First, a little context. These are residential

buildings from the late 1800s and early 1900s with two or three entrances and separate

addresses around inner Pest. Some accessible on foot, others by car.

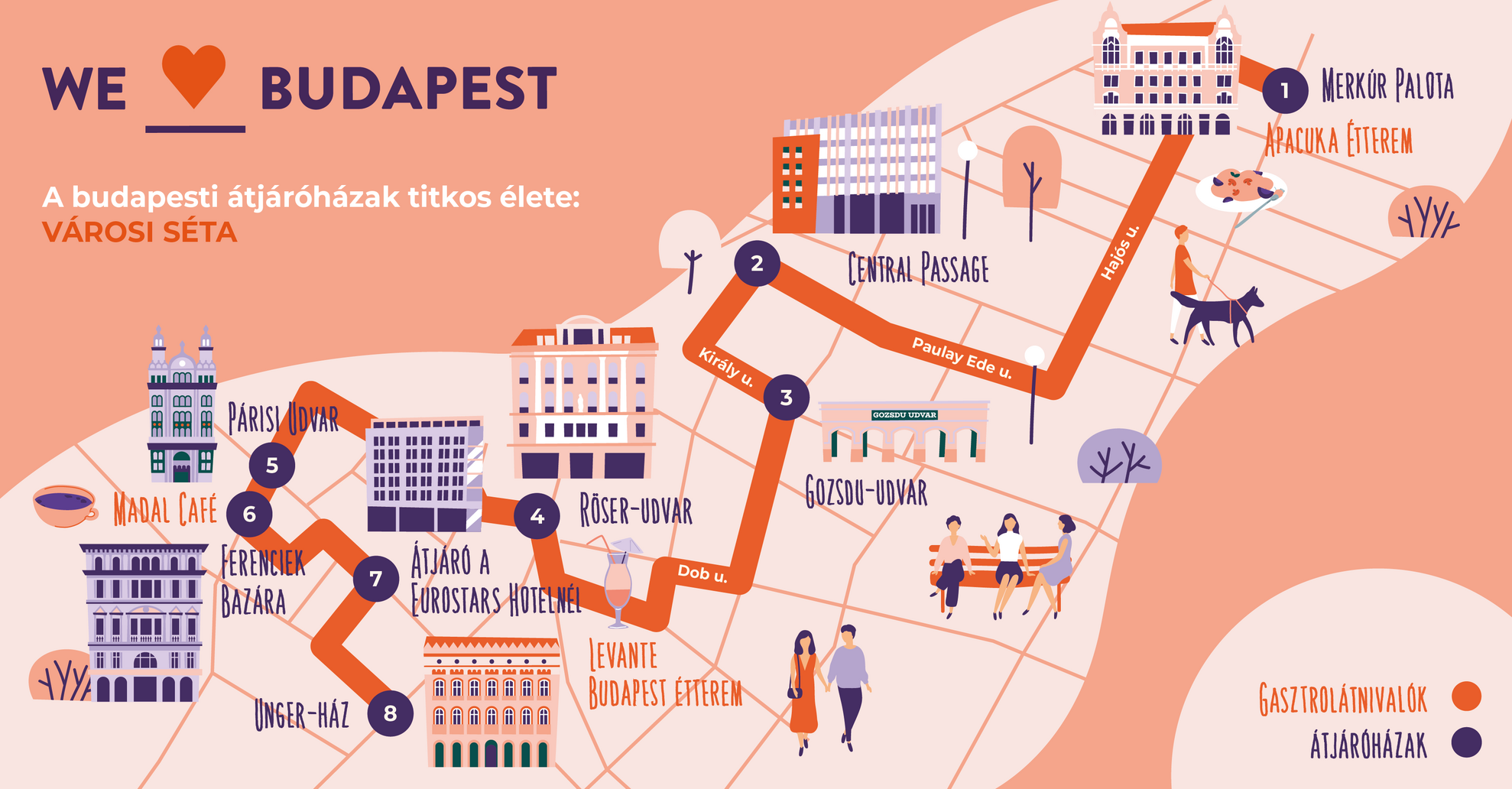

A map has

been provided with a simple graphic in Hungarian, orange dots for culinary

sights, dark blue ones for the points of interest themselves.

As you can see, our tour starts at Merkúr Palota on Nagymező utca and cuts through Districts VI and VII to finish at Unger-ház in the heart of town.

Today, these once manifold passageways are fewer

and fewer. Most have been gated off because of traffic or the building has been

converted into a hotel or offices, leaving only memories of its former

function.

Before they may have been provided busy artisans with working spaces

or shoppers with windows to browse.

Here are eight locations which survived urban

development – and look all the better for it. It might be worth scheduling your

jaunt on weekdays or Saturdays, because some houses may close on Sundays.

A hidden oasis on Nagymező

Turning away from the noise of Bajcsy-Zsilinszky út into Nagymező utca, you soon find yourself in front of the first building in the city specifically built as a telephone exchange. Today, this is the Merkur Palota (Nagymező utca 54-56), where our tour starts.

This slightly Art

Nouveau, slightly Historicist building, built in 1903, is a real treasure, as

its passage to Hajós utca is also where you find the garden of bright, summery

restaurant Apacuka.

Few actually know this passageway, however, its extravagant

courtyard, lined with lanterns, contemporary sculptures and glowing amber, is

the perfect place to for a coffee or delicious lemonade before setting off on your journey of discovery.

Where Napoleon hides

After Apacuka and the Merkúr Palota, you arrive at Hajós utca, where it’s worth first turning right and taking a look at several of the Art Nouveau houses covered with colourful flowers, almost at one end of the street. Floral Szedő-ház with a balcony was designed by Béla Málnai, and its stained-glass windows are most likely the work of legendary Miksa Róth.

