Located in Máriaremete, the Devil’s Trench (Ördög-árok) runs for about 20 kilometres on the Buda side of the city. In some places it hides beneath pavement, other times the unassuming nature of the stream would never have you believe that it was once the sewer system for Buda, when its reputation was ominous and malodorous.

The stream originates on the border of Nagykovácsi, passes through Remeteszőlős, and emerges lush and picturesque in Remete gorge. During our hike through the gorge in 2019, we caught it in its waterlogged state, as it is not unusual to find the creek-bed dry. When flowing, the stream travels a total of 1.5 kilometres between steep cliffs and hillsides.

From here, through Máriaremete, the ditch leads

to Hűvösvölgy, passing Nagyrét, where it merges with the Little Devil's

Ditch, Kis-Ördög-árok. It winds

roughly parallel to Máriaremetei út and Hűvösvölgyi út, and then disappears

underground at the stop of tram lines 56 and 61.

The water then passes

under your feet unseen, through Városmajor, Vérmező and Horváth Garden, all the

way to its final destination: Döbrentei tér, where it flows into the Danube

at the Buda end of Elizabeth Bridge.

From the 14th century, the ditch was also called Paulus Creek (after St Paul the Hermit), later Kovácsi Creek, and then Teufelsgraben. From this name, the Hungarian rendition of Devil’s Ditch finally caught on. In the absence of sewerage, the ditch was the sewer of Buda, crossing the city like a stinking gulley of filth, causing distinct displeasure for local residents. According to Vasárnapi Újság:

Not so lovely Buda

“The stinking mud and sewage of centuries have gathered in the Devil's Trench, stuffing its miasma in the otherwise clean and fresh air of Buda, and carrying the threatening danger of plague by evaporating it into the surrounding houses. In this large, almost vaulted ditch, all the debris of hundreds and hundreds of canals was often stuck for weeks, until some merciful downpour took on the role of sewer cleaner, rushing through the cold, flat of the ditch, and transporting some of its stinking contents into the riverbed near the Danube.”

