On the Pest riverbank by Vigadó Square, a small concrete building serves as the ticket-sales center for ferryboats and dinner-cruise ships plying the mighty Danube from nearby docks. On one side of this building, an intriguing monument indicates high-water points from several significant floods dating back to 1876, including a major one that struck the city just in 2013; the marker for that relatively recent deluge almost reaches the roof.

However, this memorial includes no marker for the great flood of Budapest that spanned March 13-18, 1838 – because when that deluge overwhelmed Hungary’s capital, the very highest point of this riverfront building would have been deep underwater.

To get a sense of how widespread this almost-unimaginable inundation actually was, walk up from the riverbank and far into District V to find one of the most graphic memorials to the 1838 flood at Egyetem Square’s corner with Király Pál Street. This monument features a detailed map of Budapest carefully carved into pink and blue marble, with the flooded sections clearly delineated as stretching far beyond both the Buda and Pest banks, including the entirety of downtown well past the Grand Boulevard. The 1838 flood wiped out thousands of homes and left tens of thousands of city residents with nothing but their lives; 153 people were not fortunate enough to survive.

Walk further into Pest on Bródy Sándor Street into District VIII alongside the Hungarian National Museum – built in the 1840s, when the flood was still recent history – and you’ll find another small stone marker embedded into the metal fence with a carved hand pointing out the floodwater level.

And even farther into District VIII – now near Blaha Lujza Square, more than a kilometer away from the waterfront – another understated stone tablet adorns the small Szent Rókus Church, dating back to 1765 on this spot alongside Rákóczi Avenue. This shows the high-water mark of the 1838 flood at about eye-level for passersby of below-average height… but step down to the church entrance that is still at its original 18th-century street level, and the flood marker is well overhead for all but the remarkably tall.