The walk then

follows along Hajós (‘Sailor’) utca, named after the small pubs once frequented

by those who used to work on the Danube. Keep your mobile or camera ready, because

even if there isn’t another passageway here, there are more beautifully

renovated Art Nouveau buildings to see. Take a peek into the Napoleon

courtyard on the corner of Ó and Hajós utca, because behind the lovely

wrought-iron gate there is an even lovelier stained-glass door.

Although a

statue of Napoleon stands on the roof of the building designed by Gyula Fodor –

sadly long covered over - the house has much more to do with Napoleon III, the

last monarch of France, rather than the famous emperor born in Corsica.

Heading to the next passageway, have a look at the Corinthian columns of the residential houses and mansions, the figure of Atlas rising above the gateway, and the statues watching over passers-by.

After crossing Andrássy út, you turn right onto Paulay Ede utca, where you pass the late Art Nouveau building of the New Theatre as you approach the Central Passage.

The saga of Gozsdu Udvar

In the 1900s,

there were still three residential houses on the plots overlooking Paulay Ede

and Király utca. At Paulay Ede utca 3, where today’s Central Passage now opens, József

Zwack, founder of Hungarian national drink Unicum, lived.

There has been a car

park here since the 1970s, removed in the early 2000s to be replaced by a

270-apartment block and a business complex on the ground floor bisected by the

Central Passage. Wandering through its deserted glass spaces feels bizarre, although

if you scale the upper levels of the building you find a secret oasis full of greenery.

Stopping on Király utca itself, you find yourself opposite one of the back blocks of the Madách houses of clinker brick. To the left, Király utca is bereft of tourist bustle, allowing you to see just how many wonderful buildings can be found here. So often, locals prefer to take a parallel street to avoid the crowds.

Walking towards Gozsdu Udvar, you can admire the Classicist/Romantic braiding – the only surviving house in Pest of this type, with Art Nouveau on either side.

Gozsdu is Budapest’s most famous passageway, abandoned for decades, tied in the geo-political bureaucracy of having been commissioned by a Romanian lawyer, Emanoil Gojdu, who bequeathed his considerable wealth to local followers of the Romanian Orthodox Church.

After years of wrangling, renovation eventually took place in the early 2000s, the seven-courtyard corridor only bursting into life with bars and restaurants from around a decade ago.

A century ago,

this would have been the domain of street vendors, waited for trade beneath dim

arcades. At the Great Leftover Market, for example, women could buy clothing

and blouses for up to 20 crowns, but they didn’t have to go far to trade currency

either.

Some 200 metres long, this reinterpreted bazaar is not only the most frequented, but also the longest passageway in Pest.

Leaving Gozsdu, you can head to Röser Bazár on Károly körút via Wesselényi or Dob utca – if the former, you can pop in for Middle Eastern cuisine amid a Mediterranean atmosphere at Levante.

Downtown jewels

Röser Bazár is one

of Budapest’s nicest passageways, a conduit between the noisy boulevard and peaceful,

pretty Vitkovics Mihály utca.

The special feature of its Neo-Renaissance courtyard

is that it is one of the former bazaars that still has a function

today, the workshops of jewellers and shoemakers replaced by a

new-wave café, a lively breakfast spot and a designer shop.

Today, the twilight surrounding the courtyard feels romantic, but if you had lived in the 1920s, you may have had a different opinion. Passageways were ripe terrain for thieves. Unsuspecting citizens, under the pretext, say, of a cheap pocket watch, were lured to one of the alcoves and left to their fate.

These mysterious doorways also attracted secret lovers: the solitude of the arches and stairwells the ideal scenario for illicit romance.

From Röser Bazár,

a winding stroll takes past the Italianate shopfronts of Vitkovics Mihály utca to Petőfi Sándor utca, and the

beautifully renovated building of Párisi Udvar, adorned with hundreds of

thousands of Zsolnay tiles and ornamental decoration. The building, which also

housed a revered ice-cream parlour, was once a passageway house.

Brudern Bazár,

designed by Mihály Pollack of National Museum fame, once stood here, its

covered passages modelled after Paris, hence its name today. This house was

demolished in the early 1900s and was replaced by a palace designed by Henrik

Schmahl, known for its magnificent glass dome. For years it stood empty, dark

and devastated, until its recent renovation and rebirth as a Hyatt hotel.

It’s worth taking a small detour to walk down to Szervita tér, because a passage opens from Petőfi Sándor utca 14, characterised by its columns and the light filtering through the small domes.

If you’re in need of coffee, Madal on nearby Ferenciek tere should do nicely, its terrace sitting opposite your next destination. Ferenciek Bazár is an L-shaped gateway, accessible from Kossuth Lajos utca. It was built by Franciscan monks (hence Ferenciek tere) on the site of their damaged monastery, and the courtyard was once occupied by milliners, tailors, shoemakers and florists. Its shaded passage now houses a restaurant and secondhand shops.

Ignoring the passing traffic, you can nip down the small passageway of the Eurostars Hotel to find yourself among the eclectic buildings of Reáltanoda utca. This also brings you to the last, stop on the tour: Unger-ház.

This mansion

connecting Múzeum körut with Magyar utca is

one of the earliest works by renowned architect Miklós Ybl in Pest, and a real

cavalcade of styles, mixing Byzantine, Moorish, Neo-Gothic and Romantic.

You might

spot dragons on the façade nearest the körut, though

sadly, they’re in crumbling condition. The house is a listed building, and no

matter how convenient it might be to cut through here, its condition only deteriorates.