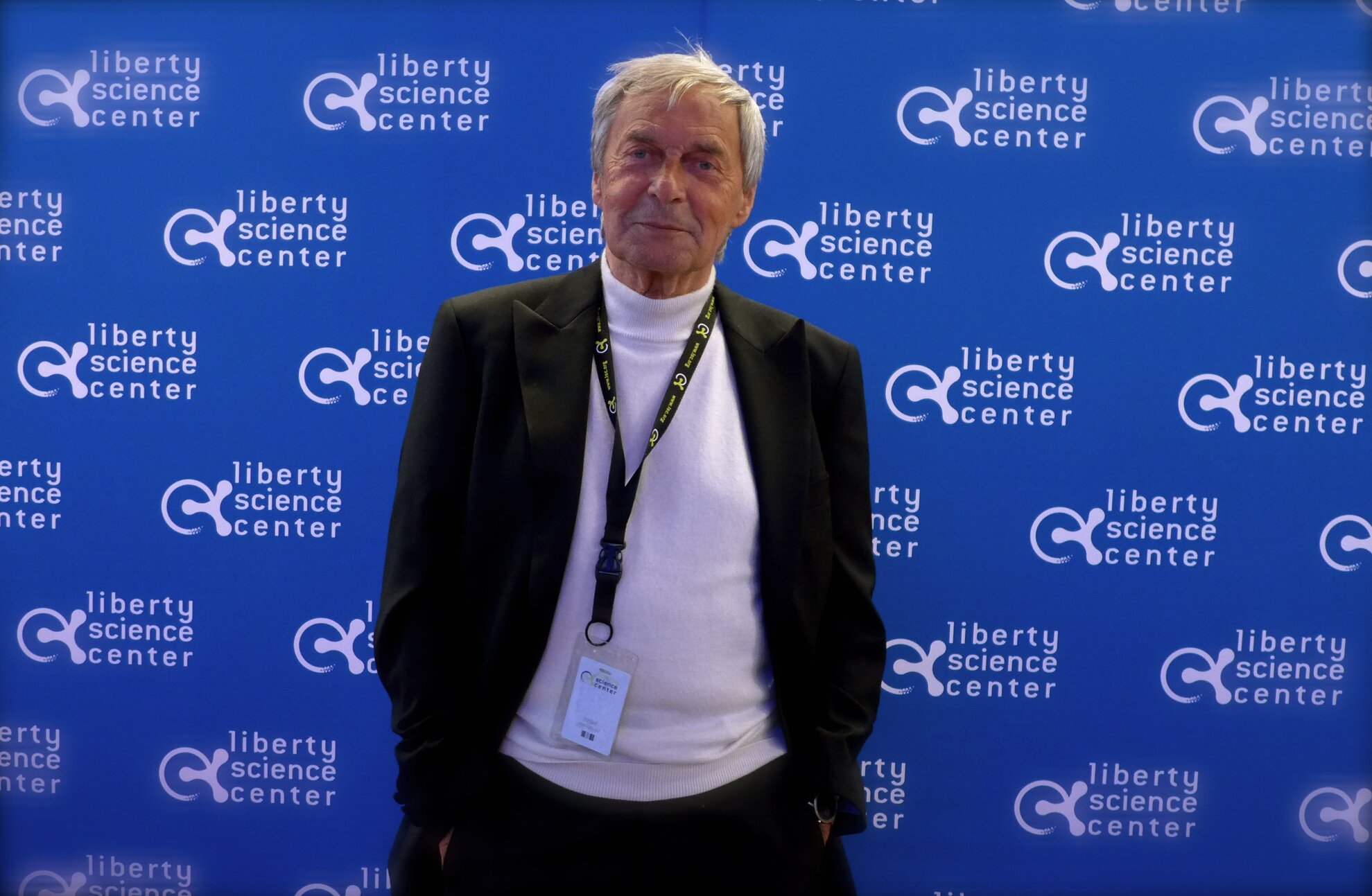

Perhaps the most famous Hungarian still alive today, inventor Ernő Rubik created his namesake Cube back in the 1970s. He details his remarkable story in a new book, ‘Cubed: The Puzzle of Us All’, written in English. It’s a journey that starts in wartime Budapest and continues with world fame, yet stays rooted in Hungary. We speak to the man behind the puzzle.