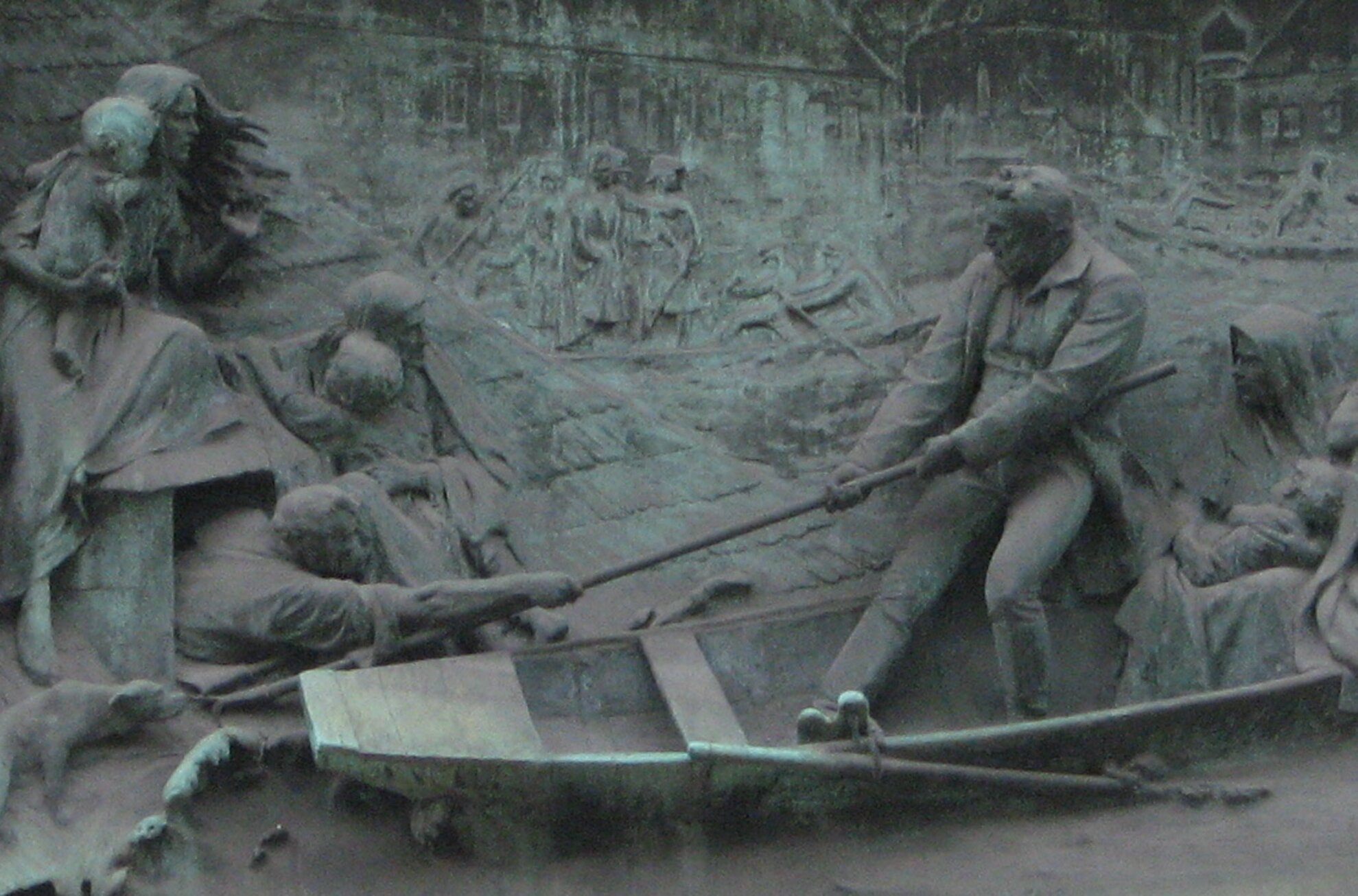

These small but solemn flood-level markers are scattered citywide in both Buda and Pest, most being so subtle that they’re usually overlooked. However, one memorial commemorating the 1838 Budapest flood is anything but understated: the huge relief sculpture on the side of Ferenciek Square’s historic Belvárosi Ferences Church, dramatically depicting the deluge with highly detailed splashing waves, submerged houses, and drenched babies all captured in metal, the vivid scene centered by a valiant man in a rowboat extending his oar to a stranded family huddled on a rooftop, complete with sopping dog.

The statue’s brave rescuer is a depiction of Baron Miklós Wesselényi, widely revered as a hero of the 1838 Budapest flood. Born to a noble family and inheriting his father’s immense physical strength, Baron Wesselényi earned national renown as a sportsman and strong swimmer long before 1838, but he he was better known as a political firebrand who risked his privileged status by attempting to shake up longstanding aristocratic systems and improve the standard of living for all Hungarians.

Baron Wesselényi was a close friend of another progressive Magyar nobleman, Count István Széchenyi (the revered benefactor behind the Chain Bridge, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and many other major national advances), and he shared Széchenyi’s passion for societal reform. As an opposition politician, Wesselényi forthrightly advocated ending oppressive feudal institutions, earning him the persecution of Hungary’s Habsburg overlords.

In March of 1838, Baron Wesselényi was in Budapest while facing trials for inciting unrest, operating a printing press without royal permission, and speaking out for Hungarian land redemption. During that bitterly cold winter, the Danube had frozen over all the way up through Vienna, but with the first thaw of springtime arriving that month, the river ice began to collapse and cause water levels to rise. At the time, Budapest’s riverbanks were inadequately constructed to resist flooding, and the riverbed between Buda and Pest was relatively shallow, causing ice floes to pile up right in the middle of downtown’s Danube stretch and block water from flowing downriver.

