Vilmos Zsigmond was born in 1930 in the regional city of Szeged. At the age of 17 he was sick and had to lie in bed for about three months. It was during this time that he read the book Artistic photography by Jenő Dulovits, which influenced him so much, that soon he grabbed a camera and snapped his was through the Hungarian countryside. It is interesting to note the visual and conceptual similarities between the members of the photographer's generation between the two World Wars. In the works of famous foreign photographers, we might immediately see hints of the sensitive, highly graphic pictures of André Kertész.

After he took photos of the Hungarian revolution, he fled abroad in 1956 – taking some 3000 meters of pictures. His photos were reproduces around the world in the press, but this was not enough to make him famous. In fact, after he arrived in America, he made it big with hard work and using his expertise in European cinematic language.

His persistence and talent resulted in him winning an Oscar Award in 1978 for his cinematography work in the film Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Fortunately, this coincided with the rejuvenation of the American film industry, which was well suited to his unique perspective and working methods, which took the director’s ideas into account. Vilmos Zsigmond worked exclusively analog technology, lab work and light-play.

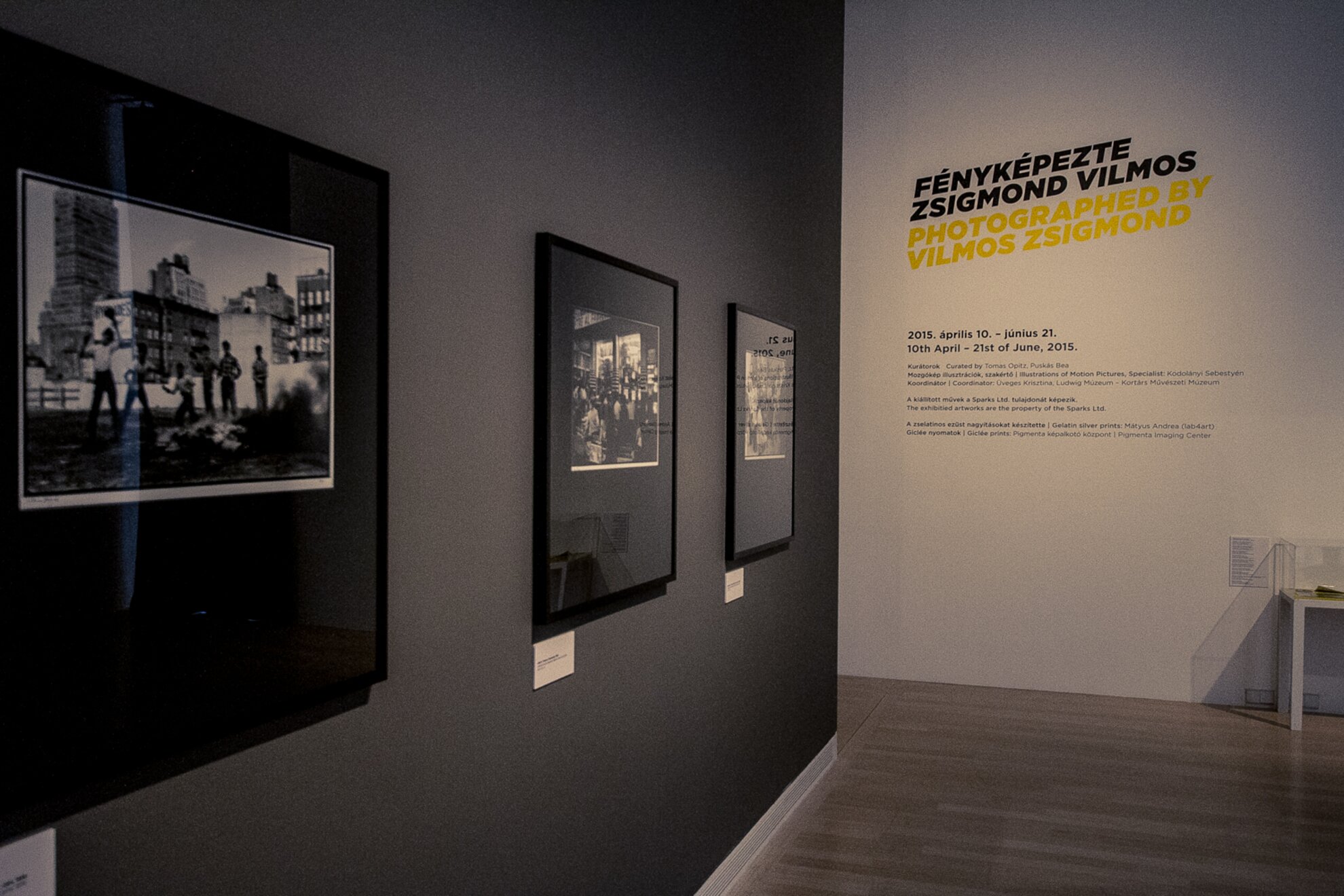

The material exhibited in the huge middle room at the Ludwig Museum builds upon the films’ chronology, work photos and film details. With this solution, even if only schematically, we can overview the artist’s cinematography career, from the black and white thesis film shot in the 50s in Hungary through to the colourful American western to science fiction and war dramas.

Vilmos Zsigmond’s talent did not know any genre or spatial bounds.

The most interesting part of the exhibition is the material that familiarises us with the photos of Vilmos Zsigmond, as well as the man himself. The first room’s material mainly shows the already mentioned Hungarian countryside, but the construction of a housing estate also appears among the photos, with a desolate area and a brick hut in the foreground. The latter image has the caption “Long live the proletarian internationalism.” The photograph showing Prague in 1955 is interesting as well, as there are no signs of the swarm of tourists that now converge on the city.

The next room’s pictures were taken during the adventurous, stormy voyage to America, as well as just after arriving, showing the streets, squares and parks of New York.

After the initial period, Zsigmond moved to California, where he started gain success. In this room, we can find numerous outstanding exposures portraying the streets of San Francisco, a baseball stadium and its parking lot, the night-lights of Los Angeles, and cultic rural locations such as Route 66 and New Mexico.

Finally, we can see some film instalments of the artist in a small room; and we can even take a peek at the Oscar statue.

The images taken on negative paper were enlarged after a long selection, exclusively for this exhibition.

Most of the master’s pictures are great works by themselves, but some photos are not only interesting because of their aesthetic quality but also because of their documentary value. Through them, we can learn about the scenes of the artist’s everyday life, the filming locations, the contemporary Hungarian countryside, major US cities and various distant landscapes. As the master said at the opening of the exhibition, during the weeks of images selection, he rediscovered many things thanks to the intentionally diary-like format of the photographs. While his wife writes a diary, he turns to his pictures. All the while, we can discover the world of Vilmos Zsigmond through the 150 exhibited pictures.