The forebears of István Széchenyi were one of the most influential dynasties in the economic, political and intellectual affairs of Hungary. They were granted noble status for their services as soldiers on border fortresses and later made their fortune in agriculture.

Never ones to squander, the philanthropic Széchenys, only put capital into worthy causes – more precisely, to the growth and modernisation of their beloved Budapest. Ferenc Széchényi, István’s father, spent his life working for the public good and his son was ready to follow in his footsteps and dedicate himself to the creation of a flourishing metropolis.

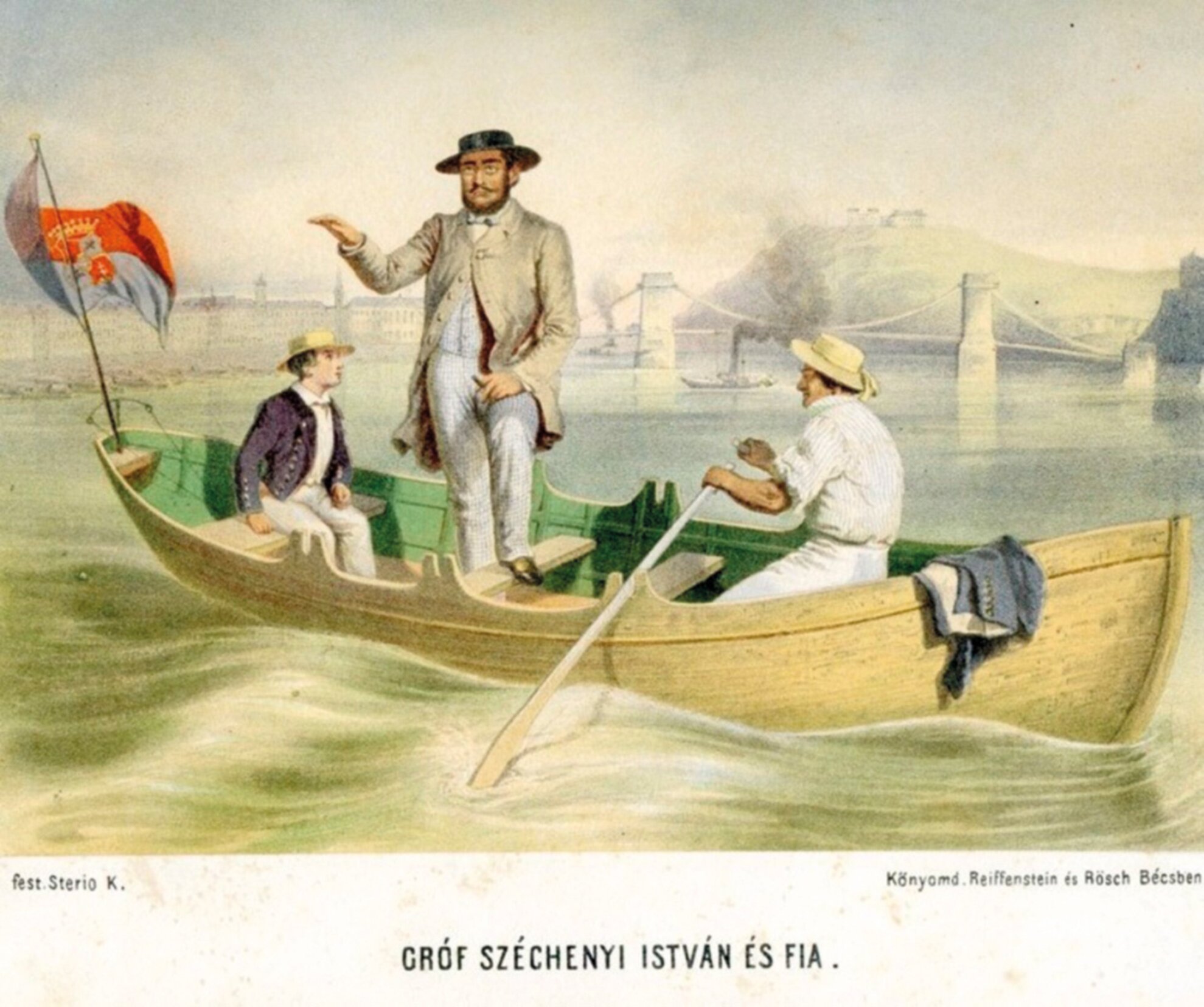

Before entering politics, the young István Széchenyi joined the army and spent 17 years in the military, taking part in the Napoleonic Wars. Legend has it that after the Battle of Raab, Széchenyi risked his life by outmanoeuvring French troops and rowing across the Danube to help link the two Austrian armies.

