If you’ve ever been curious about the views, buildings and atmosphere of fin-de-siècle Budapest, sooner or later you’ll be poring over the photographs of György Klösz. This German photographer created images of the city to order from the 1870s onwards.

How the Tabán, former City Hall or various palaces looked before they were demolished, we know from his photos, as well as the size of the crowd that gathered for the funeral procession of statesman Lajos Kossuth.

He began his career in Vienna, arriving in Pest in 1866, where he and his two colleagues opened their light room on the corner of today's Petőfi Sándor utca and Régi posta utca. Back then, Klösz had a passion for portrait photography. Statesmen, poets, scientists and actors turned up at his studio, but as there was quite a lot of competition in the city for portraiture, Klösz began looking in different directions.

This is how he became familiar with the Budapest of the 1870s. Buildings, squares and streets all came into focus. He captured the important events of the 19th century: Kossuth’s funeral procession, the construction of Nyugati station and the first underground line, and all the projects surrounding the millennial celebrations of 1896.

The construction of Elizabeth Bridge and Liberty Bridge redrew the cityscape

so dramatically that the local authorities suggested that it would be a good

idea to capture their image before demolition to preserve for posterity how the

capital once looked.

Klösz was already a recognised and well-established

photographer by then, so who better to do the job? His first major assignment

was to photograph the Tabán neighbourhood before its transformation, and he

often took his pictures just at the very last moment.

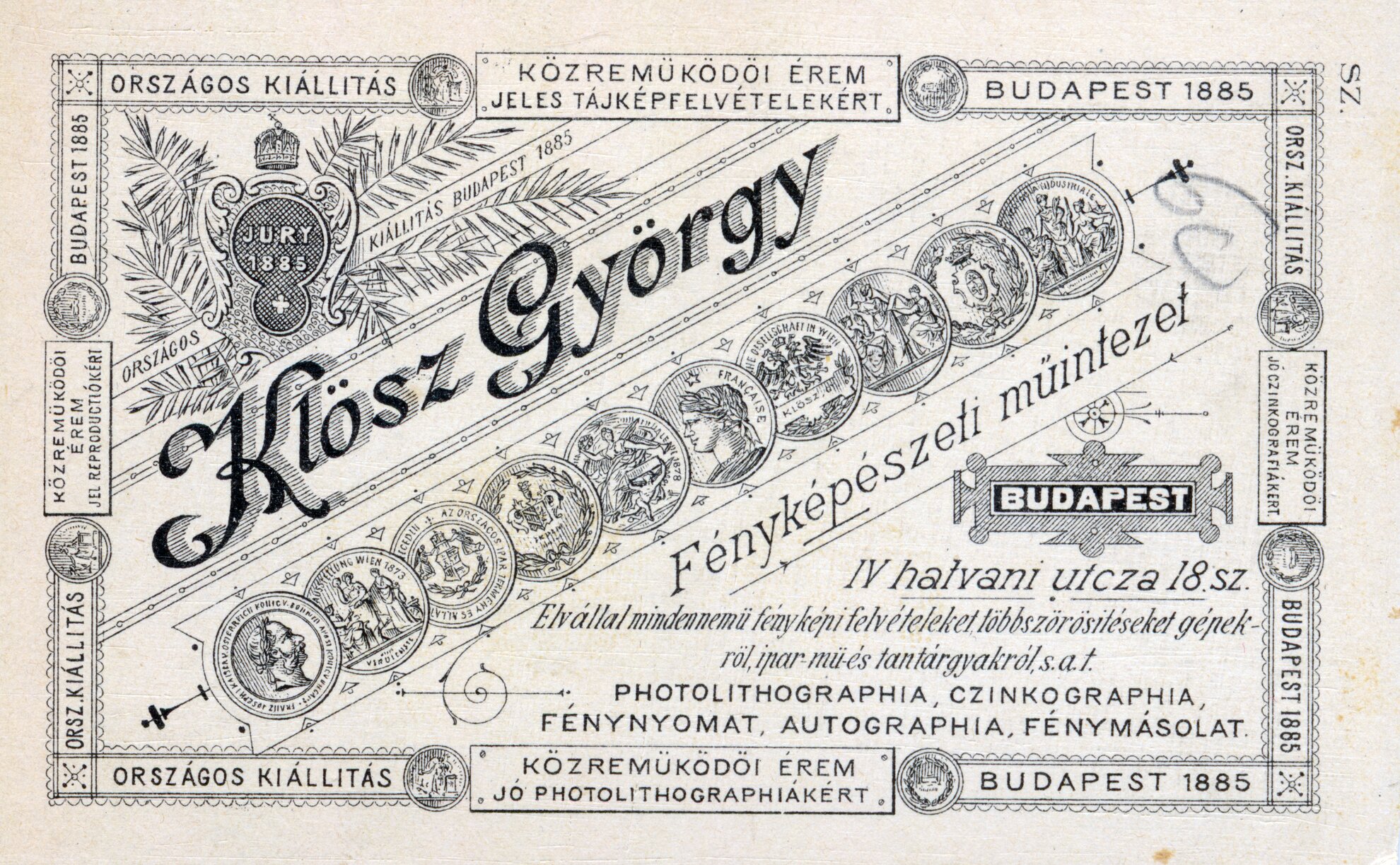

While documenting Budapest’s transformation into a major metropolis, he also proved to be a skilled businessman: he regularly advertised his services on posters and in newspapers, using a printing press. From the light room on Régi posta utca, he built a studio at Ferenciek Bazár, and later his own villa and studio on Városligeti fasor, as well as an 800-square-metre building which he used as a printing house.

After a while, in fact, he was not only involved in taking photographs, but also in reproducing them, and even later in making maps. He also created the site plan for the 25th anniversary of the coronation. At the Millennial Exhibition, he presented his panoramic series depicting the entire length of Andrássy út on a 1:100 scale.

Although originally trained as a pharmacist, by the turn of the century

he had become the number one photographer in the city. Step by step, he

established the country’s most important photographic and printing company,

founded the Union of Hungarian Photographers and became the vice-president of

the National Association of Photographers.

He was interested in every new development, not only trying them out, but also introducing them to the domestic audience. His studio

had the first passenger lift in Hungary, and Klösz was also one of the first

domestic importers of dry plates used to take pictures.

With his camera, he captured every detail of Budapest as it became a

world city, the floods and the smoky suburbs, where he photographed the

everyday life of factories, mills and slaughterhouses, as well as the communities outside town.

If György Klösz hadn’t given up portrait photography, then his

images of celebrities in their pomp in the late 1890s would not have existed – but

now they can be admired for all time.