1/14

Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865)

Countless lives were spared thanks to a simple discovery by this hapless Hungarian doctor, now regarded as a brilliant pioneer of antiseptic techniques but vehemently dismissed as crazy in his own time. Born in Buda’s erstwhile Tabán district, Semmelweis became an obstetrician in Vienna, where he noticed that mothers who gave birth in a hospital where autopsies were also being performed had a much higher mortality rate than at another hospital only offering maternity services. Semmelweis realized that if doctors would wash their hands between procedures on different people (dead and alive), patients had a much greater chance of survival. Although Semmelweis’s practice indeed saved lives, he couldn’t explain why during this era before germs were accepted as a cause of disease, and most doctors were offended at the implication of their being unclean. Soon Semmelweis was driven out of Vienna’s medical community, and though he angrily appealed to obstetricians across Europe to adopt his hand-washing regimen, he was ignored and subsequently committed to an insane asylum, where he died after a beating from the guards. Now poor Semmelweis is recognized as a visionary, and is honored at his eponymous Medical History Museum in the Tabán district, while students from around the world study at Budapest’s prestigious Semmelweis University.

2/14

Theodor Herzl (1860-1904)

Few activists were as influential, controversial, and consequential as Theodor Herzl, whose life path took him from an affluent childhood in Budapest’s Jewish Quarter to becoming the father of modern political Zionism and inspiring the establishment of Israel decades after his death. The only son of a German-speaking secular-Jewish businessman, Herzl began his career as a journalist who initially supported the assimilation of Jews into European culture – but after covering the Dreyfus affair in Paris and witnessing the rampant anti-Semitism of the Belle Époque era, he decided that the only way for Judaism to survive would be the creation of a Jewish state, preferably in the religion’s historic homeland of Palestine. In 1896, Herzl published his ideas in The State of the Jews, which immediately garnered numerous supporters and detractors worldwide; to boost the movement, Herzl presented his plans to international leaders like German Emperor Wilhelm II and Turkey’s Sultan Abdulhamid II. After founding the World Zionist Organization, Herzl traveled widely to promote his proposal, but he died of heart disease aged only 44; nonetheless, his followers successfully carried on the cause. Today Herzl is mentioned in the Israeli Declaration of Independence, and the square before Budapest’s historic Dohány Street Synagogue bears his name.

3/14

Harry Houdini (1874-1926)

