After seven decades of nearly uninterrupted existence, the Hungarian forint is the country’s longest-circulating currency.

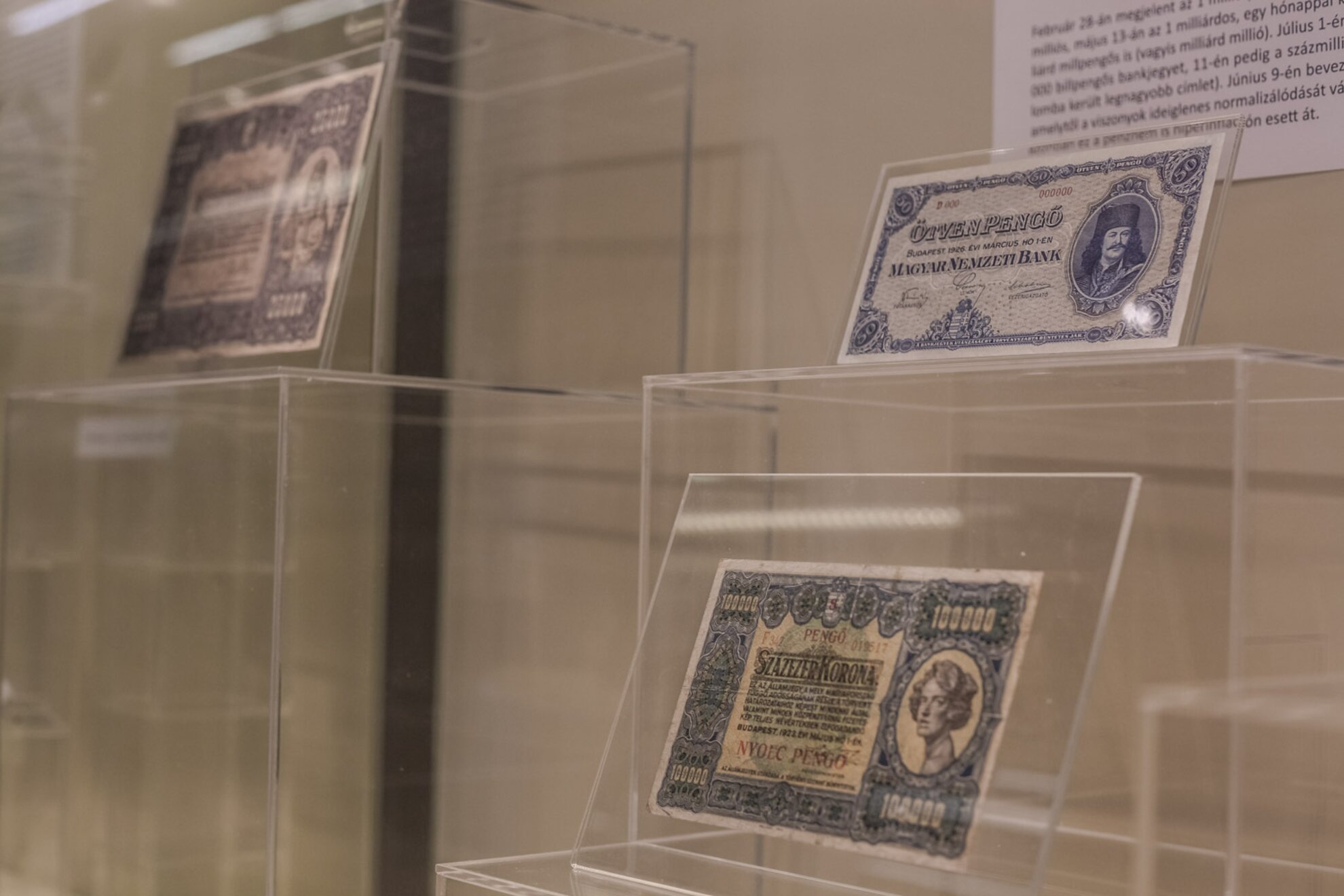

The name “forint” – a term deriving from the city of Florence, where golden coins were minted beginning in the 13th century – was already in use in 1325 as a reference to Hungary’s golden coins, and later when referring to the country’s silver coinage. In 1892, the Austro-Hungarian Empire introduced the “korona” as an official currency, but this joint money experienced severe impairment during World War I, precipitating its withdrawal from the market in 1927, when it was replaced by a novel Magyar currency, the Hungarian pengő. This new financial unit was introduced by the freshly founded Central Bank of Hungary as part of efforts to stabilize the country’s economy, but when Hungary went on to sustain severe damage during World War II, this caused massive hyperinflation of the pengő.