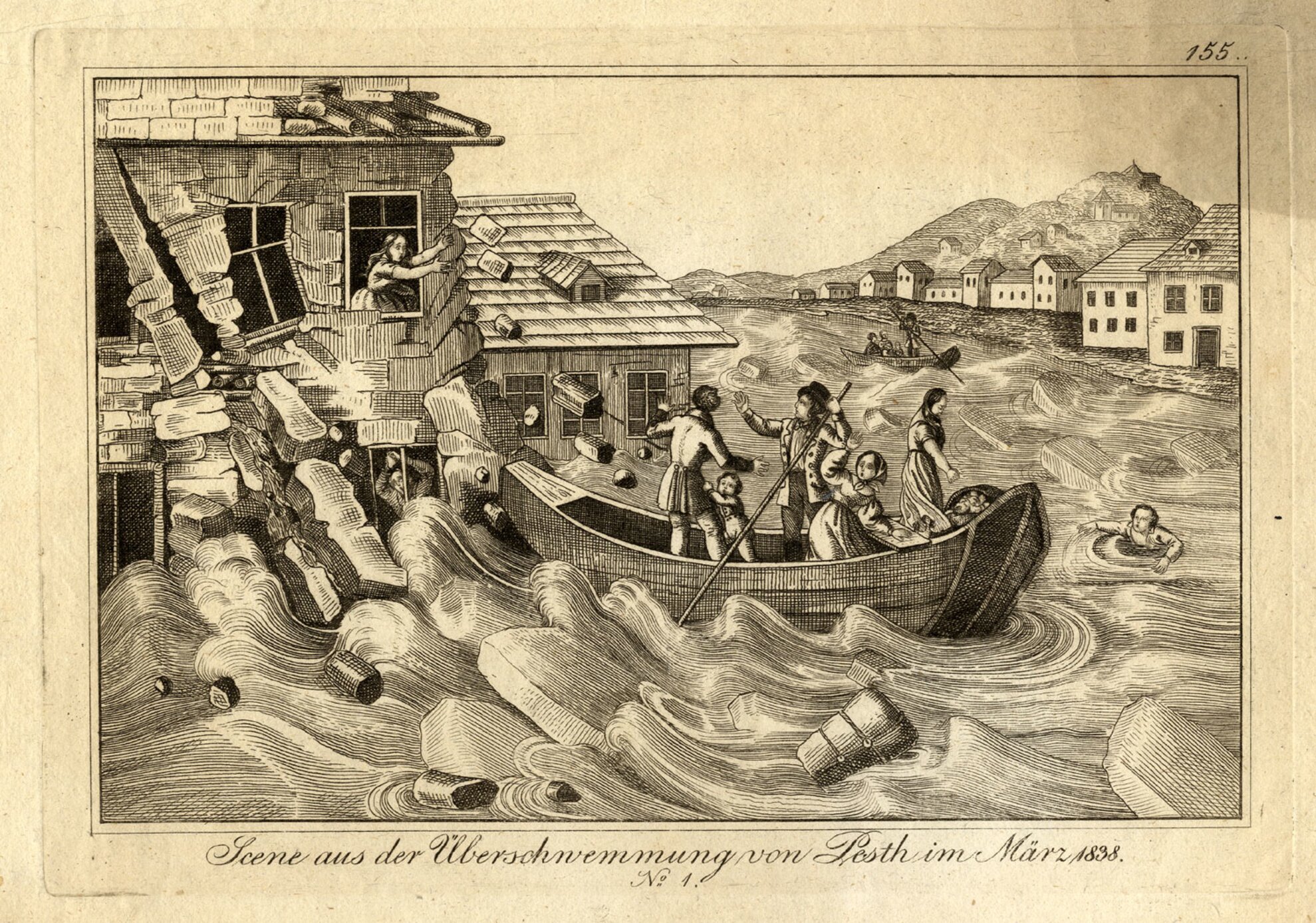

This frigid water began spilling into central Pest on March 13th after a dam broke in what is now District XIII, turning modern-day Váci Street and Deák Ferenc Street into urban rivers reminiscent of Venice. Soon another dam broke south of the city center, which temporarily allowed the river to flow and lowered flood levels… but then ice sheets again clogged the Danube around Csepel Island and the flooding spread even wider through downtown, this time with currents and small icebergs damaging the city’s haphazardly built homes.