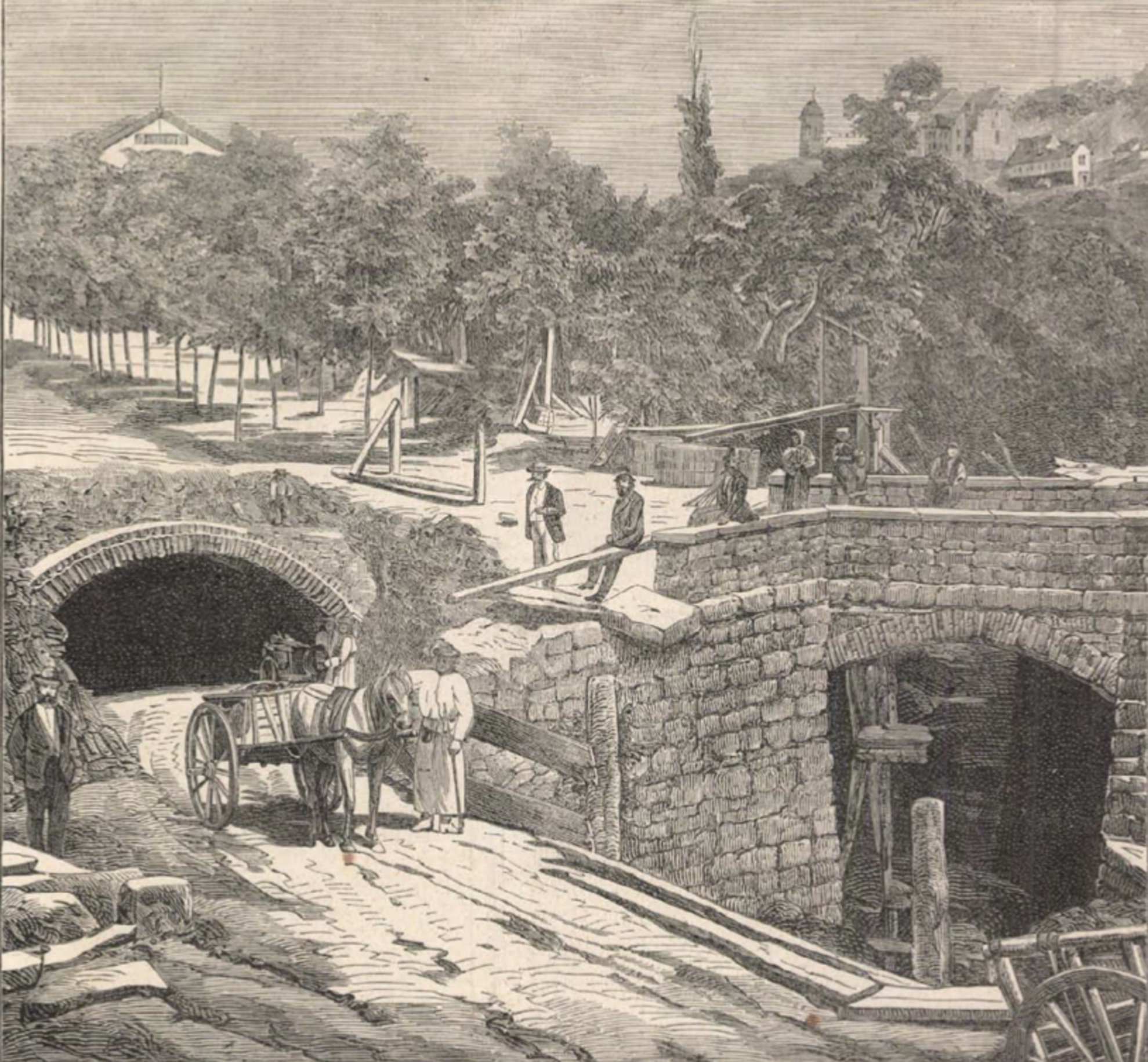

While healthy rainfalls were a cleanser to the system, massive storms carried a constant threat of destroying large sections of the ditch. Only remnants remained after the flood of 1837, for example. Therefore in 1872, to the delight of the citizens of Buda, the City's Public Works ordered it to be vaulted, which began at Horváth Garden.

The relief was only short-lived, however, as just after its partial coverage, a tremendous rain and hail descended upon the city on a warm Saturday in June 1875, and the vault of the Devil’s Trench could not bear the weight of the water and the eroded soil, which itself spared neither the two-storey houses built above it, nor the lives of its inhabitants.

Biblical destruction

“We have no words to describe the torrential rain which,

in half an hour, completely overwhelmed the lake on the site of the Biblical meadow and Városmajor, filling the lowland plateau of Vérmező with swirling, raging,

wildly flowing waves, kneading the Devil’s Ditch and tilting walls, fences,

bridges and dams, smashing Krisztinaváros and the Tabán, and shredding the closed gates

with the force of city-destroying cannons, and tearing up the old vault of the

Devil’s Trench as if it had been blown into the air by dynamite. Houses were

turned to rubble as if they were houses of cards," wrote Vasárnapi Újság.

The writers concluded by saying the natural disaster was of such magnitude that it would be remembered in posterity along with the Great Flood of 1838.

The water poured like a waterfall through the windows of the houses of Attila út, with cellars full of foul, stinking mud and covering furniture with nearly a foot’s worth. Many residents on the streets were also blocked from escaping the terror due to the raging waters, and several died in the tragedy. Apart from lofty Karátsonyi Palace on Iskola utca, there was no house spared the tumult.

Force of nature

“When the ditch bed was filled with pouring water, always

whipped higher by the flood of other streams, the squeezed waterfall sought its

way forward, swelling higher and higher, and toppling the sides of the houses

in a matter of moments. It was as easy a job for the torrent as it would be for

us to scoop the riverbank with a ladle. The ruptured water than flooded the

rooms to the roof in a minute, knocking down the side walls, smashing

everything within it, and by the end this was concluded, it carried the results

of its destruction in mad waves into the Danube, above which a dark night sat.

God be merciful to the poor souls who were in their homes at the moment of the

ruin and the flood of fury!”

During the restoration works, donations were collected and the vault was rebuilt with extra care, including paving the bedrock. By the end of 1920, the canal continued to be covered until it reached Városmajor. But the connection between Devil’s Trench and sewage is not over: as a main collection channel, it carried the Buda wastewater to the Danube until the connection of the Csepel Central Wastewater Treatment Plant in the early 2010s. Local news portal Index released a video (in Hungarian) of the Trench and its water system in 2013, even exploring the underground portions – and immediately advising that viewers should not attempt to do this on their own, as it is extremely dangerous.

Sources:

- Vasárnapi Újság, 1875. Fővárosi tárczák Borostyáni Nándortól: A borzalmak éjjele, page 425.

- Vasárnapi Újság, 1874. Egy részlet a budai ördögárokból, page 211.

- Múlt-kor magazin: Az Ördög-árok legpokolibb tánca, August 2015.