To counterbalance the deep economic crisis that the country was enduring, the post-war government introduced the Hungarian forint in 1946 as a gold-based currency. This new form of legal tender enjoyed a relatively stable position until the early 1980s, when inflation began to increase, and after the 1989 fall of the communist regime, the forint’s value continued deteriorating at a faster rate. (Until 1999, the forint was subdivided into 100 fillér coins, but due to the inflation, fillér coins are no longer in circulation, even though the denomination is still used in some price calculations.) However, as Hungary became more established as an independent nation and joined the European Union, the country's economy became more stable, and the forint gained stability as well.

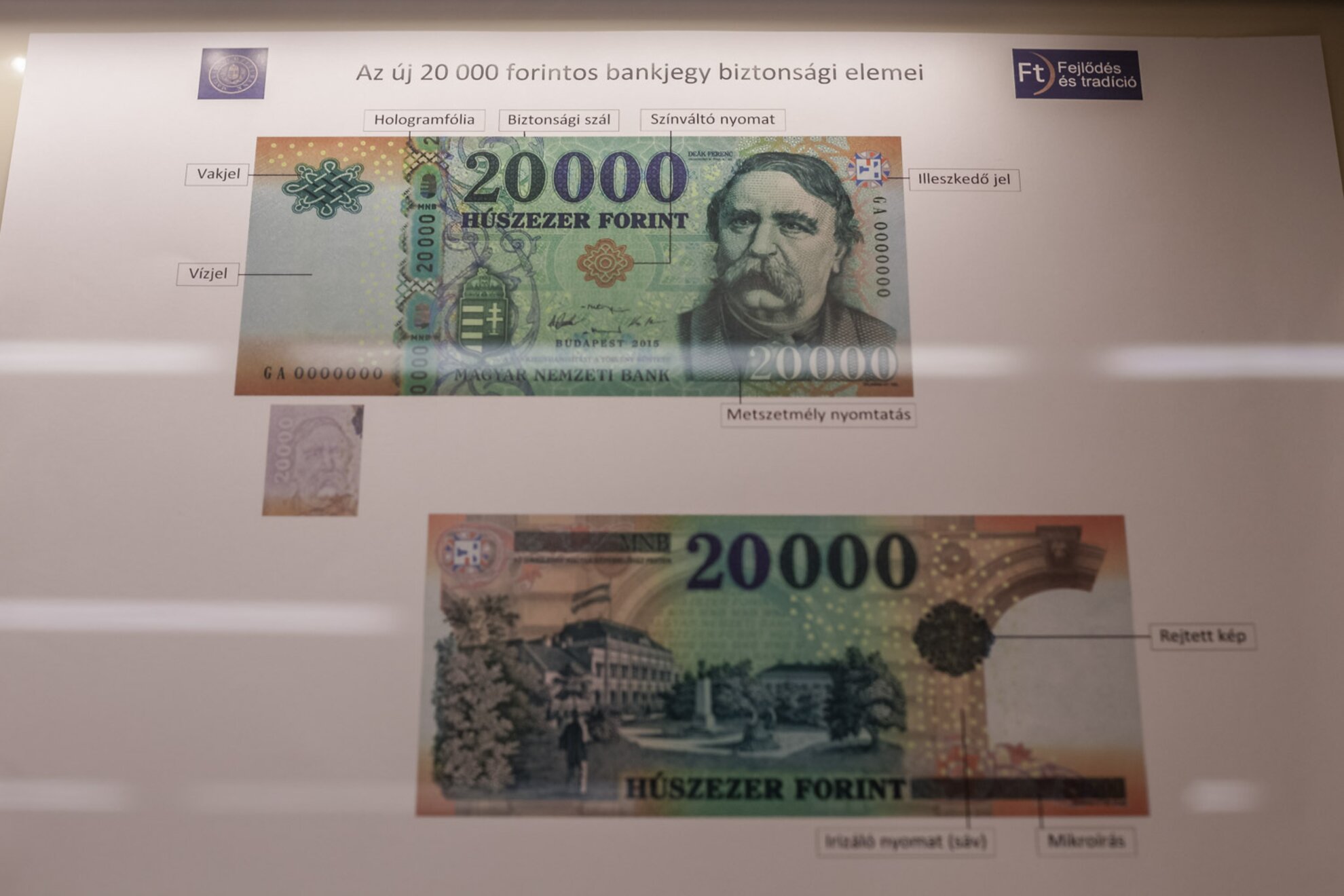

Today, forint coins are circulated in denominations of 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, and 200, with each one depicting an important Hungarian symbol, including the country’s coat of arms and the Chain Bridge. Modern-day forint banknotes – in values of 500, 1,000, 2,000, 5,000, 10,000, and 20,000 – portray historic Hungarian leaders on the front side (like the founder of the Hungarian State, King St. Stephen, or renowned aristocrat István Széchenyi), while the back side of each bill presents places or events related to the illustrated national heroes.Those who would like to learn more about Hungary’s currency can visit a free temporary exhibition at the Corvinus University of Budapest inside the school’s building “C” (Budapest 1094, Közraktár utca 4-6), open on weekdays between 10am-6pm, to showcase the history of the forint. Inside this modern wing of the university, the entrance hall holds a lengthy series of illuminated glass-covered cabinets that present the evolution of the Hungarian forint. Artifacts of legal tender on display begin with splendid pre-forint golden and silver coins in varied forms and sizes, followed by oversized korona bills and a collection of pengő notes in unusually high denominations, before continuing with well-preserved forint and fillér money from when it was first introduced into the country. This retrospective intriguingly captures the currency’s transformation over the decades, as smaller denominations became obsolete, forint coins in lower values were eliminated, and some of the smaller denominations that were formerly printed on banknotes were replaced by coins. Several displays inspire nostalgic feelings – especially for local visitors – by presenting now-antiquated forint coins and paper bills