The 1910s and 1920s in Russia and Soviet Russia not only brought about revolutionary changes in politics and public life, but also within the branches of the country’s varied art world. Avant-garde was the prevailing art movement of the time, and one of the oldest and most unified collections of art objects dating back to this period can be found in Ekaterinburg. The Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest’s scenic Royal Palace is now launching a very significant exhibition, showcasing pieces from this versatile display of unconventional artworks, which have never left Russia until now.

The grand exhibit features 40 outstanding artworks by such notable visionaries as Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky, Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, Natalia Goncharova, and Mikhail Larionov. But how did all these fantastic creations end up in a state museum?

The answer lies in the reorganization of Russian cultural life after the Bolshevik Revolution: in 1918 the Moscow-based arts department of the People’s Commissariat for Education approved a list of names, including prominent artists, whose works would be collected for a large-scale display titled “All the Movements of Contemporary Painting”. This massive collection would later comprise a huge part of the works now held at Russia’s Ekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts.

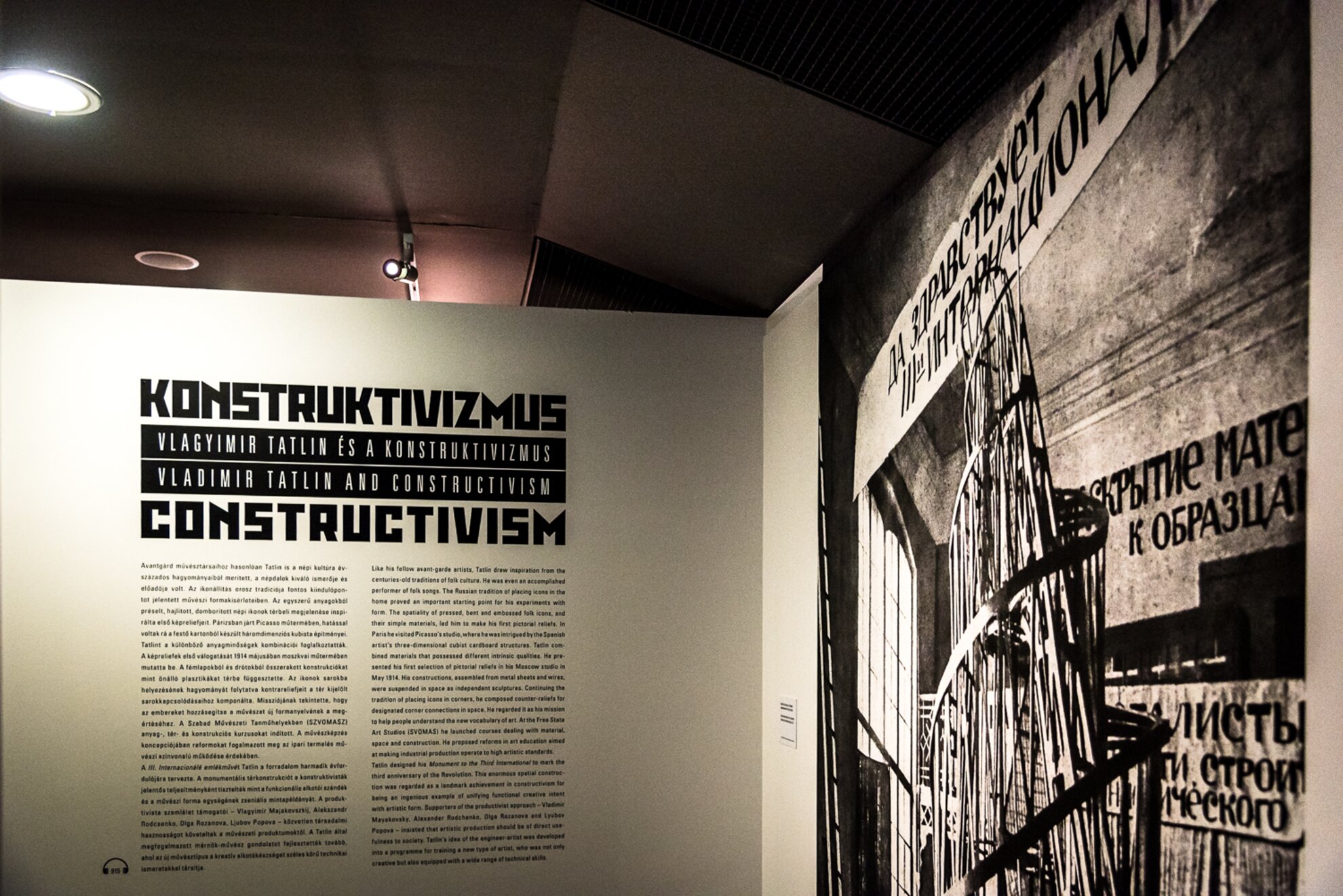

The Budapest exhibition explores the history of Russian avant-garde through five major themes, namely neo-Primitivism; the Jack of Diamonds art group (1910-1917); Cubism, Futurism, and Cubo-Futurism; Suprematism; and Constructivism. Strolling through the National Gallery’s exhibition halls on the third floor, visitors gain considerable insight into early-20th-century Russian art, from the figurative mode of depiction originating in folk art to full-fledged abstract visions.

A separate section of the display has been dedicated to the model of Vladimir Tatlin’s “Monument to the Third International”, and various photographs taken of the three-dimensional plan that was never realized.

In addition to the diverse selection of paintings, the exhibition also features a film section with about a dozen screens: the short clips tell a variety of stories, ranging from official representations of the Russian Empire, the lives of Russian workers and soldiers fighting on the front lines (sometimes through imitated scenes), industrial production, and the destruction of churches, which resulted in the loss of countless invaluable art objects. The videos not only serve as interesting documents of the era, but also provide proof of an experimental period, the emergence of the language of film.

Some of the iconic artworks displayed at the National Gallery include Kitchen (1915) by Nadezhda Udaltsova, Suprematism (1915) by Kazimir Malevich, and Abstract Composition (1919) by Alexander Rodchenko.

“A Revolution in Art - Russian Avant-Garde in the 1910s and 1920s” showcases in detail the most important movements of Russian art in the first two decades of the 20th century, so even if you only know a little about this genre, you won’t regret visiting Buda Castle to view this colorful and inspiring collection.