We Love Budapest: Why have you decided to write your book now, and why in English?

Ernő Rubik: I have reservations about writing and speaking in English, but I wanted a book that told the story of the mysterious existence of the Cube in the world, how I saw the background. When I started, I decided that the book would not have a traditional structure. Originally, I didn’t want there to be chapters in it either, I somehow imagined it would have neither a beginning nor an end.

Of course, in the real world, things don’t work that way. Now all I hope is to be able to trust the readers to decide how they think about its structure, and I trust they are smarter than I am.

It was important for the work to be created in English because the goal was for it to be read all over the world. It’s now two years since we agreed with an American and then a British publisher on this year’s release. Since then, a number of other territories have been signed up in other languages for Cubed: The Puzzle of Us All, which is available (or will be available) in Korean, Chinese, Russian, Italian and Spanish, among others.

WLB: In the book, you say that you felt you were born under a lucky star – this was Budapest, July 1944. Did your parents ever describe any of the hardships they almost certainly suffered in your first years?

ER: I was born almost exactly a month after the Normandy Landings, which marked the beginning of the end of the Nazi reign of terror and World War II. My father served somewhere on the front in the technical corps, while my mother was left alone with my sister when she was pregnant with me. Her family could no longer support her, her parents and her only brother had died in the war. When she went to work, she entrusted my sister to someone else. She said that I was one of the few new-borns who survived that hospital in Budapest during this terrible period – it was definitely a lucky start.

Designer dynasty

"After the war, my father’s successful factory, where they made gliders and kayaks, was nationalised. Interestingly, however, my father was able to stay there as an employee. He was an excellent, experienced professional, so he became responsible for everything: he was the engineer, the designer, the salesman, he even invented the names of the products and, in fact, often personally controlled the production process."

WLB: Some inventors say they became successful almost despite the education they received at school. How was yours?

ER: As a boy, I really enjoyed reading, and when I didn’t have to go to school, I had a lot more time for it. Once I felt determined, I learned relatively quickly and I definitely had a better memory than I do now.

When they’re studying, children need to feel good in themselves, they need to maintain their curiosity and their own motivation. Based on this, they can explore and get to know their world. The framework of school must not suppress the experience and freedom to question things on their own. I know it’s not easy, but I have heard of good examples.

WLB: From your original idea, how long did it take for you to reach something close to the finished product, the Rubik’s Cube?

ER: In the spring of 1974, my 30th birthday was approaching, and my room was like a schoolboy’s jacket pocket, full of all sorts of trash and treasure: scraps of paper, hard-to-read notes, drawings, pencils, crayons, bits of string, little sticks of wood, glue, tacks, springs, screws, rulers, on the shelves, on the floor and on my folding design table. They also hung from the ceiling, the door and the window frame. Among them were even a few cubes: paper, wood, monochrome, multi-coloured and solid cubes, and those consisting of smaller pieces.

The superficial observer might have thought I was preparing for my lessons, that I was figuring out what I was going to present to my students in class. That was indeed the case, but something else was happening as well.

Maybe six months after the Cube came into the world, I felt it was time to move up a level, to think about how to put it into production, because it immediately turned out that it wasn’t just me who found it interesting. Then I approached a patents lawyer. He asked me to make diagrams of the construction and its operation, and attach detailed descriptions. With his help, eventually the product was created.

In January 1975, I started the year by walking to the Hungarian Patents Office and filing a patent entitled the ‘Three-Dimensional Logic Game’. Finally, on 28 October 1976, the Hungarian patent was registered for the Cube. The first cautious order arrived in 1977, for 5,000 items.

