Some of you may have heard that Rákóczi tér was once a notorius red-light district – but back in the 19th century, there was a whole network of bordellos around Pest. From Ó utca to Király utca to Magyar utca, the bourgeoisie and key literary figures, including Endre Ady and Gyula Krúdy, would frequent these dens, along with visiting aristocracy such as gallavanting playboy, the Prince of Wales, the later Edward VII.

As dual Habsburg capital around the time of the millennial boom, Pest had two sides to it. With the sudden onset of urban development, lust soon followed. In the 19th century, bordellos and brothels opened one after the other, with locals slipping into secret doorways for occasional pleasure, away from the hustle and bustle. At infamous nightspots, the well-to-do happily shelled out their money after dark – and not just for alcohol.

The murky world of Pest nights of yore often stirred the imagination of the writers of the day, Ady, Krúdy, Ernő Szép and Sándor Hunyady described with affection the brothels, madams and scantily clad ladies. A century of more later, this is one city walk that should best be timed for sunset.

The cathouses of District VI

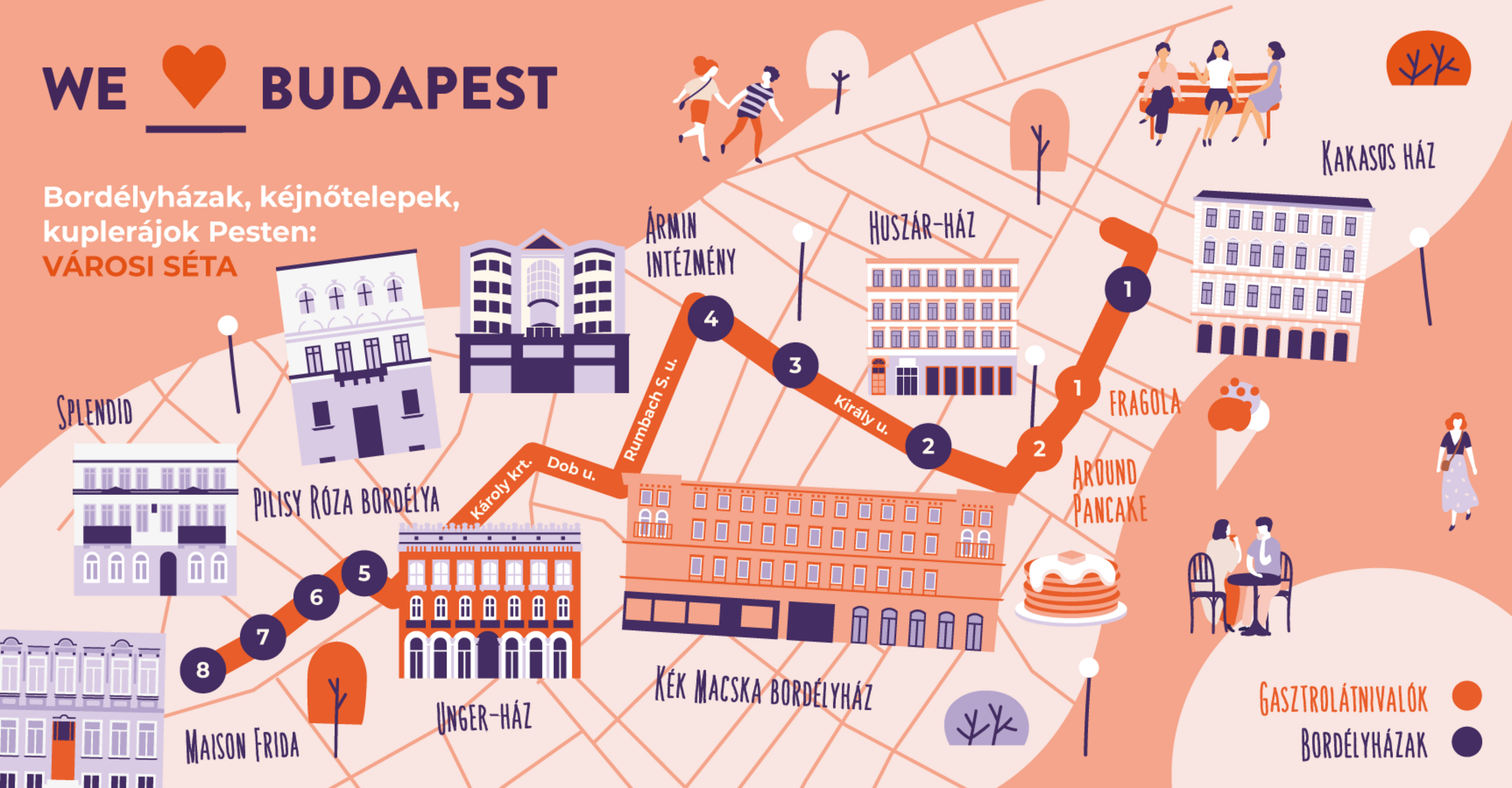

Back in the 1800s, today’s theatre district, the Sixth, was the main red-light quarter. We therefore start our walk from Nagymező utca and stroll around Pest’s sinful past. In 1867, prostitution was legalised, with varying degrees of success.

