Alajos Hauszmann was the mastermind behind the New York Palace, the former Museum of Ethnography, the central building of the University of Technology and, above all, the reconstruction of Buda Castle in the 1890s. Despite the fact that he left a legacy of unique landmarks all over Budapest, the architect had a completely different career in mind throughout his childhood.

As a teenager, Hauszmann was much more enthusiastic about the world of chemistry and photography – and even theatrical art – than the mundane act of drawing up plans for buildings. Later in life, in fact Hauszmann founded a Hungarian-speaking theatre company with friends, and became its set designer, director and accountant rolled into one.

Few also know about the time when the young Hauszmann and companions miraculously survived a near-fatal boating accident on the Danube after a steamship struck and capsized their boat.

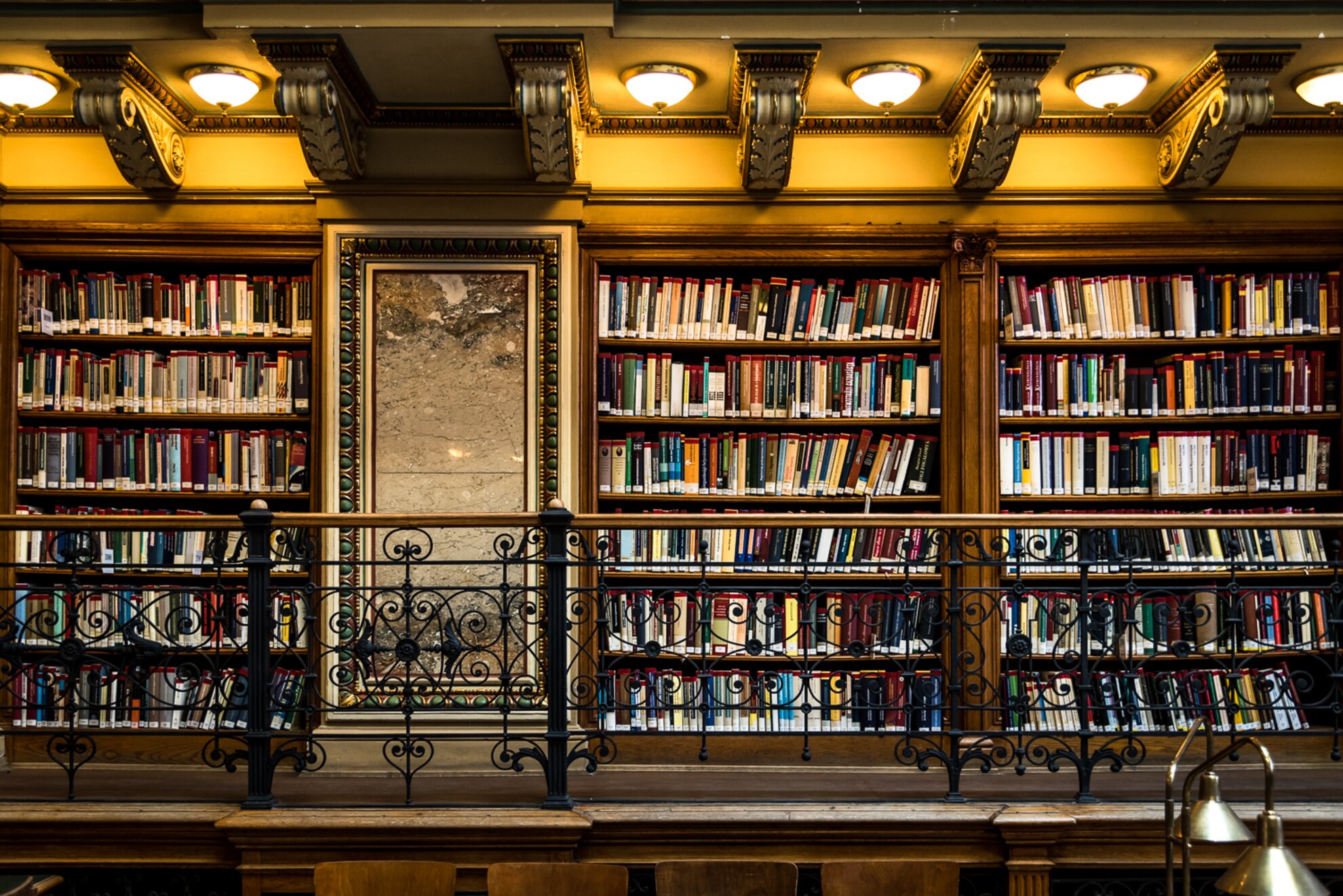

Hauszmann was an art student when Antal Szkalnitzky – architect of the ELTE University Library – discovered his talent upon seeing some of his drawings. He brought this gift for design to the attention of the young man’s father, and helped launch Hauszmann’s career.

When the Hungarian Academy of Sciences was still under construction, Hauszmann joined the team as a masonry apprentice to learn the ropes. Hauszmann’s later brilliant career was based upon his dedication and hard work over these early years.

The young man was filled with wanderlust: his journal gives enthusiastic and cheery accounts of his experiences and observations abroad. He travelled the whole of Italy and France, but Hauszmann also embarked on study trips to London, Munich, Amsterdam and Copenhagen, where he gained inspiration for the designs for Buda Castle.

His visits to Egypt and Palestine had a lasting impact on the well-travelled Hauszmann: lively cities in the East were filled with monumental buildings and cosmopolitan citizens driving modern cars, and he was eager to bring something of this atmosphere back home to Budapest.

In the 1880s, an international competition was held to find an architect for the new Hungarian Parliament building. Hauszmann emerged as one of the winners with his Renaissance-style design but the plans by Imre Steindl were similarly acknowledged and ultimately triumphant. Today’s Parliament showcases Steindl’s familiar Gothic-Revival style.

Hauszmann lost the battle but won the war: his architectural heritage still imbues Budapest in the form of private residences, mansions and significant public buildings. Standing opposite Parliament, the grandiose Palace of Justice, the later Museum of Ethnography, takes your breath away with its ornate façade and astonishing monumentality. The columns and tympanum inspired by Greek temples give an inkling of the pomp as you enter the main hall, its interior pervaded with Neo-Renaissance and Baroque characteristics.

Undoubtedly, the highlight of his career was when he was entrusted with the reconstruction of Buda Castle and the surrounding Castle Quarter in 1891, after the death of the renowned Miklós Ybl. Throughout Hauszmann’s 14 years as site architect, certain parties involved with Vienna’s imperial court frequently attempted to sabotage his work. Hauszmann struck back at them by paying personal visits to Franz Joseph, the emperor himself.

Even though Hauszmann’s artistic creativity was sometimes suppressed by the prevalent trends of style and social convention, he was always open to the implementation of new concepts and innovative materials. As a prominent figure in his profession, he believed that architecture should be authentic, practical and simple – even if his works were anything but simplistic.

In his study entitled A Few Words About Modern Architecture, he emphasised the importance of preserving tradition and welcoming change while creating new elements that embrace the past.

In light of his words, maybe we should give some thought to all these city development plans aiming to remodel and modernise Budapest. Are they all good examples of innovation? Will our society (and our environment) benefit from them? Are the architects creating something of value? All these questions give us plenty of food for thought, as we look ahead and not dwell on the past – even if certain things were indeed better back then.