As autumn paints countryside villages with patches of orange, brown and yellow, families gather around tables full of harvest-season specialities around a succulently roast bird. This may seem like a description of America’s cherished Thanksgiving feasts, but it also depicts another seasonal celebration dating back hundreds of years before Europeans discovered the New World: St Martin’s Day. Observed every 11 November around Europe, it holds special significance in Hungary, whose borders encompass the birthplace of this significant saint.

Most commonly honoured as the patron saint of beggars, St Martin was renowned for his kindness, calm and modesty. He became prominent across Gaul (modern-day France) as the Bishop of Tours, he established monastic traditions that persist to this day, and was one of history’s first conscientious objectors.

Yet St Martin shunned public adoration, and spent much of his life as a hermit in the wilderness. Nonetheless, this humble holy man is now revered in Hungary and around the world, especially when his feast day of 11 November provides an eagerly anticipated occasion to devour delicious goose dishes – and try the year’s new wines.

Born around AD 316 in Hungary’s oldest city of Szombathely, known as Savaria in the Ancient Roman province of Pannonia, Martin was the son of a military tribune who moved his family to Pavia, Italy. Here, Martin grew up to follow his father’s footsteps by joining the Roman army, although at a young age he was already touched by the Christian beliefs embraced by Emperor Constantine.

Thus, when Martin’s regiment was sent to Amiens in Gaul, and the young soldier spotted a shivering beggar dressed only in rags at the city gates, Martin used his sword to cut his own woollen cape in two so that he could give half of it to the poor man. That night, Martin had a dream revealing that the beggar was actually Jesus, and from then on, the future saint devoted his life to God’s works.

