In Budapest’s hub of luxury hotels, along the Danube Promenade, the Marriott stands out. Look closer, however, and you see a large memorial plaque, not commemorating its predecessor, the Hungária Nagyszálló, but the fact that composer Richard Wagner came here in 1875.

The Hungária Nagyszálló, which adorned the Danube Promenade for eight decades, was built according to the plans of Antal Szkalnitzky and Henrik Koch. The idea to open a hotel on the riverbank is linked, inevitably, to Széchenyi, but not Count István whose Chain Bridge had been unveiled nearby in 1849. It was his son Ödön who founded First Hungarian Hotels in 1868, for the express purpose of building them. Work began that very year even though Szkalnitzky’s design was one of many to come before the decision-makers.

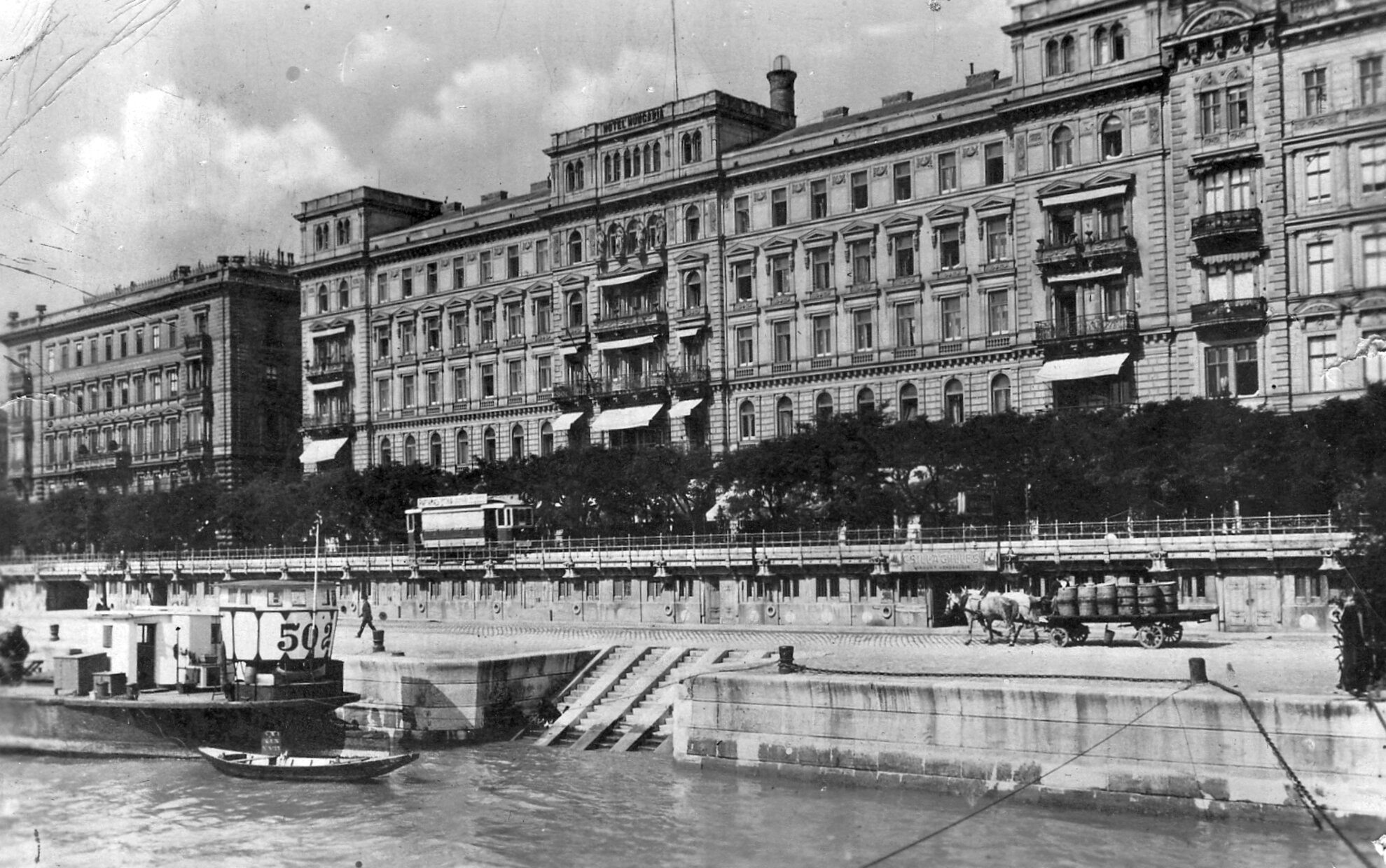

Opened in 1871, the 302-room Hungária Nagyszálló was one of the most modern and beautiful hotels of the day. Its many facilities included a telegraph service and, later, a lift.

In 1872, the Pest Wagner Association was founded here, headed by the famed Count Albert Apponyi. Invited by the board, in March 1875 Wagner arrived at the Hungária Nagyszálló in the company of his wife, Cosima, daughter of Franz Liszt.

The plaque, unveiled in 1933, later went the way of the Habsburg-era hotel but a new one was mounted by the Richard Wagner Society in 2013. Cosima was not the only Liszt to stay here, as her father was another guest, and only one of many famous figures who slept here around the turn of the century.

Edward VII when the playboy Prince of Wales, US president Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Edison, and composers Giacomo Puccini, Richard Strauss and Franz Lehár, all passed through, not to mention the wife of hotel-chain owner César Ritz, Marie-Louise, who came to Budapest to check out the local competition and opportunities.

The biggest ballyhoo surrounded the arrival in 1900 of the Persian shah, who came with an enormous entourage, booking 84 of Hungária’s 302 rooms.

Shortly before, in 1893, Tivadar Puskás, inventor of the telephone exchange, had died of a heart attack here, when only 48. By chance, the first telephone was officially put on display here in 1877.

Another presentation was Mihály Munkácsy’s Golgotha, in 1884. One third of the artist’s Biblical trilogy today on view at the Déri Museum in Debrecen, it would cross the Atlantic several times before being bought by the Hungarian State for $5.7 million in 2014.

The Hungária Nagyszálló was therefore not only a luxury hotel, but a centre of social and cultural life, with a restaurant, café, a bank and a main office of State railway MÁV. Balls, carnivals, parties and concerts were regular occurrences.

Change first came in 1919, during the short-lived Soviet Republic. The building was expropriated by the Communists and renamed the Soviet House. It became the seat of the Revolutionary Governing Council, where the commissars lived, including the bloodthirsty Tibor Szamuely, head of the paramilitary Lenin Boys. After the fall of the Soviet Republic a few months later, the hotel regained its original function.

It lasted until World War II. In the last days of fighting in early 1945, during the Siege of Budapest, the hotel was bombed to such an extent that the fire raged for three days. As Hungária was left in complete ruins, it was completely demolished and the Duna InterContinental was built in its place between 1966 and 1969.

A century after Wagner and Liszt, it would welcome VIPs of a different kind, such as Elizabeth Taylor and her Hollywood fraternity, before it became the Marriott in 1993.