A street map of Újlipótváros in the late 1880s shows a small grid of streets bereft of construction. Alongside, Pest is already busy and built-up. Within 20 years, Pozsonyi Avenue, the spine and shop window of Újlipótváros, was developed. Within 40, it was a refined residential district, all Modernist housing, with distinct Art Deco touches to follow.

Today the tone is quickly set as we leave Margaret Bridge, Jászai Mari Square and the regular yellow blur of trams 4 and 6 behind us. On the Danube side of the sidewalk, the Palatinus Houses date back to 1911, architectural pioneers before the rest of Pozsonyi Avenue took shape.

On the starboard side, the first corner spans 70 years of urban history. Directly under the street sign for Pozsonyi út 1, a striking plaque depicts tragic poet Miklós Radnóti, trapped behind barbed wire. We will meet this victim of war-time brutality further along in our walk. His was not the only such fate, as we will also discover.

On the facing corner, opposite a finely crafted plaque dedicated to another former resident, famed ceramist Margit Kovács, we find a fine example of the contemporary dynamism of Pozsonyi Avenue. Opened in 2016, Babka, named after a layered chocolate cake, offers quality Middle Eastern delights by day and sassy cocktails by night. Weekends see it filled with young professionals, networking over breakfast. A would-be hipster might zip past on his fold-up scooter.

The new social dynamic here is reflected in the pattern of shop windows. Here and there, the odd age-old family business – the Piccolo Sörbár, Pozsonyi Képkeretező Galéria, Nagy István Szűcsmester – survive to provide beer, picture frames and fur hats. Everywhere else is awash with estate agents and nu-skool hair stylists.

Upscale dessert bar Édesmindegy purveys sought-after cakes and puddings. Artisanal breads are prepared in full view of coffee-sipping customers at Három Tarka Macska, opened in 2017.

Standing out against the trendy tide, the Kiskakukk Restaurant represents Hungarian hospitality at its classic best, displaying its proud foundation date of 1913. At the next corner, the Pozsonyi Vendéglő is more budget-concious, with great lunchtime deals at 950 forints.