Despite being granted several military decorations, Széchenyi was never promoted to major, a disappointment that caused him to pursue a civilian career.

His upbringing gave him a zest for learning

and self-education which he fully embraced during study trips to France,

England, Italy and Turkey. Széchenyi realised how far Hungary lagged behind in

terms of economic, institutional and social development.

He was fascinated by

the technological novelties he saw and took detailed notes and drew rough

sketches in his journal to bring them home to Hungary.

He aimed to bridge the gap by establishing public institutions,

introducing reforms, embellishing the cityscape of Pest and introducing

Hungarians to the illustrious world of horse racing. His plan was to lure share

companies and the wealthy élite into Budapest and boost the city’s economic and

intellectual development.

In England, he learned the ways of horse breeding and

racing in the company of fellow Hungarian statesman, Miklós Wesselényi.

Wesselényi was the one who encouraged Széchenyi to improve his Hungarian skills which he had neglected all through his life in favour of German. There was a huge sensation when Széchenyi rose to speak in Hungarian during the 1825 Diet to take a stand on the cultivation of the Hungarian language and the establishment of an Academy of Sciences. Speeches were usually delivered in Latin.

Széchenyi was so ambitious and passionate about his plans that he offered one year’s income from his estate to establish the academy, asking public figures, factory owners and aristocrats to join the funding of his initiative. Surrounded by ambitious statesmen and politicians, he was also motivated by something more unfathomable: love.

The younger Széchenyi was a well-known womaniser who turned the heads of single ladies and married women alike. He was no stranger to the world of brothels. Mothers cautioned their daughters against him, and he was turned down several times because of his bad reputation.

Széchenyi first laid eyes on Seilern

Crescence, his future wife, when she was still married to her first husband,

Károly Zichy, who died in 1834. After 11 years of discreet extramarital

courtship, Crescence and Széchenyi could finally be together after the widow

finally passed a year of mourning.

Crescence was the one who lit up the flames

of patriotism within Széchenyi, who once said: “I only knew 24 Hungarian

words – and even those, incorrectly – but still stood up as a magnate in

opposition and made an offer of 60,000 forints. For what, I still do not

exactly know to this day, but eventually it became the Hungarian Academy of

Sciences”.

