Documented by large text signboards, most with English translations, the exhibition covers in considerable and wide-ranging visual detail the six-year history of what was then the only regular venue for alternative music, and alternative people, in Budapest.

Co-curator Lóránd Balla, himself a Lyuk regular back in the day, takes up the story: ‘Alternative Hungarian band Balkán FuTourist played the Rote Fabrik in Zürich in 1987. They soon realised that this was just the kind of centre for underground culture that Budapest needed’.

An offshoot of legendary group Kontroll Csoport, whose frontman Péter Müller created the Sziget Festival, Balkán FuTourist later starred in a French-made video about the scene here.

‘Foreigners really wanted to know about underground culture on this side of the Berlin Wall,’ remembers Balla. ‘Western punk bands Nomeansno, the Dog Faced Hermans and Fugazi came to play the Fekete Lyuk more out of curiosity than anything else. It certainly wasn’t for the money.’

In all, some 650 bands performed at this dark cellar club tucked away on aptly named Golgota utca in a forbidding nook of run-down District VIII.

The Fekete Lyuk opened in April 1988, an era, referred to here as the ‘contradictory climate of the 1980s’, when Communist control was still in place but the cracks were beginning to show. The Lyuk was not only where punks got drunk but a meeting place for anti-government resisters, ironically including later key members of what is Hungary’s ruling party today.

‘Club manager Gyula Nagy saw the Lyuk as the one destination where everyone from all strands of alternative life in Budapest could go,’ explains Balla, in praise of his co-curator who passed away shortly before this exhibition opened. ‘Gyula liaised with the authorities, making sure that no-one would be hassled once they were inside. On the other hand, the police knew that all those they needed to keep an eye on would be gathered here.’