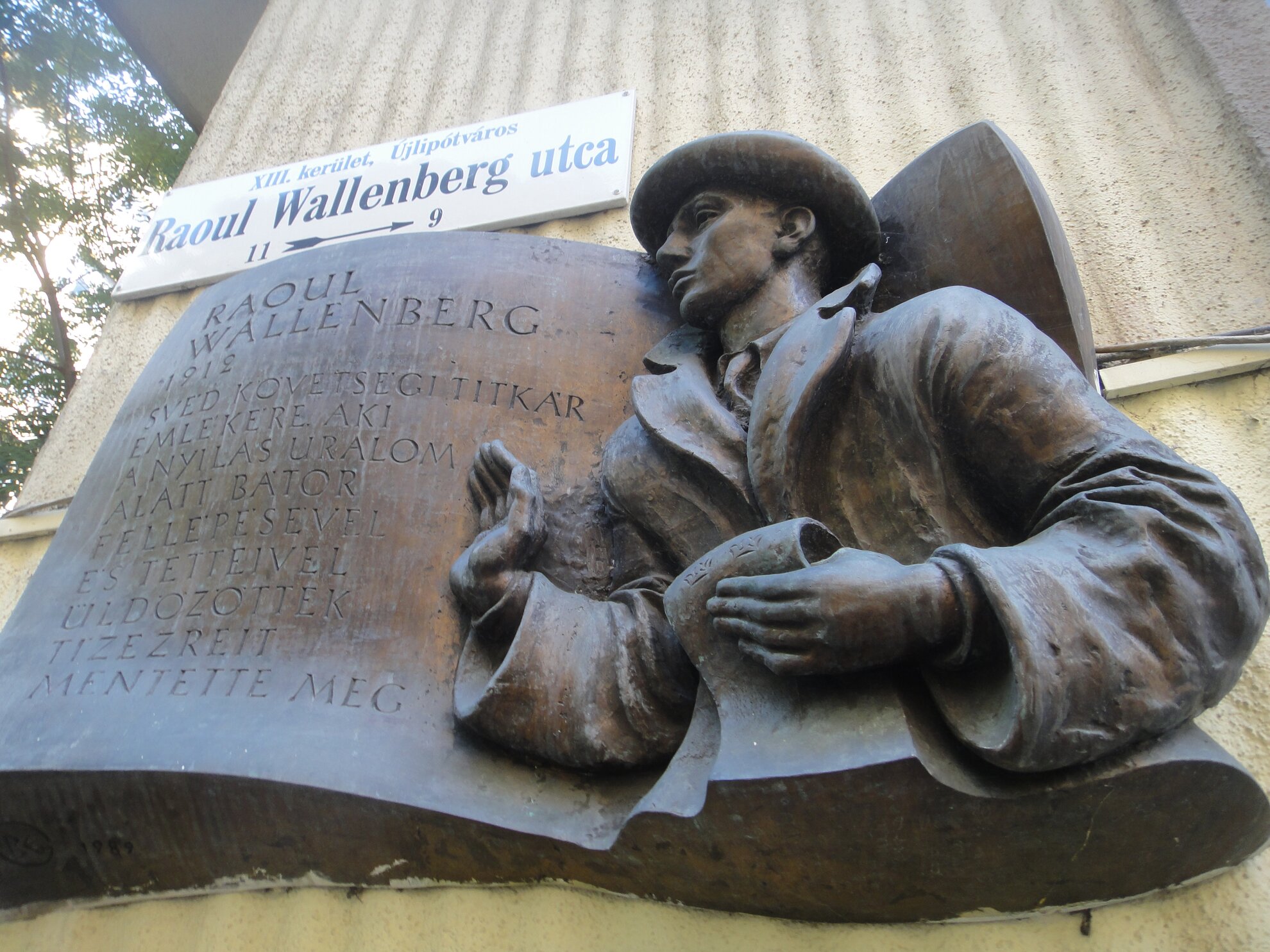

Each eatery sits at a cross-street named in honor of an unlikely hero of World War II, marked by a carved likeness and an inscription. Each suffered an appalling fate, clouded by lack of detail.

In the case of Raoul Wallenberg, heroic Swedish envoy of 1944, his lifespan is given as simply ‘1912’. Sent here by his native Sweden, Wallenberg was tasked with saving as many Jews as possible from deportation. To do so, he created safehouses under Swedish protection, indicated today as ‘Védett Ház’, as can be seen all around Újlipótváros.

At constant risk to his own life, Wallenberg ensured that more than 10,000 Jews were spared the gas chamber. As the Red Army encircled Budapest in January 1945, Wallenberg was arrested by the Soviet authorities. He is thought to have died while imprisoned in Moscow.

At the next corner, Radnóti Miklós Street, the Újlipótváros-born poet stands leaning against a railing, his trademark coat casually slung alongside, his signature running elegantly below. Sent to a forced labor camp during the war, Radnóti was shot in November 1944, though the exact date and circumstances are not known.

Within half a block, we arrive at Szent István Park. Landscaped in the late 1920s, this long stretch of fine greenery, practical and aesthetically pleasing, replaced a parquetry factory. Sealing the street’s status higher up the Monopoly board, the elegant Dunapark Café was added alongside a decade later.

Above lived award-winning actor Tamás Major and renowned dramatist Jenő Heltai, both commemorated with plaques on the building’s façade.

The 2006 restoration of Dunapark to former glories, its two-deck interior as sleek as any ocean liner, staffed cloakroom by the front door, led the way for scores more cafés to follow. Integral to their success has not only been a Pozsonyi Avenue location, but new-wave coffee, cosmopolitan snacks and signage typography that echoes the 1930s.

Opposite Dunapark stands the Sarki Fűszeres, a gourmet delicacy-cum-café with terrace. A savvy location scout could propose either venue as the backdrop for an Agatha Christie-era film shoot, and get away with it.

One final plaque here shows another victim of history, who at least survived to remain active in exile. Anna Kéthly was a Social Democrat MP until the war intervened. Successfully hiding from the Nazi authorities, she was imprisoned by the Communists, only to serve in the short-lived Hungarian government during the unsuccessful 1956 Uprising. Kéthly fled to America, lived in London, and passed away at the ripe old age of 86, in the tranquil Belgian seaside resort of Blankenberge.