Marcus Goldson inherited a love of travel from his British parents – in the 1950s, his father worked in Trinidad and Tobago for the UK’s Colonial Service before heading to the Solomon Islands for his next assignment, but first he stopped in Kenya to visit an old friend from university. Enchanted by the African savannah, he abandoned his plans in the South Pacific and settled down with his Liverpudlian wife in Kenya, working for the nascent national government after the country gained independence; thus Marcus was born there and reared amid a lively setting of pristine nature, where a herd of zebras on the street was as commonplace as a traffic jam in London.

After spending his boyhood playing with Kenyan friends amid the countryside’s wild grasslands, Marcus was about 13 years old when his parents divorced and he went to live with his mother in Wales. Although Britain was the home of his ancestral roots, Marcus vividly recalls an overwhelming sensation of culture shock after leaving his African upbringing behind. “Music was certainly different – it was new to see ‘tribes’ of people dressing to the style of music they followed, like punk, 2 tone, and new romantic,” he recalls. “In Kenya we listened to Congolese or Swahili pop, Benga beat, and a lot of Abba!”

Partially inspired by the boisterous life and alluring works of Modigliani, Marcus first pursued a career in art by studying sculpture in England, but at age 23 fate pointed him toward Budapest while he worked in a London bar; there he met a colleague named Ildikó – born in Serbia to a family of Hungarian descent – who would one day become his wife. When she moved to Budapest for a new job, Marcus chased her to Hungary’s capital in 1993, “because she was exciting, and I wasn’t doing much else!”