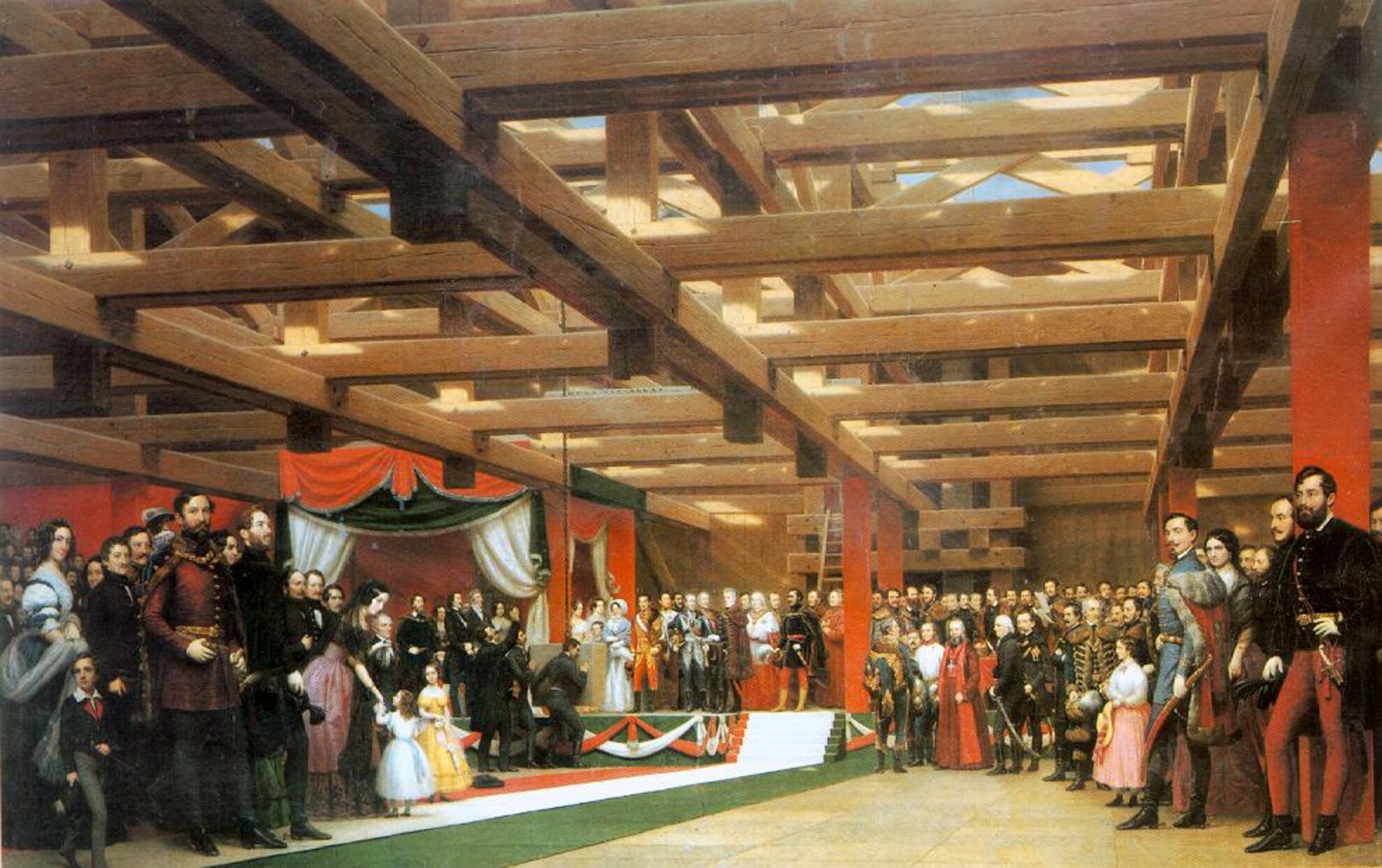

About the same time, he established the academy,

Széchenyi organised the National Casino forum in 1828 to provide scope for both

light-hearted conversation and political discussion all in the name of cultural

development.