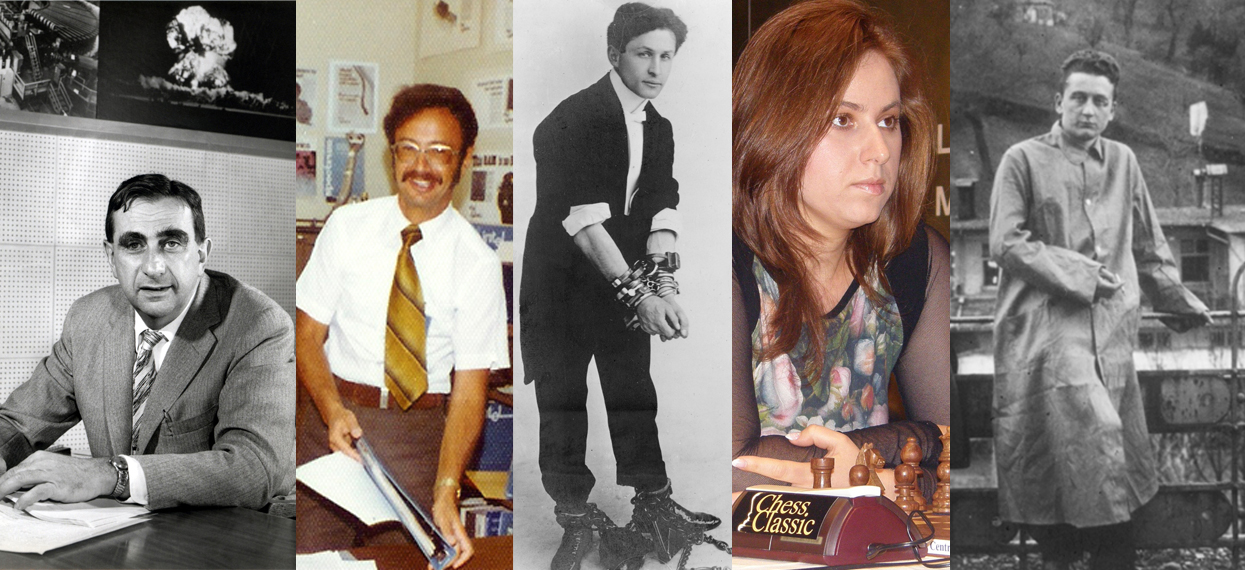

Before Harry Houdini became the world’s most famous magician – a title he arguably still holds today – he was born Erik Weisz in Pest’s Terézváros district, not far from Nyugati Station. His family moved to the USA during his childhood, and by age nine he was a trapeze artist, launching a long career as an audacious showman. After learning magic tricks as a teen, Houdini adopted his stage name and worked New York’s sideshow circuit (meeting his wife and lifelong assistant at a Coney Island performance). Houdini’s card tricks weren’t too impressive, so the athletic entertainer honed his act as an escape artist, and by 1900 he was starring in America’s top vaudeville theaters. In every nation he visited while touring Europe, Houdini challenged local police to lock him up; of course they couldn’t, earning “The Handcuff King” renown across the Continent, along with a $300 weekly salary – huge pay in those days. As Houdini’s fame grew, his tricks grew more death-defying, such as escaping from a nailed packing crate immersed underwater or digging himself out after being buried alive. By the 1920s his sensational shows earned him a fortune, paving the way for today’s magic spectaculars that are a major industry in Las Vegas and beyond. Back in Budapest, the House of Houdini appropriately honors this Magyar magician with astounding flair.

4/14

Michael Curtiz (1888-1962)

Appropriately for a man who made many of cinema history’s most legendary thrillers, the early life of Michael Curtiz is shrouded in mystery… but it’s accepted that he was born Manó Kaminer to a poor Jewish family in Budapest before embarking on an entertainment career and “Hungarianizing” his name to Mihály Kertész. After touring Europe as a traveling actor and working at the Hungarian National Theater, he got his moviemaking break by shooting Hungary’s first feature film in 1912, and by 1918 he was one of the country’s top directors. The following year, Hungary’s first communist government nationalized the movie business, so the young cineaste moved to Vienna and became one of Europe’s premier filmmakers – earning the attention of Jack and Harry Warner, who recruited him to work for them in Hollywood. Now called Michael Curtiz, the Magyar director drew on his German Expressionist influences to make American movies with groundbreaking style, and his increasingly popular films launched the careers of Bette Davis, Errol Flynn, Doris Day, and many other stars of Hollywood’s golden age. Curtiz’s prolific output of more than 100 films (in genres spanning dramas, comedies, musicals, Westerns, historical epics, and more) includes Oscar-winning classics like The Adventures of Robin Hood, Mildred Pierce, and his masterpiece, Casablanca.

5/14

Albert Szent-Györgyi (1893-1986)

Science genius, secret agent, anti-war activist – Albert Szent-Györgyi lived a fuller life than most, and everyone alive today is indebted to his discovery of vitamin C. Born to a noble Hungarian family with generations of scientists, Szent-Györgyi studied medicine at Budapest’s Semmelweis University, but his budding career was interrupted when he had to serve as an army medic in World War I. Appalled by the violence of the Great War, Szent-Györgyi shot himself in the arm and claimed it was enemy fire to get medical leave. Continuing his education, Szent-Györgyi’s brilliance landed him research positions at prestigious universities; he earned his PhD at Cambridge, then came home to work at University of Szeged. Here he experimented with an unidentified organic acid (sometimes using paprika) that turned out to be crucial vitamin C, and this discovery earned Szent-Györgyi a Nobel Prize in 1937. During WWII, Szent-Györgyi used his international renown for Hungary’s resistance movement, traveling to Cairo in 1944 under the pretense of giving a scientific lecture, when in fact he was meeting the Allies for top-secret negotiations. After moving to the USA in the late 1940s, Szent-Györgyi made great progress in muscle research and cancer analysis; he became an American citizen in 1955, and a prominent Vietnam War protestor in the ’60s.

6/14

László Bíró (1899-1985)

Among the many inventions dreamed up by Hungarians before spreading worldwide, the ballpoint pen – designed by Budapest native László Bíró – is probably the most prevalent; as humanity’s most-used writing instrument, millions of them are produced and sold every day. Raised by a Jewish family in the Magyar metropolis, Bíró began working as a journalist soon after completing school. In the pursuit of his writing career, Bíró became frustrated with the smudges and leaks inherent to the pens of the day, and though he noticed that ink used for newspaper printing dried quickly, it was too thick to flow through a fountain pen’s nib. Teaming up with his brother György (a chemist), Bíró created a new kind of pen tip featuring a tiny metal ball that turned in a socket, which would pick up fast-drying ink from an airtight cartridge before rolling it onto paper. This useful everyday device was a hit at the 1931 Budapest International Fair, and Bíró patented the invention in Paris in 1938 – but with the arrival of World War II, László and György were forced to flee Hungary for Argentina. There the brothers further developed their handheld breakthrough, and because ballpoint pens worked much better than fountain pens at high altitude, they were essential tools for Allied airmen. Today the ballpoint pen is commonly called a “biro” in many countries and Bíró’s birthday of September 29th is celebrated every year in Argentina.

