When the trend to build holiday homes spread in the late 1800s, the aristocracy and the rich bourgeoisie found the Buda hills abundant in greenery, fresh air and tranquillity. By then, however, some summer houses had already appeared, such as the Villa Hild, built in 1844, designed by the country’s busiest architect for himself and his family. Today it is the renovated home of a branch of the Hungarian Academy of Arts.

Until the

beginning of the 19th century, the Buda hills retained the character of a

charming, small mountain village, surrounded by woods, meadows and vineyards.

A

smaller inn occasionally appeared, where the weary wanderer or the gallivanting lord arriving from faraway lands could request overnight accommodation.

This peaceful rural life was finally interrupted by the cholera epidemic in Pest in 1831. Suddenly everyone realised that rural air and greenery had a much better effect on health than densely populated Pest, a fact not lost on locals today.

Due to this influx, a relatively large amount of damage was caused around the woods, so the city authorities decided to subdivide the area, allowing the richer classes fleeing the city to claim these plots. Along Zugligeti út, Svábhegy and forested Budakeszi Országút, traders, manufacturers, landowners and wealthier intellectuals arrived, enjoying this hilly idyll from late spring to early autumn.

József Hild, one of Hungary’s finest architects, and his wife, bought a plot on Budakeszi út in 1827. The site, registered as a meadow, was acquired at an auction because its former owner had accumulated so much debt that all its assets were foreclosed and its furniture and real estate sold off – and this same fate awaited the Hilds a few years later.

Hild loved Ancient Greek and Roman, as well as Italian Renaissance, art, which strongly influenced this elegant, classicist building, completed in 1844. Elements of a Venetian palace designed by his role model, 16th-century architect Andrea Palladio, defined the façade.

Surrounded by a park in the wilder, English style, the building became typical of the properties here in the 1800s. Its Corinthian columns, symmetrical and elegant, differed from the less mannered design of villas closer to town, on Gellért Hill, for example.

At home with the Hilds

“ ...Mr Hild was smiling to greet this visitor in the middle of the

tastefully arranged park of his beautiful little villa. Fragrant groups of

flowers, shaded woods and clear walkways complement one of the most pleasant

summer houses, with no less comfort than a house built with fine architectural

taste, surrounded by this well-kept pretty garden” – literary, art and fashion

magazine Honderű, 1845.

However, the building did not remain in Hild’s hands for long, as his

son was a terrible gambler and poor card player. His father had to pay off his cross-border debt and,

if that wasn’t enough, there were a few more relatives who also needed help.

In

order to be able to meet these costs, József Hild got rid of the cottage and

the plot. From then on, any new owner always tailored and shaped the building

to their liking. An extra wing was built here, a balcony walled-in there, a

stairwell moved there.

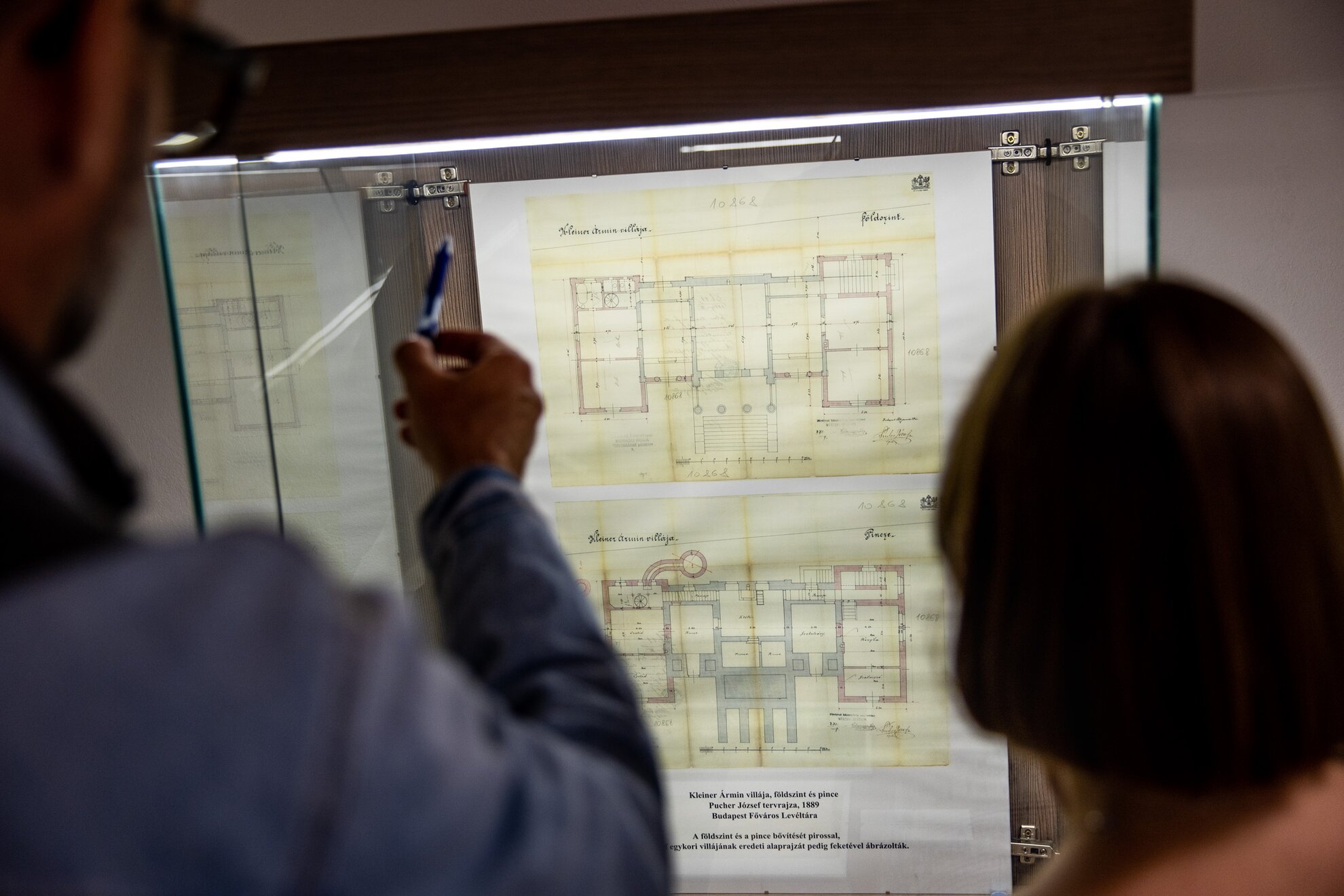

During the many major renovations that took place at the Villa Hild in

the 1880s, it became the property of Ármin Kleiner, who commissioned a rebuild from József

Pucher, an architect who knew his stuff.

For the recent renovation in 2016, the

building was renovated by comparing the plans of both Hild and Pucher. Sadly,

however, you wouldn’t have thought that big-name architects were involved, as the

workmanship was downright awful. During the revamp five years ago, it turned

out that the villa had no foundations and not only had the bricks not been laid properly, everything they could find had been packed in them.

Under post-war nationalisation, the villa was divided into several smaller, state-owned rented apartments, its condition neglected. In the 1990s, it was granted a preservation order, but stood empty in the desolation and confusion that characterised uninhabited buildings until the 2000s.

Behind the chestnut trees of Budakeszi út today, the Research Institute of Art Theory and Methodology of the Hungarian Academy of Arts spreads out across a huge garden, while the original stairs of the former villa building and the remains of the old fence and architectural fragments are dotted here and there.