WLB: How easy was it for someone in 1970s’ Hungary to make something incredibly successful in the West?

ER: In January 1980, I received my first blue passport. Hungary belonged to the Eastern Bloc and we could not travel freely. Most of us had a red passport with which we could only go to friendly Socialist nations. I had been to some Eastern European countries before, but trips to the West were out of the question. It required a blue passport that only a few people, mostly diplomats, were able to have at that time. In my childhood, it wasn’t so easy for someone to just travel to the West.

By the time I went to college, the situation was slightly relaxed, but we didn’t have the money for these kinds of trips, either. In those years, foreign trade was a state monopoly. Only official Hungarian companies dealing in foreign trade could be in contact with their Western counterparts. They handled all foreign trade, which mostly meant only imports from the West.

After signing an international distribution agreement with the Ideal Toy Company, I had to travel to the United States and other Western countries to present and explain the Cube to people there. So I handed in my ID photo and ID card to the authorities and I got my passport. As the Cube became popular, I travelled more and more.

WLB: From the Magic Cube to Rubik’s Cube – your name is known worldwide. Have you ever thought what it would have been like to have remained relatively anonymous?

ER: Anyone can be famous. But what does fame mean? That many people know or have heard of me, know what I did or what I didn’t do? It’s a paradox. My name seems to be known around half the world, but it’s as if that name is no longer related to me any more. The Cube has entered a narrow field of inventions named after their inventor. My name is interlinked to such an extent that its attachment to my person has virtually finished. I am thinking of things like the diesel engine (Rudolf Diesel), razor blades (King C. Gillette) or, known as biro in many languages, the ballpoint pen (László József Bíró).

