While the Jacobins are most associated with the French Revolution of 1789, their influence stretched beyond Paris. Budapest was no exception. Ruled from Vienna since the Austrians helped liberate Buda from the Turks a century earlier, Hungarians had to live with strict censorship.

Educated by Franciscans, Ignác Martinovics was a scholar, philosopher and writer who fell under the sway of the revolutionary ideas circulating in Paris. Also acting as a secret agent, he brought these concepts of equality and human rights to Budapest, and attracted a number of influential followers. One was the lawyer and writer, József Hajnóczy.

Also a translator, Hajnóczy duly rendered several enlightened and revolutionary writings sourced from Martinovics into Hungarian, corresponding frequently with his friends, most notably to the great man of Hungarian letters, Ferenc Kazinczy. As censorship became more strict, several of Hajnóczy’s unnamed works were considered dangerous. An investigation was launched to discover the identity of the author.

Returning from Sopron where he had been celebrating his engagement, the 44-year-old lawyer was arrested by the captain of police, brandishing a letter from Martinovics revealing the secrets of the conspiracy. The document had been scrutinised by the authorities in Vienna three weeks before.

Hajnóczy tossed a large packet of papers from his mailbox in front of the police chief, saying, “Here are the other letters from that inferior villain,” then followed the officers without objection.

Martinovics, Kazinczy and Hajnóczy were sentenced to death. The site of the execution was to be a patch of grass then known as the General-Wiese or General Meadow. In the 1500s, this was where the village of Logod had stood, before it was razed by the Turks.

After the Ottoman defeat of 1686, this area of open land was used for the protection of Buda Castle and for training soldiers, hence the military name. No-one was allowed to build on it, although this decree was rescinded in 1784.

Here, a decade later, at 6am on 20 May 1795, seven of the main conspirators were lined up to be beheaded. Kazinczy had been spared the death penalty but would spend more than six years in jail, then lead the resurgence of Hungarian literature in the early 1800s.

As for Martinovics, after seeing the first beheading,

he is said to have fainted and had to be dragged to his gory fate. Hajnóczy, on

the other hand, showed great dignity and composure.

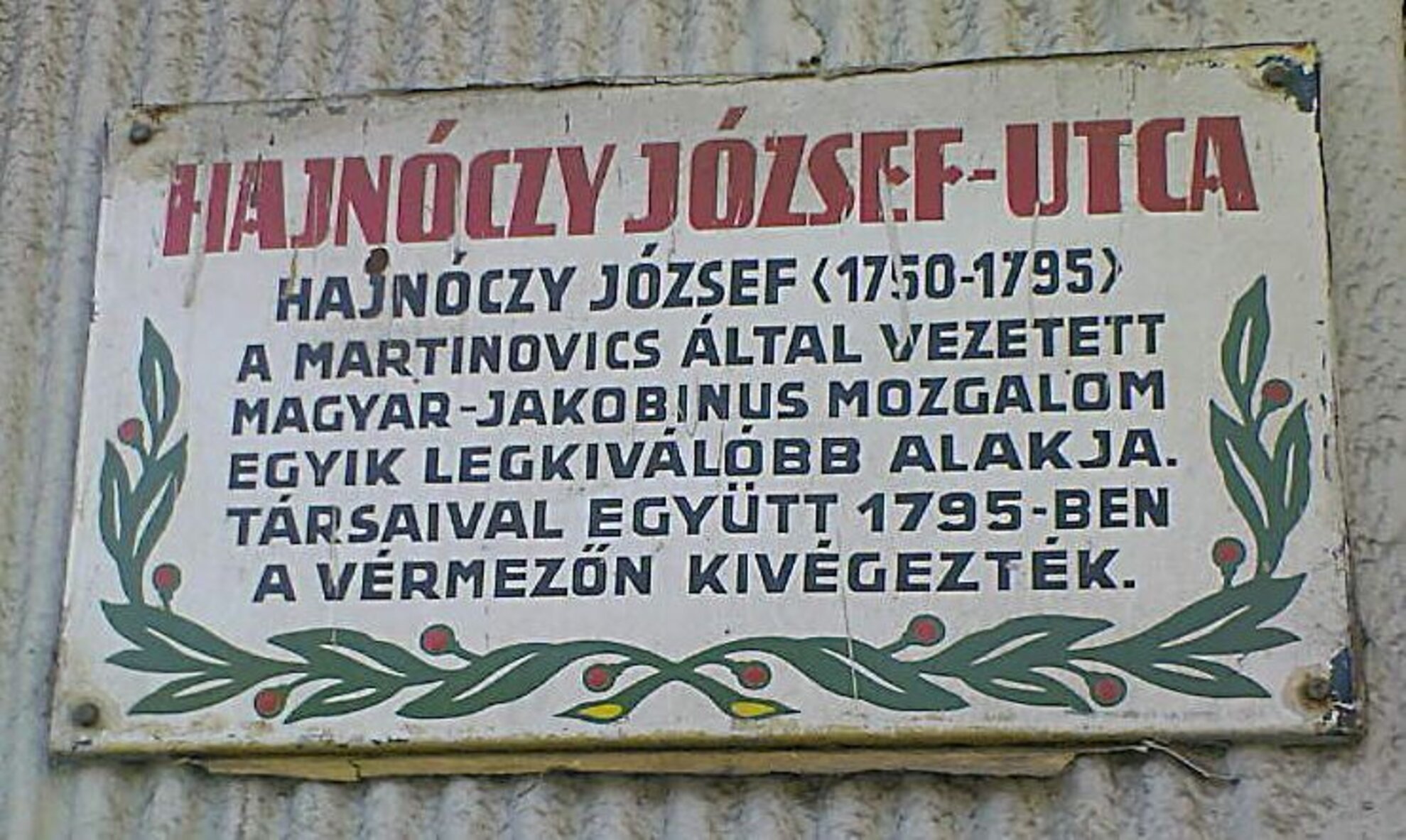

While today Martinovics is considered

a man of dubious character – although no-one really knows – his translator

and co-conspirator Hajnóczy has a street named after him, running from the site

of the execution.

And where Krisztina körút meets Varosmajor utca, a space barely resembling a square is named after the conspirators of the 1790s, Magyar jakobinusok tere. Victims of their own idealism and a repressive régime, they paid dearly for their clandestine activities. Worse would follow half a century later.