On March 14th the springtime weather became warmer, ironically making the catastrophe worse as rising temperatures caused more river ice to melt and swell the flooding. As families clustered together on rooftops while rushing waters disintegrated the foundations below, buildings collapsed citywide and wretched survivors desperately screamed for help while floundering amid floating wreckage in the ice-cold deluge. Amid such horrific chaos all across Budapest, a rescue effort began that would continue for days, as anyone with a dinghy was called upon to shuttle stranded residents from rooftops of deteriorating houses to upper levels of taller and stronger buildings.

Ignoring his legal travails, Baron Wesselényi took a leading role among the rescuers, applying his legendary brawn to row a small boat through the swamped city center, tirelessly saving everyone he could from drowning. City administrators had never anticipated a flood of such magnitude, so the only course of action was to let the deluge run its course while Wesselényi and other heroic helpers continually searched the submerged lanes for anyone stranded in attics or clinging to chimneys. Although low-lying Óbuda sustained significant damage, the rest of Buda’s hilly terrain meant the majority of its homes were above flood levels; Pest endured most of the devastation – among the 153 deaths caused by the deluge, only two victims were in Buda.

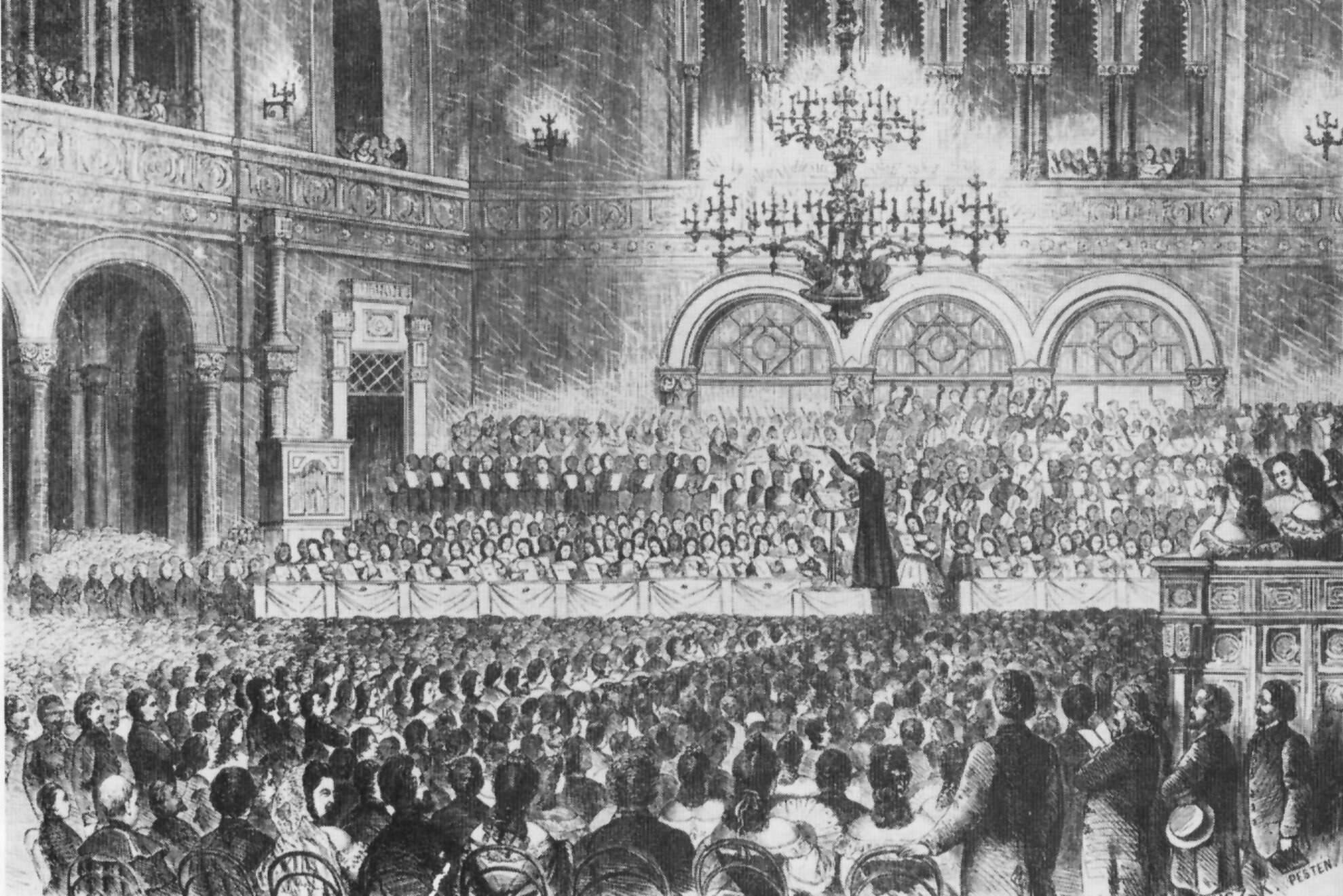

The floodwaters finally started receding by March 19th, but they left a catastrophic wake – some 50,000 city residents were suddenly homeless, and over 20,000 of them lost everything they had; in Pest, 2,281 houses collapsed completely and 827 structures were severely damaged, while Buda lost 204 houses and 262 buildings required extensive repairs. Horrified by the news, Hungarian maestro Franz Liszt – at that time a rising musical superstar – rushed to Vienna to perform benefit concerts supporting Budapest’s flood victims; the following year he continued these charity efforts here at the Pesti Vigadó hall (pictured below).