presented beside current currency.Beyond showcasing the forint’s development, this monetary display includes a wealth of commemorative coins that were issued during the currency’s history in different sizes, shapes, and denominations, with this expansive collection including such treasures as the square-shaped coin honoring Hungary’s renowned Rubik’s Cube, or the wavy-edged coin picturing Budapest’s Dohány Street Synagogue. Commemorative coins were also issued to observe the 1848 Hungarian Revolution, or honoring major sports events like the Football World Championship in 1982, but several of the metal treasures depict historic Hungarian characters, like world-famous composer Ferenc Liszt, or the Impressionist painter István Csók.Inside the final showcase of the exhibition, visitors get a detailed depiction of the various elements that are used to secure banknotes against counterfeiting. Here, besides observing all of the security components that are applied when printing paper money – including watermarks, vertical security strips, and hologram foils – we learn that only designated artists are entitled to work on designing new banknotes, who have profound knowledge of the applied security components, and the required printing techniques. The exhibition is complete with interactive boards presenting detailed descriptions about the story of Hungary’s currencies (soon to be displayed in English, as well), while a few mini movies provide entertaining insight into the past decades of the forint and its predecessors, with most of these films available with English subtitles.

After viewing the exhibition, anyone who would like to possess a piece of Hungary's monetary history can head to some of Budapest's antique shops to purchase decommissioned bills and coins: Antik Bazár in District VII near Blaha Square (Budapest 1071, Klauzál utca 1) literally has a pile of old Hungarian cash dating back to the 1940s, with every bill on sale for 300 forints.

Furthermore, outdated forint coins can be found at PeCsa’s weekend flea market (Budapest 1146, Zichy Mihály út 14), which are sold among myriad other Magyar antiques.

Looking ahead, as Hungary is a member state of the European Union, the days of the Hungarian forint might be numbered, because in the future the Magyar money may be replaced by the euro, the official currency used across the Eurozone. But whether or not the euro will be introduced into the country, the Hungarian forint will always hold a special place in our hearts (and wallets) with all of the national heroes and local landmarks depicted on each banknote.