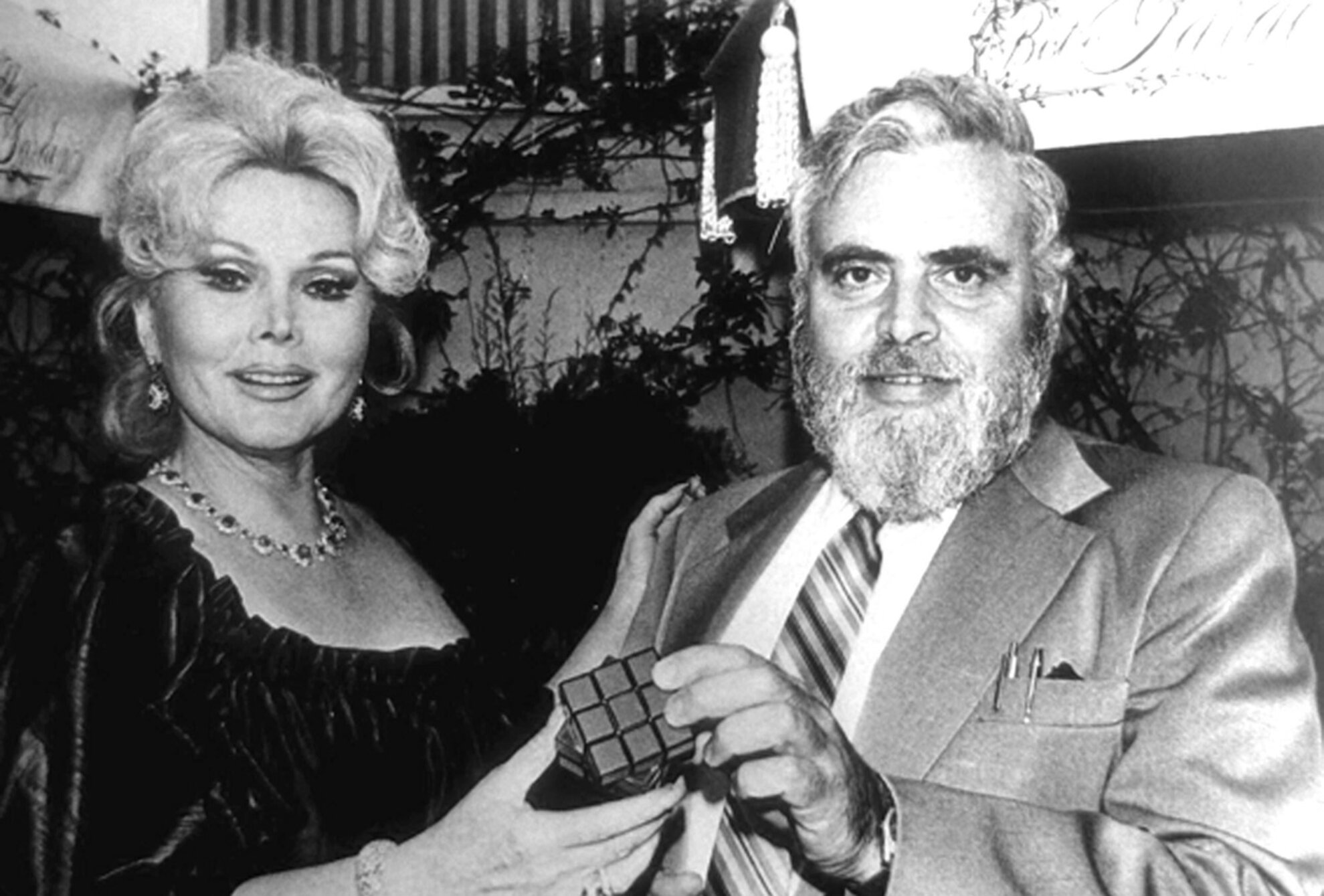

Garbo and Rubik

"Strange, but probably a lot of Cube fans have no idea that there was a guy named Rubik. Who, moreover, is still alive today, ‘Rubik the Cube man’. I’m always surprised to hear that some people want fame. Fame is something a person like me doesn’t ever look for. As the famous actress Greta Garbo said about fame, I prefer to stay behind the scenes."

WLB: Hungary is well known for its inventors. Why do you think this country produces so many of these pioneers?

ER: In the spirit of Kálmán Könyves, who famously once said, ‘There are no witches!’, I recently started a lecture with the words ‘There are no inventors!’ Their role can only be interpreted afterwards, when the inventor has already finished his work, and there is a working prototype on their desk or computer screen. Before any football match, we can’t say that a certain player is the goalscorer. To do that, they have to play first – and a little luck doesn’t hurt, either.

Hungary is justifiably proud of its great tradition in secondary education, from which world-renowned and leading researchers, artists, businessmen – and later inventors – have started out and carry on to this day. Perhaps our isolated language also enhances our creativity – we need to find our place in the world with accomplishments that can be easily understood by everyone.

WLB: You have always lived in Budapest and yet success would have allowed you to move anywhere in the world. Have you stayed here purely for family reasons or is there something else about the city?

ER: This is probably just my nature, others might have moved. There are those who do not need a home of their own, such as the famous mathematician Paul Erdős, who travelled the world with just a tiny suitcase and stayed with his other famous scientist colleagues for a few weeks or months. I need my home, my city, my friends, my family.

I have met many people who live in a country other than where they were born but did not actually find a new home. Settling down completely might be up to the second or third generation. So if I had gone, whether famous or unknown, I would definitely have remained a stranger in another country.

WLB: Do you think people will still be trying to figure out the Rubik’s Cube 100 years from now?

ER: The question is more how people will be 100 years from now. If they preserve certain traces of the past that we think of as good today, I think the Cube will have its place in that world, as well.

But it is certain that puzzles activate very important skills in all of us: concentration, curiosity, playfulness, the desire for a solution. These form the basis of all creative human activity. Puzzles aren’t just for fun or to kill time. Puzzles show us how to use our own creativity.

