World War I left Budapest drained of its economical, financial, and human resources. Soon afterwards, slums started to develop in District IX and District X. With small, ramshackle houses and makeshift huts made from garbage, the situation became so out of hand that something had to be done. The “building complex” on the corner of Illatos and Gubacsi Roads was built as a social-policy initiative. The three- or four-story residential blocks had 426 apartments. The selection process was difficult, as getting an apartment in 1937 was a real privilege. The first ones to receive a home were the highly disadvantaged families with many children, with at least one member already working in Budapest. If there were fewer children, two families had to share an apartment. Usually eight or nine people lived together in apartments as small as 28 square meters. During 1939-40, the number of residents in these buildings reached 4,000. Many people moved in because of their impossible living conditions, hoping for a better, brighter future.

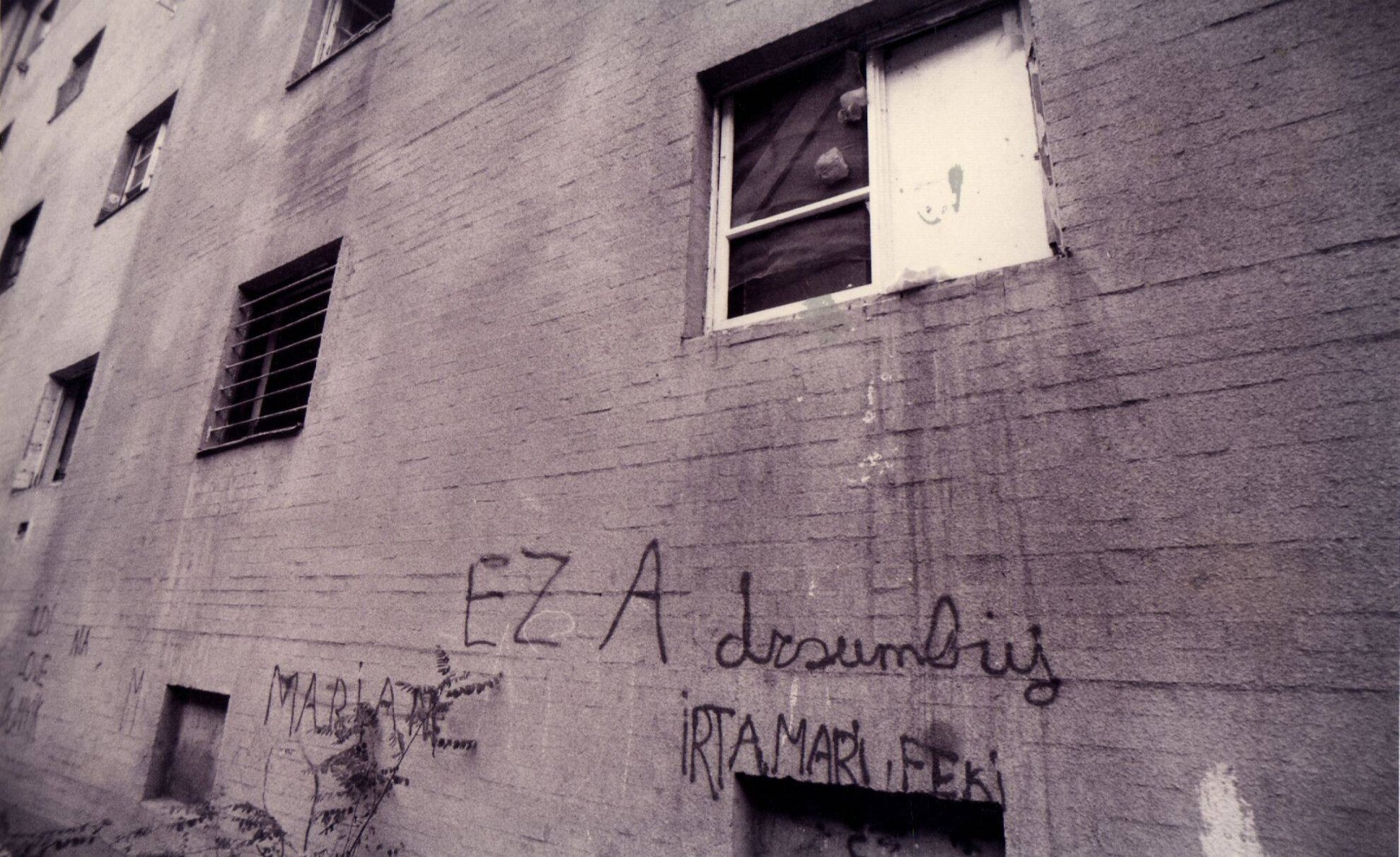

These poor but mostly upstanding residents became outcasts, a discriminated and belittled group that was called the “dzsumbujisták” (the residents of the Dzsumbuj). Due to their dire social and housing situation, they developed their own set of rules and norms, which was completely different from that of the outside world – meaning the rest of Budapest, which was a great unknown to many Dzsumbuj residents who never set foot outside of their slum. A book by Péter Ambrus titled A Dzsumbuj (The Dzsumbuj) vividly describes the everyday lives of the residents, their families, their utter despair, and their hopes. He tells the story of this place that was meant to exist for only 25 years, but survived World War II, the Soviet era, and the regime change, only to be finally demolished in 2014 after a ten-year-long period of liquidation.

A photo exhibition at Budapest Pont showed the personal stories and portraits of former residents of the infamous block. The volunteers of the

A város peremén project didn’t have an easy job when trying to search for the families that were displaced from Illatos Road, but fortunately they were able to conduct interviews with many former inhabitants, so that they could find out what life was really like at Dzsumbuj. Many of them were there at the opening ceremony of the exhibition.

We also saw Simon Szabó’s award-winning short film titled A fal (meaning “The Wall”), which provides a glimpse into the life of a Roma boy in 11 minutes – he takes odd jobs, and he’s currently building a wall on the grounds of the former Dzsumbuj; a wall that separates the Romanis from the rest of the city.

Both the film and the “Dzsumbuj phenomenon” are thought-provoking; the

A város peremén project is a great initiative, and they will continue their work by looking into other parts of the city. They also have a tumblr page, where they share short stories about people who lived at the Dzsumbuj, or visited the Illatos Road blocks. These stories are bittersweet – just like the story of this slum that existed from 1937 to 2014.