The immediate cleanup and reconstruction works were overwhelming and lasted years, but the flood’s legacy is still perceptible today in the large-scale water-management projects that were inspired by this disaster, subtly shaping the modern-day Danube waterway and numerous neighborhoods across Budapest. In the immediate years after 1838, new Budapest building codes ensured that structures must be strong enough to endure major deluges, and newly enacted municipal policies included requiring blueprints for every building proposal to be officially reviewed and approved before construction could begin.

Among 1838’s longer-term impacts, city leaders recognized that future floods could only be minimized if the Danube riverbed was deepened and its banks reinforced and equipped with sluiceways, so (after a great deal of governmental squabbling) decades-spanning water-management projects resulted in extensive drainage networks that still handle Budapest’s overflow water today. Additionally, Pest’s municipal officials encouraged city residents to resettle in northern neighborhoods further from the riverfront and central zone; the small community of Újpest (“New Pest”, comprising modern-day District IV) grew dramatically after 1838 in part because of the influx of people driven away from downtown by the flood.

But what happened to heroic Baron Wesselényi? Sadly, this altruistic aristocrat met a miserable fate – convicted by Habsburg officials for his attempts at political reform, Wesselényi was sentenced to serve three years in the dungeons below Buda Castle, where he contracted a serious eye ailment and became a wreck of a man; even after his release, Wesselényi never regained his once-legendary vitality. Although Wesselényi joined Hungary’s 1848 Revolution in a diplomatic capacity, he was soon disillusioned by the radicalization of the Magyar independence movement, similarly to Széchenyi. Left broken by his physical and political misfortunes, Wesselényi left Hungary to seek medical treatment while the revolution was still underway. The once-vigorous Baron Wesselényi died abroad in 1850, aged only 54.

Nonetheless, Wesselényi’s valiant feats during the great Budapest flood of 1838 are not forgotten, and neither are his progressive efforts to help Hungarian society – in addition to his heroic portrayal at Ferenciek Square, District VII’s ever-bustling Wesselényi Street is named in the Baron’s honor, an appropriately robust road cutting through a lively urban area that was completely submerged 180 years ago.