7/14

John von Neumann (1903-1957)

Ingenious in numerous fields, John von Neumann is regarded as “the last representative of the great mathematicians”, though his immense contributions to physics, economics, and computer science clearly show that his mental mastery extended far beyond numbers. As the oldest sibling of a wealthy family in Hungary’s capital, von Neumann was recognized as a prodigy by age six. A star pupil at the city’s prestigious Fasori School, he studied chemistry at the University of Berlin then earned his PhD at Budapest’s ELTE (then called Pázmány Péter University). By 1929 von Neumann had published 32 major papers in mathematics, and at age 30 he earned a lifetime professorship at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, where he worked alongside Albert Einstein. While von Neumann’s foundational achievements in game theory, continuous geometry, and quantum mechanics are beyond the ability of most laymen to comprehend, his seminal work in computing paved the way to you reading this article onscreen right now. With fellow Hungarian genius Edward Teller (see below), he was a crucial contributor to the Manhattan Project, as he developed essential components of the world’s first atomic and hydrogen bombs; he also established the strategy of “mutual assured destruction” still discouraging nations from starting nuclear wars.

8/14

Edward Teller (1908-2003)

Called “the father of the hydrogen bomb” (a title he, unsurprisingly, didn’t like), Edward Teller launched humanity into the nuclear age with his earthshaking work on the Manhattan Project and the development of thermonuclear weapons. Born into a Jewish family in Budapest, young Teller witnessed Hungary’s tumultuous political transformations following World War I (leaving him scornful of both communism and fascism) and, partly due to Hungarian anti-Semitic policies of the era, he left his home country in 1926 to study in Germany. Recognized for his brilliance by his early 20s, Teller worked with Italian nuclear-physics pioneer Enrico Fermi, who inspired his career path – but when Hitler took control of Germany in 1933, Teller fled to England before becoming a professor in the United States. After making important contributions in physics and chemistry at George Washington University, Teller took a leading role in the US government’s WWII effort to build the world’s first atomic bombs, though he was already then eager to create more powerful thermonuclear weapons. Teller realized that goal in the 1950s as the mastermind behind the H-bomb, but in later years he advocated non-military nuclear projects, such as creating a new Alaskan harbor with massive nuclear explosions (also unsurprisingly, local officials did not approve).

9/14

Robert Capa (1913-1954)

The short but constantly momentous life of photographer Robert Capa resulted in many of history’s most iconic pictures, capturing scenes of many wars, historic sites, and contemporary luminaries ranging from Picasso to Bogart to Hemingway. Originally named Endre Friedmann, he joined Budapest’s leftist avant-garde art scene in his youth, and by age 18 was persecuted and driven out of Hungary; he first worked as a photographer in Berlin before being driven out again when the Nazis seized power. While living in Paris he changed his name to boost his freelance prospects, and soon began covering the Spanish Civil War; Capa’s up-close image of a freshly shot Republican militiaman, titled “The Falling Soldier”, earned him international renown. After covering China’s resistance to the Japanese invasion in 1938, Capa was embedded with US troops during their liberation of Sicily and for D-Day attacks on Omaha beach, where he shot 106 photos while under fire (all but 11 of them were destroyed in a photo-lab accident). Acclaimed for emotive portrayals of life in war that forever changed the nature of photojournalism, Capa also took portraits of movie stars (including his lover Ingrid Bergman), and he was a founder of the Magnum Photos cooperative agency; his legacy is honored in Budapest at the Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center.

10/14

Zsa Zsa Gabor (1917-2016)

Nobody would claim that Zsa Zsa Gabor changed the world with her acting skills, but as the first celebrity who was “famous for being famous”, this tabloid superstar embraced Hollywood life, brazen quips, and multiple marriages to an extreme that set the decadent standards for today’s reality-show wannabes. With multigenerational Budapest roots, the future Zsa Zsa was born Sári Gábor and began her show-business career in Vienna before being crowned Miss Hungary in 1936. During WWII, the Jewish Gábor family was forced to flee for Portugal in 1944; the budding starlet relocated to California soon afterwards, where she was immediately in demand for her European grace and seductive Hungarian accent, scoring her prominent roles in major movies like Moulin Rouge and Touch of Evil. Gabor starred in plenty of not-so-major movies as well, but by the 1960s she was primarily famous for her jet-setting lifestyle, diamond-studded wardrobe, and penchant for wealthy husbands; she was married nine times to men as diverse as American hotelier Conrad Hilton, British actor George Sanders, and Barbie-doll designer Jack Ryan. Still a household name to this day, Gabor turned fame into a way of life followed by contemporary TV personalities like Kim Kardashian, Anna Nicole Smith, and, ironically, Paris Hilton – the great-granddaughter of Zsa Zsa’s ex.

