Opened the same year that Mihály Kertész left Budapest for Hollywood to become Michael Curtiz in 1926, Budapest’s vintage Puskin cinema was the perfect setting for a special press screening of the latest Hungarian movie with a potentially high global profile.

Winner of Best Picture at the Montreal World Film Festival in 2018, Curtiz captures the same haunting aura as its progenitor, Casablanca, all plumes of cigarette smoke, dark interiors and stalking shadows. And yet, as its director, 32-year-old Yvan Tamás Topolánszky, tells us, it originated from long, early-morning journeys into the Hungarian countryside. “I was just starting out in the film industry,” he remembers, “and my job was to drive the actors from Budapest out to the set of Üvegtigris 3”.

With a cameo role in this somewhat jaded Hungarian comedy franchise, Ferenc Lengyel was one of Topolánszky’s passengers. “He started talking about this idea he had for a film,” says Lengyel, “and a couple of years later we met and he presented me with a photo of Michael Curtiz. It honestly looked like me!”

In between, the former gofer now aspiring director Topolánszky had formed his own company with his wife, Claudia Sümeghy, and was making short films. Casting around for ideas for his first big feature, he hit upon Curtiz. “He was a fascinating character,” says Topolánszky. “A man with all his faults. And it was also interesting to show audiences here how a famous Hungarian is perceived by the rest of the world.”

Just as the war influences how characters interact in Casablanca – the desperate bids to escape Nazi-occupied Europe, the promise of America, the everlasting themes of love and betrayal – so Michael Curtiz battles with his own conflicts. His sister is trapped in the Budapest Ghetto, his daughter shows up on set and his American wife is wise to his compulsive philandering.

While all these strands to the story are based on fact, the truth has been condensed and dramatised for it to make sense during Casablanca’s ten-week filming in the summer of ’42.

Curtiz, meanwhile, was shot in only 19 days, with a mainly rookie cast and crew. The movie’s star-crossed lovers Rick and Ilsa blend into the background as the spotlight focuses on the eccentric Curtiz, who made Bogie, famously shorter than Bergman, walk around on wooden blocks. His heavily accented English, with meaningless turns of phrase – “Devil Up!” he often exclaims, to no-one in particular – is also a matter of no little amusement. But Curtiz ruled with a rod of iron, the original cast, some of whom were actual European refugees anxious to stay in America, seemingly in perpetual fear on set.

“I was given a free hand to suggest lines and help mould the character,” reveals Lengyel. “I like to surprise the audience, to get a reaction to my action. Even just blurting out a phrase that is complete nonsense.” With more than 30 years of acting experience behind him, including a leading part in current Hungarian hit TV series Drága örökösök, not to mention his physical appearance, Lengyel slips into the Curtiz role with consummate ease.

We see how the tyrannical Budapest-born director not only had to battle with the consequences of his patchwork, prodigal past, but also with the war-time censor. “I love playing nemesis characters,” said Irish actor Declan Hannigan, cast as the sly Johnson, a thorn in the director’s side during the filming. “They’re much more interesting!”

With the revered closing airport scene – much of Casablanca, in fact – only conjured up on set, Curtiz was under constant pressure to deliver a film that gave people hope in the darkest days of World War II, partly for it to act as a recruitment drive in America. And hope, like fidelity, was in short supply. “When I read the script, I found a lot of parallels with the world we’re living in today,” says Hannigan, perhaps nodding to the ‘Make America Great Again’ reference that elicited a communal chuckle at the Puskin screening.

A long-term resident of Budapest, Hannigan has also just written his own first series for Hungarian TV, A Hentes, about strange goings-on in a local village, due to air this autumn.

Apart from the fraught discussions between Curtiz and his Hungarian compatriots – for which English subtitles are provided – the dialogue is in quick-fire 1940s’ English. Crafted by Ward Parry, formerly of entertainment giants Legendary and The Guardian newspaper, the script is the result of incessant skyping between Parry in North America and the director in Budapest. “Ironically, the first time we met was after the film had won top prize in Montreal,” says Topolánszky, “and it was laughs and hugs all round”.