Bordellos were places of erotica and immorality, the girls working there earning quick money in the hope of a better life. Nagymező utca, Mozsár utca and Ó utca were overcrowded with such lucrative places. At the turn of the century, spending increased, more and more had to be paid for maintenance, furniture, food and drink, and this led to more expensive services, so these cheaper places became especially popular.

The first stop of our walk is the certain Kakasos (’Rooster’) House at Ó utca 33, where Krúdy also enjoyed a few nights, and not just in any bed, but the madam’s herself. Ó utca was never a model of nobility and good manners, but Jolán Marinovics almost demanded gallant behaviour from her guests.

In her house were poets, dictionary compilers and reporters and, of course, Krúdy, who used his visits to the maximum, regularly going into the kitchen to eat and cancelling out his debts by writing about the goings-on here. He regularly mentioned the madam in his stories as Johanna, Steinné or Jánoska. Even a portrait of esteemed writer Mór Jókai hung on the wall here, as he also liked to visit the place. According to him, it was strictly because of the kitchen, although when he was caught red-handed, he always said he had wanted to adopt Jolán's daughters.

Móni bácsi, Blue Cat & Ármin’s

Returning to Nagymező utca, where men could find love in every second house, you may wish to indulge in pleasure of a different kind and break off from the walk to enjoy an ice cream at Fragola or tasty dessert at Around Pancake.

Going back to the task at hand, Huszár House on the corner of Király utca and Kis Diófa utca once belonged to a certain Móni bácsi, his title (’Uncle’) indicating a certain reverence. The house was first a pub, then a dubious nightclub called Grand Café Hunyadi Mulató, frequented by artists,

Later, Árpád Mandl, whom everyone called Móni bácsi, opened a ’musical café’ where women were not necessarily appreciated for their voice or acting talent. The Austrian comedian did not receive much revenue from the nightclub, but from the brothel at the back of the building, where guests could take the waitresses. The place got a new owner and changed its name after World War I, and its function remained in place until the 1950s.

One of the most fashionable spots was the Kék Macska, the ’Blue Cat’ at Király utca 15, famous throughout Europe. Today the entrance to the Gozsdu Udvar, this was the scene of frantic activity, even by Jókai’s standards, but the Hungarian aristocracy considered it chic, given the female performers and dancers.

Not only the later Edward VII but also Crown Prince Rudolf and Herbert von Bismarck, son of the German imperial chancellor, were visitors. On one particularly lively night, the latter was seen dancing around the Blue Cat in his birthday suit, although it was the audience whom the police then dealt with.

You could almost stop at every doorway on Király utca, because almost every one has its own lurid past, but the point of interest should be number 16. Activities took place in this Neo-Renaissance building, which the rest of society considered to be filthy and dangerous. Ármin’s was a place of leisure, musical farce, chansons and dancing, where the country’s leading actor/singer of the day, Károly Baumann, also appeared, let’s say, and where the entertainment ran beyond the show on stage. In 1896, it was forced to close due to an invasion of lice.

The luxury brothels of Magyar utca

As we approach the city centre, the standard of bordellos also rises. The urban passageway of Unger House wasn’t exactly a brothel, but prostitutes lived there, and the dark doorways saw many a clench. From this passage, you reach Károlyi-kert, the pretty pocket park near Astoria. Surrounding it was a many a brothel, hidden behind velvet curtains.

With its windows covered with pink curtains and balcony overlooking Károlyi-kert the “friendliest house in Pest” awaited guests at Magyar utca 20. Here the madam, Róza Pilisy (Schumayer), not only offered pleasure but often music and poetry dinners. As well as men, actresses sometimes turned up among the guests, although they made their leave after dinner. Krúdy was also a regular here and, just as he won over the madam on Ó utca, Róza Pilisy became his as well.

At Róza’s brothel, guests were greeted in the salon, where soft music played, food and drink were offered, and lively social banter ensued. The men could see the girls quite openly as they moved around freely. The madam had bought the house on a joint-stock basis, its furnishings created by carpenter Endre Thék, who also carved the wall decorations of St Stephen's Hall at Buda Castle and the Prime Minister's desk in Parliament. Here, basic admission was 200 crowns, the equivalent of a teacher’s salary, but, in addition to carnal pleasure, it also included socialising, good food and music.

Walking further round Magyar utca,

towards today’s Mélypont Presszó,

you find the Maison Frida at number 29 and House No.34. The former was bought by

Ede Östreicher and his wife with the immediate aim of opening a brothel. In

1905, it started operating with 14 girls, during which time they repeatedly

broke into law. He allegedly found a military officer in one of the rooms set

aside for his wife, who, of course, was not alone.

In jealousy and rage, he

ended things with his wife first and then with himself, taking his own life.

There is an apartment house on the site of Maison Frida today, but the fire-red

door strongly suggests its former function. The last point of our walk is House

No.34, which changed hands several times, but Lipó Schlesinger and his wife again

bought it specifically for the purpose of running a bordello, not the only one

they had in town.

In 1926, the laws were tightened, no new brothel permits were

issued, and the old ones were revoked, so Magyar utca 34 was turned into a

garrison hotel called Splendid, which was a place for secret trysts and hot

nights until the 1940s.