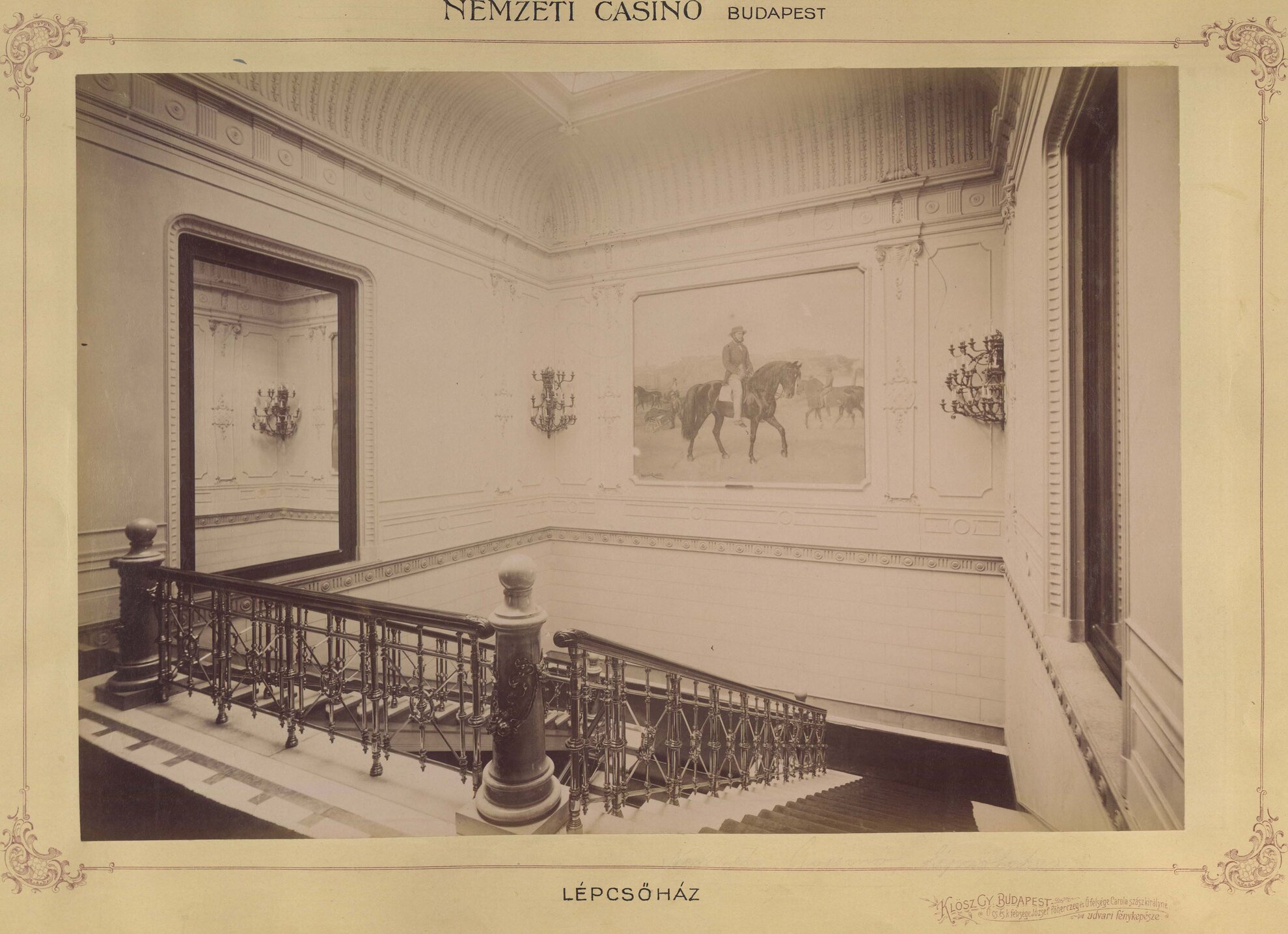

Its meetings were held at Vogel House on Dorottya utca, along with

the now demolished Lloyd Palace. Up until the end of World War II, Miklós Ybl’s

Cziráky Palace housed the Casino.

The National Casino

As Széchenyi once said: “Hungary needed a

distinctive and splendid gathering point where the intelligent and well-educated

men of the élite could enjoy cordial conversation or exchange economic,

scientific and artistic views after reading the day’s political newspapers”.

His greatest achievement was the construction

of a permanent crossing between Pest and Buda, the magnificent Széchenyi Chain

Bridge, which he never crossed over in his entire life. After years of uncertainty,

its renovation will finally take place in 2021.

Before its original construction,

a pontoon bridge linked the banks of the Danube, usually out of commission in

winter due to the drifting ice on the river. Traffic would stop for months.

Széchenyi’s journal entries reveal that he had to pay 25 forints to board a

barge to get across the icy Danube to attend his father’s funeral. A permanent

bridge became his overriding obsession.

So devoted was Széchenyi was to his project

that he was involved in everything, from pre-planning to the resolution of

final economic and technological difficulties.

When the bridge’s chain

suspension was installed, one of the pieces fell due to a mechanical failure,

whipping off the scaffolding upon which Széchenyi and his workers were standing

on. Luckily, the statesman managed to swim to the bank safely.

Besides establishing renowned institutions, Széchenyi had an active political role. He was the appointed Minister of Transport during the Batthyány Government of 1848 and became involved in serious debate with fellow statesman Lajos Kossuth, governor-president of Hungary during the revolution of 1848–49.

Throughout his life, Széchenyi had the

welfare of the Hungarian nation at heart and strived to achieve a better future

for all. He may also be defined as too much of an idealist, someone who

couldn’t deal with the fact that his ideas could not be implemented as smoothly

as he planned them to be.

In the end, this perfectionism became his undoing. In

September 1848, he was taken to the private asylum of Dr Gustav Görgen in

Döbling, where he stayed until he took his own life in 1860. The bridge he never saw completed had

been unveiled in 1849.