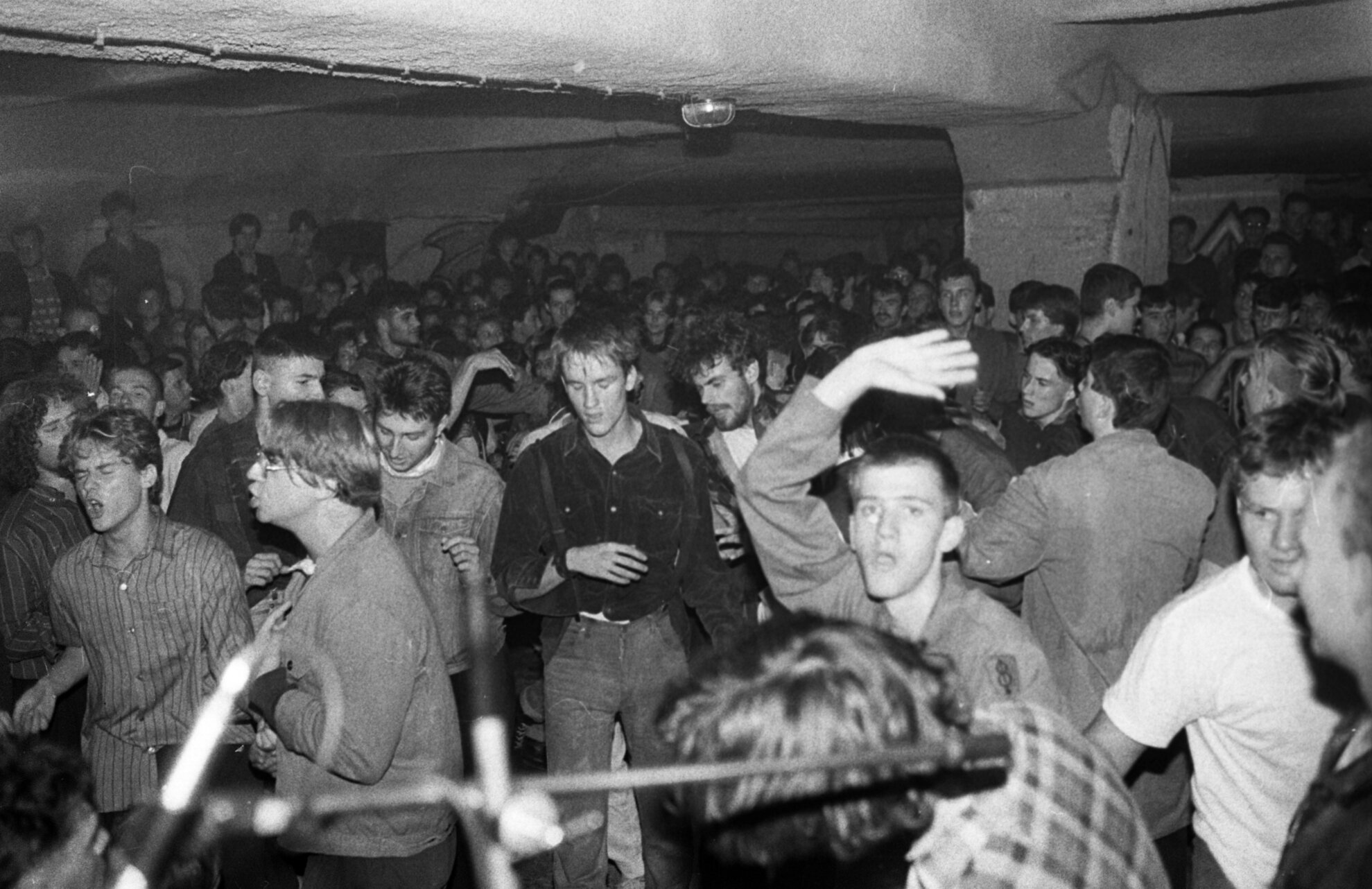

So what was the Fekete Lyuk like? The very layout of the exhibition, around a winding, chilly cellar (keep your coat on when you visit), echoes the legendary club of yore. Posters, flyers, photographs and a glass case of cassettes indicate the regular agenda here, bands such as Leukémia, Hisztéria and Aurora thrashing out a ferocious noise to a sweaty young throng.

It wasn’t all three chords, though. As the exhibition reveals, the Lyuk staged the plays of local troupe Független Színpad, housed the studio where Feró Nagy presented his influential radio show Garázs, and hosted a fashion show by pioneering designer Tamás Király, who wowed Vivienne Westwood with his radical outfits as showcased at a Berlin railway station that same year of 1988. The Lyuk even had its own samizdat publication, Lyukság (‘Holeness’), with a print run of 1,200.

Szolnok-based company Inconnu Csapat linked with the Lyuk to create political actions, such as the one by Plot 301 of Budapest’s New Public Cemetery, the clandestine grave of Imre Nagy. The reburial in June 1989 of this leader of the 1956 Uprising proved to be the high-water mark of Hungary’s anti-Communist wave. Once the Wall came down five months later, Lyuk regulars no longer had anything to kick against.

Broadcast from a bank of TVs, a series of interviews with the leading protagonists of the day – Lyuk staff such as the former bouncer, barman and DJ, plus all the usual suspects, punk-wise – looks back on the Lyuk of 30 years ago. Ace face Zoltán Bajtai (aka Barangó – everyone was an aka back then, Diana, Kalapos, Pálinkás, and so on) describes a seminal moment when a political agitator tried in vain to rally the Lyuk crowd towards a more focused form of protest. ‘Look!,’ someone shouted back from the mosh pit, ‘we’re just punks. Nothing more. We come here to get drunk, that’s all we do. Don’t expect anything else from us’.

Not only had the club lost its raison d’être, by then it had local competition. Sensing a gap in the market, the authorities opened the Petőfi Csarnok concert hall in the City Park, where the bigger alternative bands of the day, such as VHK and Európa Kiadó, could play. Both are still active, the former playing at this week’s opening ceremony of the exhibition, the latter at the A38 Ship before this New Year’s Eve.

One of the last displays here shows a series of Lyuk-related newspaper articles, one from the former local red top, Mai Nap, from 1994, in which Gyula Nagy is shown trying to get back into his club using bolt cutters. ‘Fekete Lyuk bezárlyuk’ runs the punnish headline, ‘Black Hole holed!’

Bizarrely, some of the filmed interviews for this exhibition took place at the same venue, now called the Fehér Lyuk (‘White Hole’) and run by Christian pensioners. Friendly old ladies opened the door to welcome some of Budapest’s most radical faces from 30 years ago.

When Nagy and Lóránd Balla dreamed up this exhibition, contacting a Facebook group of some 3,500 followers, they little expected the thousands of photographs and posters that flooded in. ‘What you see here,’ says Kiscelli PR manager Miklós Tömör, ‘is just the tip of the iceberg’.

With so much enthusiasm for the project and so much material, spring will see a series of live shows in the Kiscelli courtyard, round-table discussions and, potentially, an archive catalogue. Who knows? Maybe punk’s not dead after all.

Fekete Lyuk – Underground Budapest ’88-’94

Until 23 June 2019

Open: Tue-Fri 10am-4pm, Sat-Sun 10am-6pm. From 1 Mar: Tue-Sun 10am-6pm

Kiscelli Museum District III. Kiscelli utca 108 Admission 1,200-1,600 forints