11/14

George Soros (1930-)

As one of the world’s richest and most controversial figures, tycoon and philanthropist George Soros continually influences global politics for decades now, earning praise and scorn from numerous world leaders and indisputably affecting the future with his far-reaching initiatives. As a child in a well-to-do family, the future billionaire lived at Kossuth Square; his father changed their name from Schwartz to Soros in 1936 to conceal their Jewish roots amid the country’s growing anti-Semitism, and during WWII they purchased fake documents proclaiming them as Christian to survive the Holocaust. In 1947 he emigrated to England to study at the London School of Economics, and after initially struggling to get work, Soros took an entry-level clerk position at a merchant bank, beginning a lucrative stock-trading career that led him to set up a hedge fund in 1973, which generated over $40 billion since then. Some of Soros’s moneymaking techniques are considered unscrupulous – particularly his currency-speculation investments – but he uses his wealth to support varied social causes; to boost the independence movements of Soviet-controlled countries in the 1980s, he provided funding for the education of political activists, including current Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. Soros is the founder of Budapest’s Central European University.

12/14

Andrew Grove (1936-2016)

Silicon Valley might not exist without “Andy” Grove – born András Gróf in Budapest – as this semiconductor-industry pioneer blended technical skills with innovative business management to create a new corporate model as a founder and CEO of Intel. He certainly had many challenges to overcome; as a Jewish child during WWII, he and his mother only survived because friends sheltered them, and during Hungary’s 1956 Revolution, he escaped to Austria with no money and hardly any English. Nonetheless, he managed to move to New York a year later, where he worked as a busboy while earning his bachelor’s degree; he went on to get a PhD in chemical engineering from Berkeley in 1963. Grove started out as a researcher in California’s burgeoning semiconductor business, where he learned about the integrated circuits that made the “microcomputer revolution” possible, and in 1968 he joined Intel on its first day of existence as the company’s director of engineering. Grove was instrumental in driving Intel to become the world’s largest semiconductor manufacturer and the planet’s 7th biggest company – yet he always maintained an open approach toward management, working in an ordinary cubicle that was accessible to his employees and encouraging feedback (positive or negative), thus establishing the preferred leadership style of modern IT businesses.

13/14

Ernő Rubik (1944-)

The best-selling toy of all time was basically invented by accident, as its namesake creator was simply trying to make a teaching tool, but dreamed up a perennially popular (and profitable) puzzle instead. Ernő Rubik – who was born in Budapest and has lived in Hungary throughout his entire life – started out as a sculpture student before attending the Budapest University of Technology and becoming an architecture professor at the Budapest College of Applied Arts in 1971. While “searching to find a good task for my students”, Rubik built a three-dimensional puzzle made of wooden blocks and rubber bands to demonstrate how a structure could be built with moving pieces and yet not fall apart. His students were so fascinated by this playfully challenging model that Rubik realized it might hold wider appeal, and so he applied for a patent and set out to find a manufacturer, but his entrepreneurial efforts were stymied by Hungary’s communist-controlled economy. With great persistence, Rubik managed to get his “Magic Cube” produced by a small plastics company, and in 1979 he licensed it to a US toy company, which changed the name to “Rubik’s Cube” – an immediate global sensation, with over 350 million of them made since then. Rubik utilized his success to help young engineers and industrial designers with his International Rubik Foundation.

14/14

Judit Polgár (1976-)

Breaking world records and gender barriers since childhood, Judit Polgár is the premier female chess player of all time, earning the title of Grandmaster when aged only 15 – younger than when Bobby Fischer achieved the same feat. Along with her two older sisters, Polgár grew up in a Budapest household where their father carried out a bold educational experiment: declaring that “geniuses are made, not born”, he home-schooled all three of his kids with a focus on playing chess for hours every day, and then entered them in men’s chess tournaments to prove that women were equally capable in this supremely strategic game. While both of the elder Polgár sisters excelled in their training and competitions, Judit was a true prodigy who first defeated an International Master at age 10 and a Grandmaster at age 11, and was ranked among the planet’s top 100 players by age 12. Traveling to tournaments worldwide, she faced rampant sexism during her increasingly impressive career, but Polgár continually won contest after contest to become the only woman to ever qualify for a World Championship tournament and the only woman to win a game against a reigning world number-one player, as well as beat ten former champs. After retiring from competition in 2014, Polgár is now the captain and head coach of the Hungarian national men’s chess team.