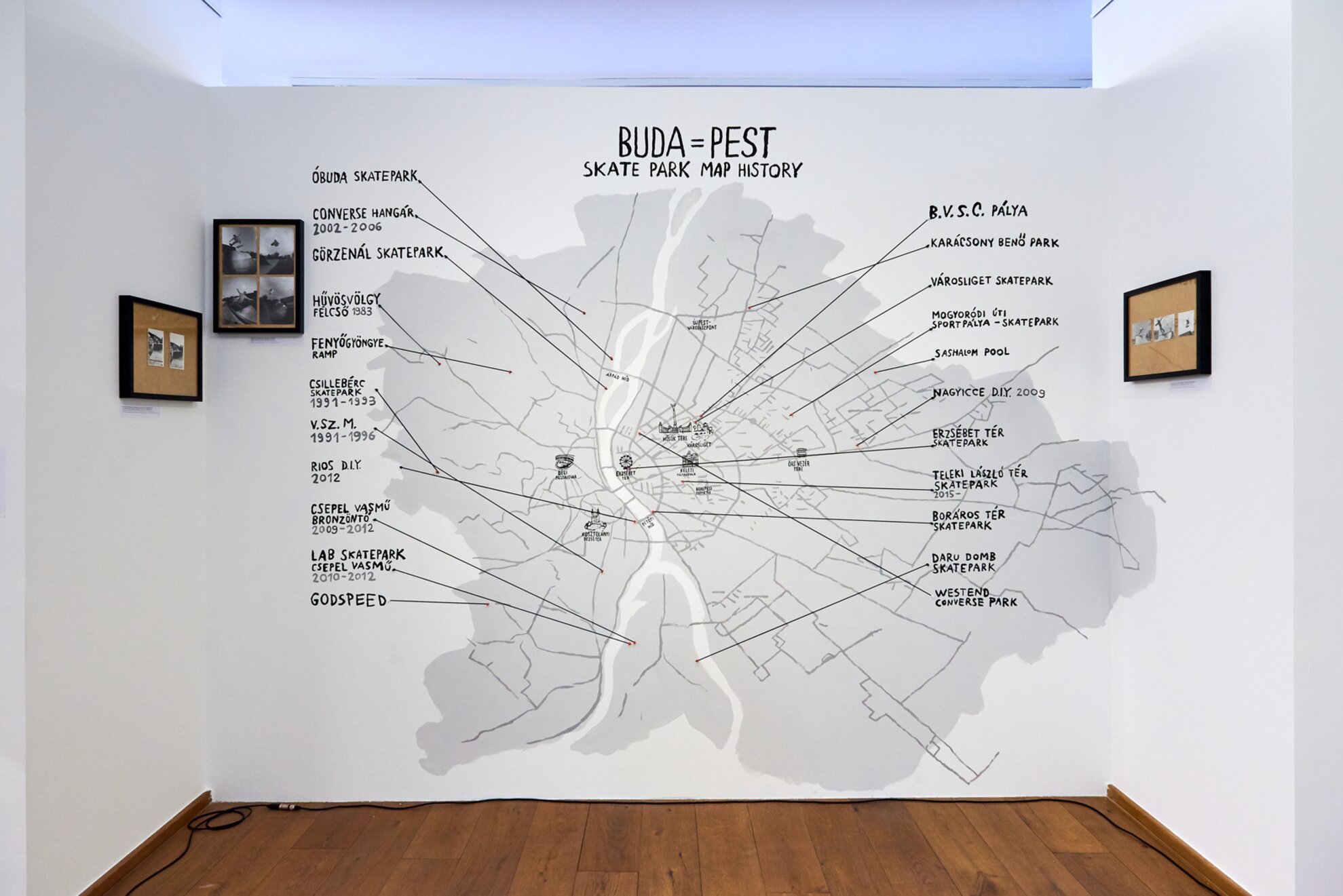

Walking around the exhibition, laid out in chronological order, perhaps the most interesting feature are the maps showing where skateboarding spots and parks have been set up around Budapest, many of them long disappeared. ‘Above the Tunnel’ is one, a somewhat risky location overlooking the Chain Bridge – a separate display of portraits honours local skateboarders no longer with us. Early sites also include City Park and the Millenáris cycle track. Heroes’ Square has been used by skate punks for decades, Erzsébet tér since the bus station was knocked down in 2002.

By the window, running along half the room, another display shows the history and development of skateboards themselves, from primitive pioneers to sleek machines perfect for fast slaloms. According to Petrányi, the move from metal and hard-plastic wheels to polyurethane ones four decades ago opened up a world of possibilities.

Look out too, for the instructional diagrams by graphic artist Attila Stark, showing you how to do the flip varial, among other tips and tricks.

With skateboarding selected as an Olympic sport at Tokyo 2020, interest has never been higher in this street activity – but for the curious visitor, this exhibition offers an insight how life was here before the Wall came down in 1989.

Admission is free.

The Street is not a Playground (Az utca nem játszótér)

Deák 17

District V. Deák Ferenc utca 17

Open: Until 14 December, Tue-Fri 10am-6pm, Sat 9am-1pm