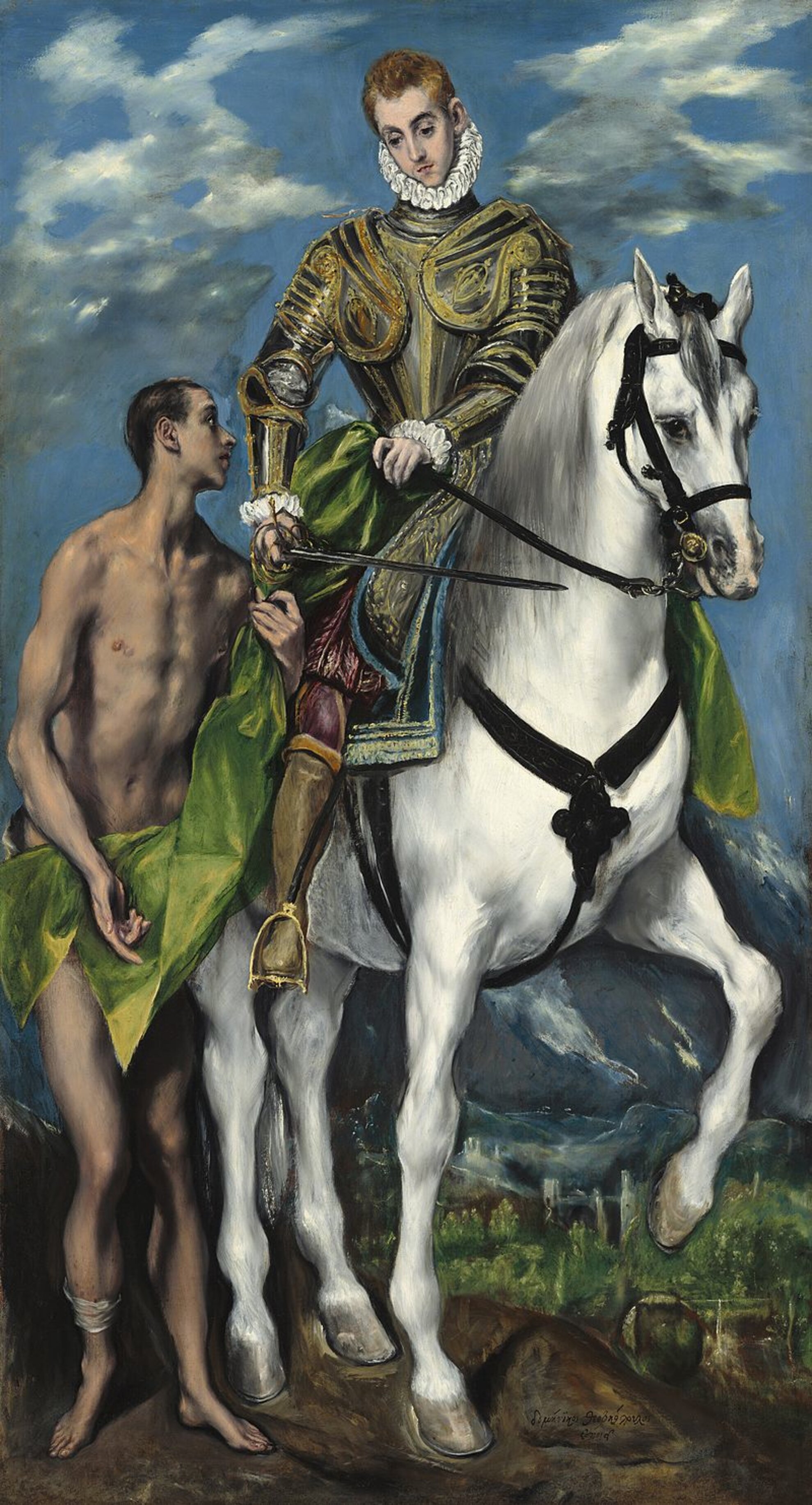

Martin’s selfless act of offering a swathe of the garment off his own back earned widespread acclaim – it is a scene depicted by El Greco, Louis-Anselme Longa and many other notable artists – but this was far from his only good deed.

Later in his military career, just before a battle in a Gallic province, Martin decided that he could no longer participate in Earthly wars, stating, “I am the soldier of Christ; it is not lawful for me to fight”. This type of non-violent declaration was a revolutionary affront in the Roman Empire, and Martin was charged with cowardice and imprisoned.

In response to the charge, he volunteered to join the front line completely unarmed. His officers were eager to take him up on this offer, but then – perhaps thanks to divine intervention – the enemy forces appealed for peace, the battle was called off and Martin was released from military service to join the priesthood.

In the following years, Martin embarked on evangelical voyages taking him to several European regions, beginning in Tours before crossing the Alps to Milan and then back to Pannonia.

After encountering occasionally fervent resistance to his Christian messages, Martin took refuge on the tiny island of Gallinara by the Mediterranean coast between Nice and Genoa, where he began living as a hermit.

However, his Godly calling eventually brought him back to Gaul, where he established the Benedictine Ligugé Abbey – one of Europe’s oldest monasteries, which still serves as a holy site today.

About a decade later, although Martin enjoyed the quiet life of a monk, the regional congregation decided that he should become the next Bishop of Tours – but how would they convince him to take the socially prominent post? According to legend, community members devised a ruse. They first drew Martin to Tours by claiming he was needed to minister for a sick person and brought him to the church, where he was appealed upon by the masses to become the new bishop.

At first Martin suffered a panic attack and ran away from the church to hide in a goose pen – but the loud waterfowl started honking, giving away Martin’s hiding place, and so the reluctant cleric accepted his fate and took the bishopric post.

Martin continued his holy career for many more years, performing several miracles before his death in AD 397. His legacy reverberates throughout European history to this day with many tales of his being an exemplar of humility and generosity… yet it was Martin’s predicament in the goose pen that established his most famous cultural association, the tradition to eat goose dishes on his feast day of 11 November – a custom observed so faithfully in Hungary that an old saying here goes, “One who does not eat goose on this day remains hungry throughout the year”.

Fortunately, autumn is when the growing flocks of geese need to be culled anyway, so since the Middle Ages, families across Hungary happily take this opportunity to gather around a roast bird every St Martin’s Day, either at home or in restaurants.

Coincidentally (or maybe not), St Martin’s Day also falls around when the grape yields of the harvest season can be enjoyed as new wines, so this holy occasion is also revered for the opportunity to try the latest yield of Hungary’s good libations.

This is how this saint earned the nickname of the 'judge of new wine'. St Martin is also considered a patron of winemakers, as well as soldiers, geese and France.

Nowadays, in addition to private gatherings of family and friends to feast on all kinds of goose specialities and drink the latest wines, public celebrations draw festive crowds to honour St Martin across Budapest and Hungary.

One of the country’s most historically fascinating events takes place at the open-air Skanzen Museum in Szentendre north of Budapest. Here, visitors can see traditional folk-dance performances and savour goose-based culinary delights, or watch women in customary Hungarian outfits pluck goose feathers to make handcrafted bedding and decorations, a St Martin’s Day activity dating back many centuries. This year's festivities take place on 13-14 November.