There was a time when the dividing line between the river and Budapest did not exist, or at least not so markedly. From the Middle Ages until the early 1800s, when the construction of built embankments began in Pest, the city was characterised by natural waterfronts, along which were no major structures.

The situation changed in 1808: the authorities approved an urban development plan of Pest, according to which: “The bank of the Danube from the boat bridge to Lake Molnár in Ferencváros must be covered with stone blocks, the bad road [between the today’s Vigadó and Szabadság Bridge] must be equipped with a stone barrier and a footpath. On the banks of the Danube, a straight line of houses must be built”.

The flood of 1838 finally brought an even greater change: a dialogue began on the construction of dams and the rehabilitation of the waterfront. The idea for a protective dam comes from Count István Széchenyi, while the final quay construction began in 1853, when the Danube Steamship Company built a 345-metre stone shore at the Pest end of the Chain Bridge.

This was later rebuilt, on the bank facing Fővám tér. In the 1860s, the filling in of the shores also rose to prominence: the valuable plots of land created could thus be built upon by the City. But, as in all ages, there were opponents to this development. Writer/propagandist Mihály Táncsics called for the provision of parks and airy spaces instead of land speculation – just like the people of the capital today.

In the 1890s and 1900s, there was still an active commercial life along the loading bays: Petőfi tér was bustling with vendors from the settlements along the Danube at dawn, and the place was full of the smell of fresh fish, fruit and vegetables.

Beyond the market, the promenades were popular places for leisure and recreation. People walked in the spring sunshine, children jumped into the Danube – although this was already forbidden – while anglers fished and kayakers paddled. Romantic youngsters mingled with writers, poets and musicians, enlivening the cultural atmosphere of the quay with their presence.

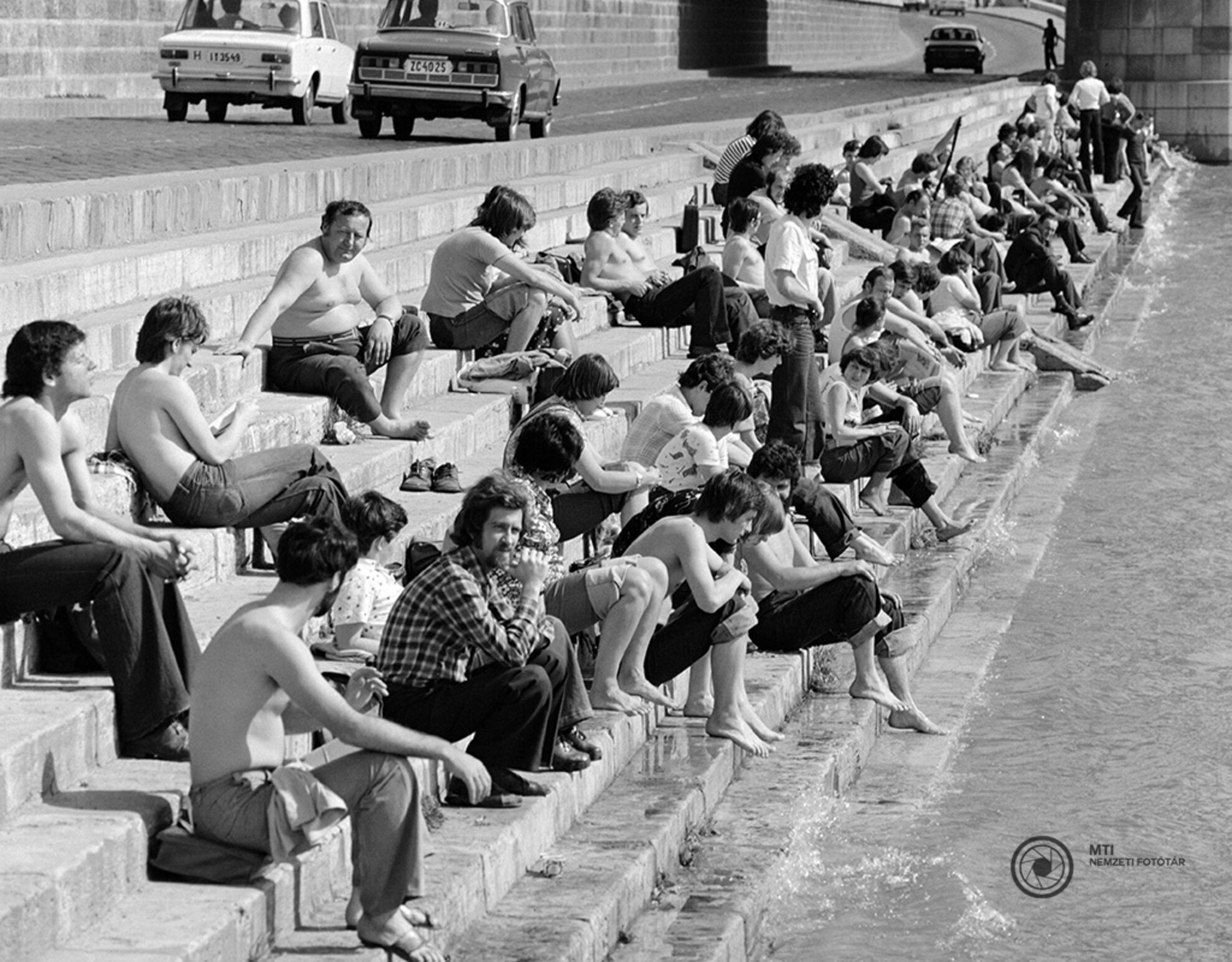

Even as late as the ’60s and ’70s, one of the city’s most popular sunbathing spots and meeting places was the stairs of the Pest embankment. For students, this was the so-called Danube department, pleasant to study and have fun.

However, with the spread of cars and increase in traffic passing through the city centre, the crowds thinned and, by the 2000s, disappeared, to be replaced by engine noise, busy concrete and constant fumes. Why linger on the steps?

Sometime in 2010, the quays started to flourish again: the section between Árpád Bridge and Kossuth tér became walkable. The RAK-PARK tender sought to reactivate the empty downtown Danube bank, motivating young architecture and urban design students to re-establish direct contact between the city and water. Civil initiatives, most notably from urban activists Valyo, strengthened the bond between city and Danube.

The summer closure of the Pest embankment from cars now offers an alternative view and a sense of further possibilities. Browsing these archive photos, however, you can see that the proximity of water has always been attractive – surely it would be worth opening the quay for more weekends, even weeks?