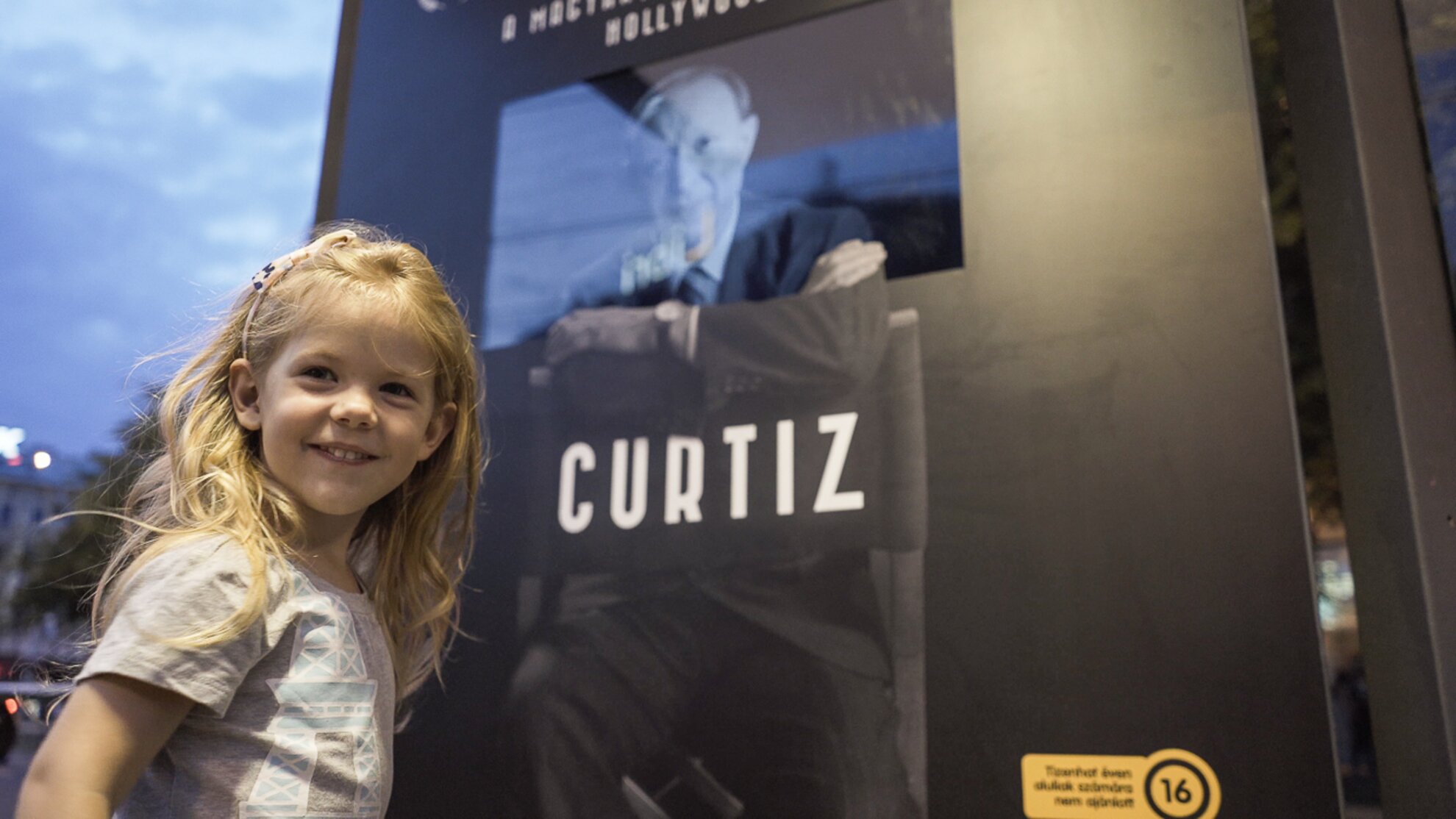

With a blue-chip subject matter, great things are expected of Curtiz once it gets global distribution, a deal currently on the table. As for Budapest, the film is showing across the city from Wednesday, 12 September. A unique PR campaign at the tram stop by Nyugati station allows passers-by to interact with Curtiz/Ferenc Lengyel himself as he attempts to find actors for his upcoming ‘movie’.

As for Topolánszky, he has been researching hard for his next projects, a Sci-Fi picture set in Budapest, and a short film about the border between the USA and Mexico. Even Curtiz, who had himself thrown in jail for a week before making his first Hollywood feature about Chicago gangsters, might have approved.

Curtiz, showing from 12 September around Budapest.