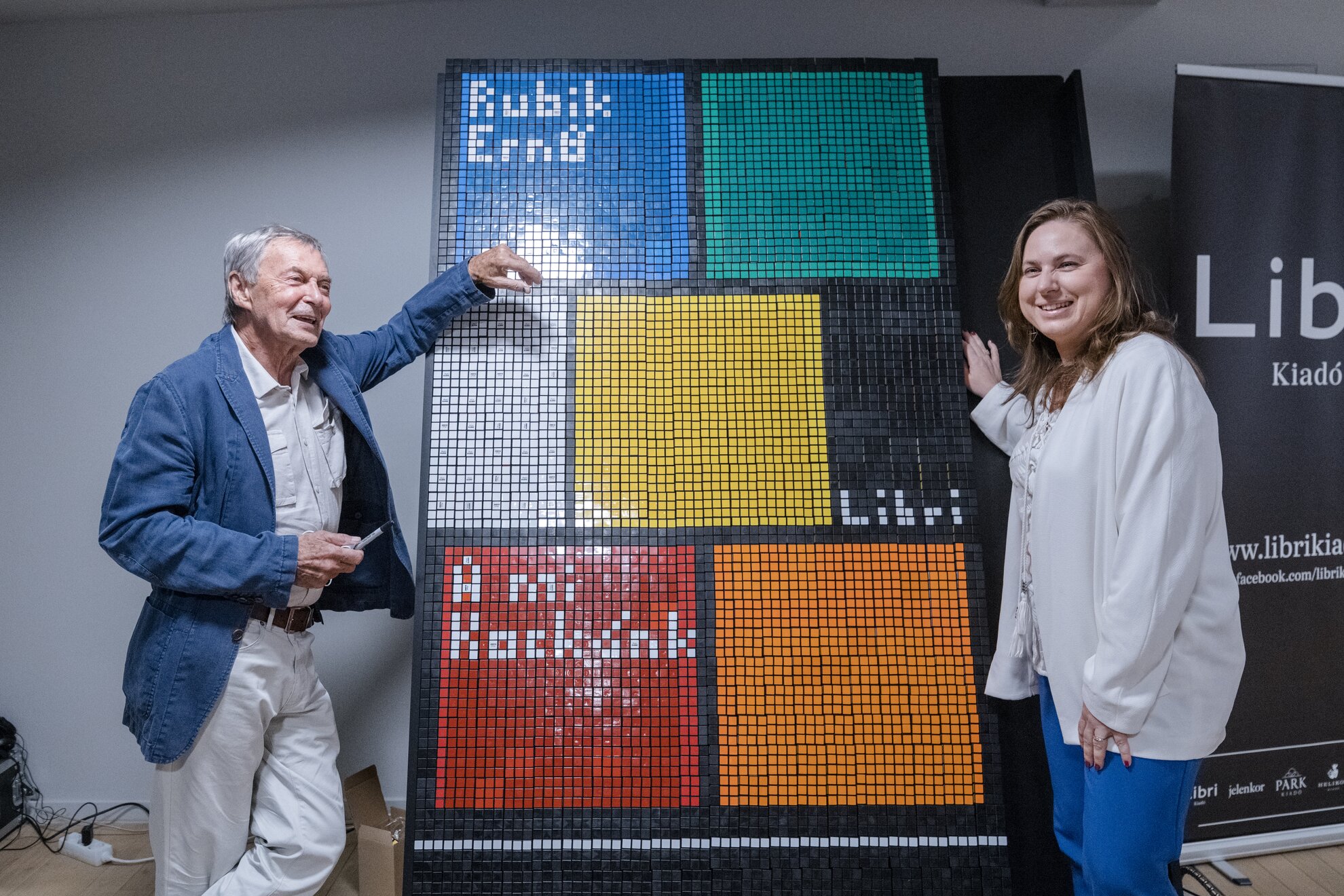

Cubed: The Puzzle of Us All by Ernő Rubik. UK edition (£14.99) by Orion Books, US edition ($25.99) by Flatiron Books.

Rubik Ernő, A mi kockánk, Hungarian edition (HUF 3,999/online HUF 3,799) by Libri.