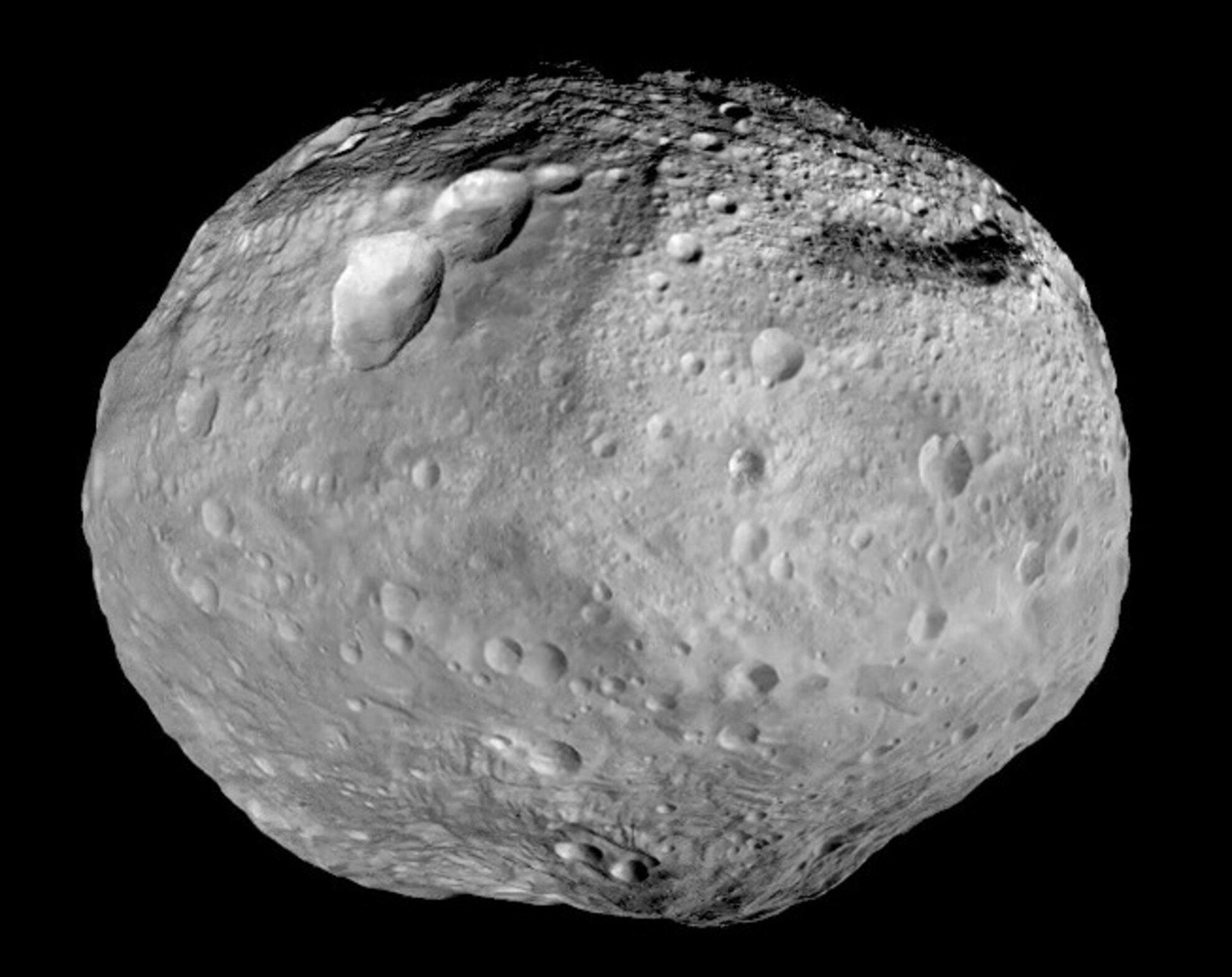

Minor planets, also known as asteroids, are dim, seemingly insignificant dots among the myriad stars lighting up the night sky, but one of them has a lot to do with the Hungarian capital, even if barely anybody knows about its existence. Once referred to only by the number 137066, this special celestial body is now named after scenic Gellért Hill.

The object was discovered on November 23, 1998 by Hungarian astronomer duo Krisztián Sárneczky and László Kiss. Following it for two months, the researchers lost track of the planet for a while, but were able to make further sightings in 2001-2002, 2005, and 2006 from Konkoly Observatory in the Mátra mountain range, and other observation points worldwide. After being observed for the required amount of time (four years), the minor planet was catalogued with a number in 2006.

Completing a full circle around the Sun in 2.7 years, the name of the planet was selected in December to mark the 200th anniversary of the one-time Uraniae Observatory on Gellért Hill. Designed by renowned Hungarian architect Mihály Pollack, the building dominated the skyline of the city for several decades (October 1815-May 1849) before being damaged during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848-49, and eventually demolished in 1867. Inspired by the momentous anniversary and the history of the prominent edifice, Hajnalka Illés, a graphic-design student at MOME University, created some stunning screen prints for a school project last year.

According to one of the discoverers, Krisztián Sárneczky, the road from taking the first shots of such an object to giving it a proper name can be a long one: “You qualify as the discoverer of a minor planet if you are the first to observe it on two different nights within the same visibility cycle. If the planet is spotted in two separate years, and no earlier discovery is found in the archives containing millions of observations, the original observer will be recorded as the rightful discoverer, but the planet must be tracked for another two years to make it all official.”

Sárneczky also told us some interesting details about the specifics of the international naming process: “After that, the Minor Planet Center – the competent body of the International Astronomical Union – assigns the planet a specific number, and for the next ten years the discoverer has the exclusive right to name the object in question. The suggestions are then either approved or rejected by a committee of elected experts hailing from a variety of nations. The rules are pretty lenient – all that’s set in stone is that politicians or soldiers can only be picked 100 years after their active period, and the use of pet names is not encouraged. Everything else goes.” We’re grateful to have a heavenly body named after Gellért Hill – maybe in the future, Hungarian astronauts can build a new Liberation Monument on top of it!