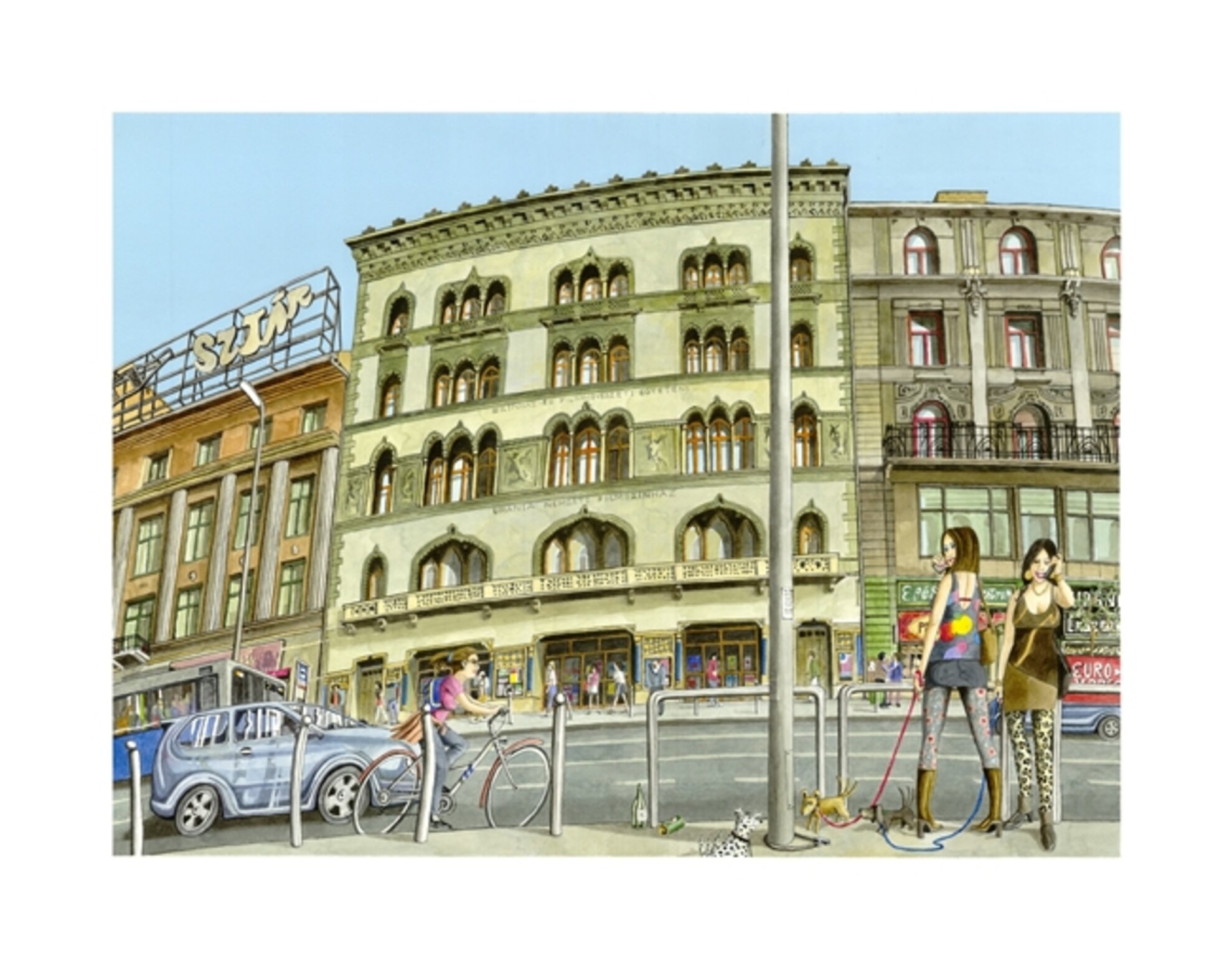

Again immersed in a totally unfamiliar culture, it took time for Marcus to appreciate Budapest’s idiosyncratic spirit, with its society still in a state of transition from the country’s recently concluded communist era. At around this time Marcus began experimenting with watercolors, bringing his paint set along with him around the city and on extended travels with Ildikó across Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and beyond. Although Marcus never pursued a single artistic style, over time he developed something of an exaggerated photorealism method to capture specific scenery that would suddenly inspire him, often planting himself amid a bustling street scene to capture its essence on the spot in cities like Cairo and Damascus.

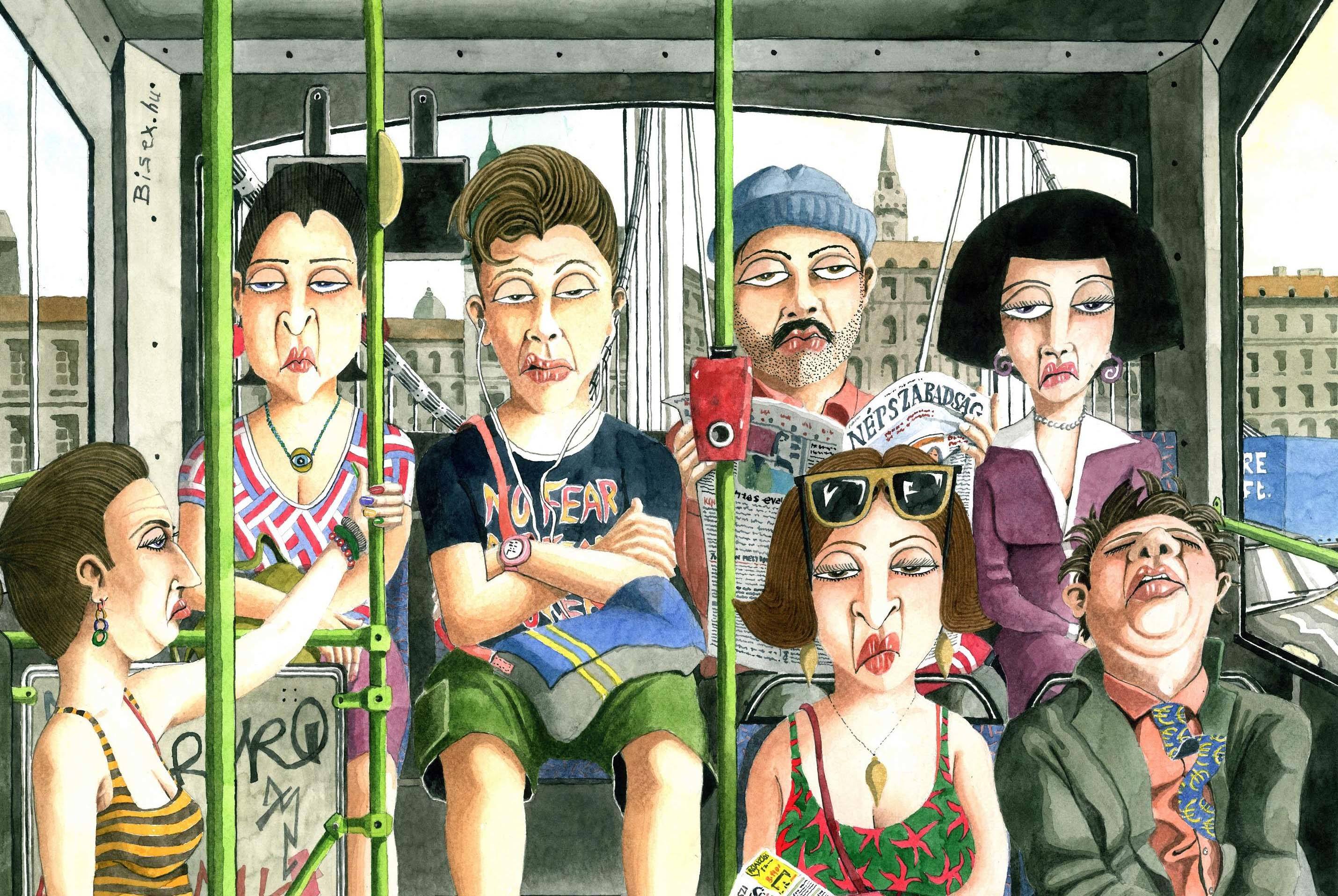

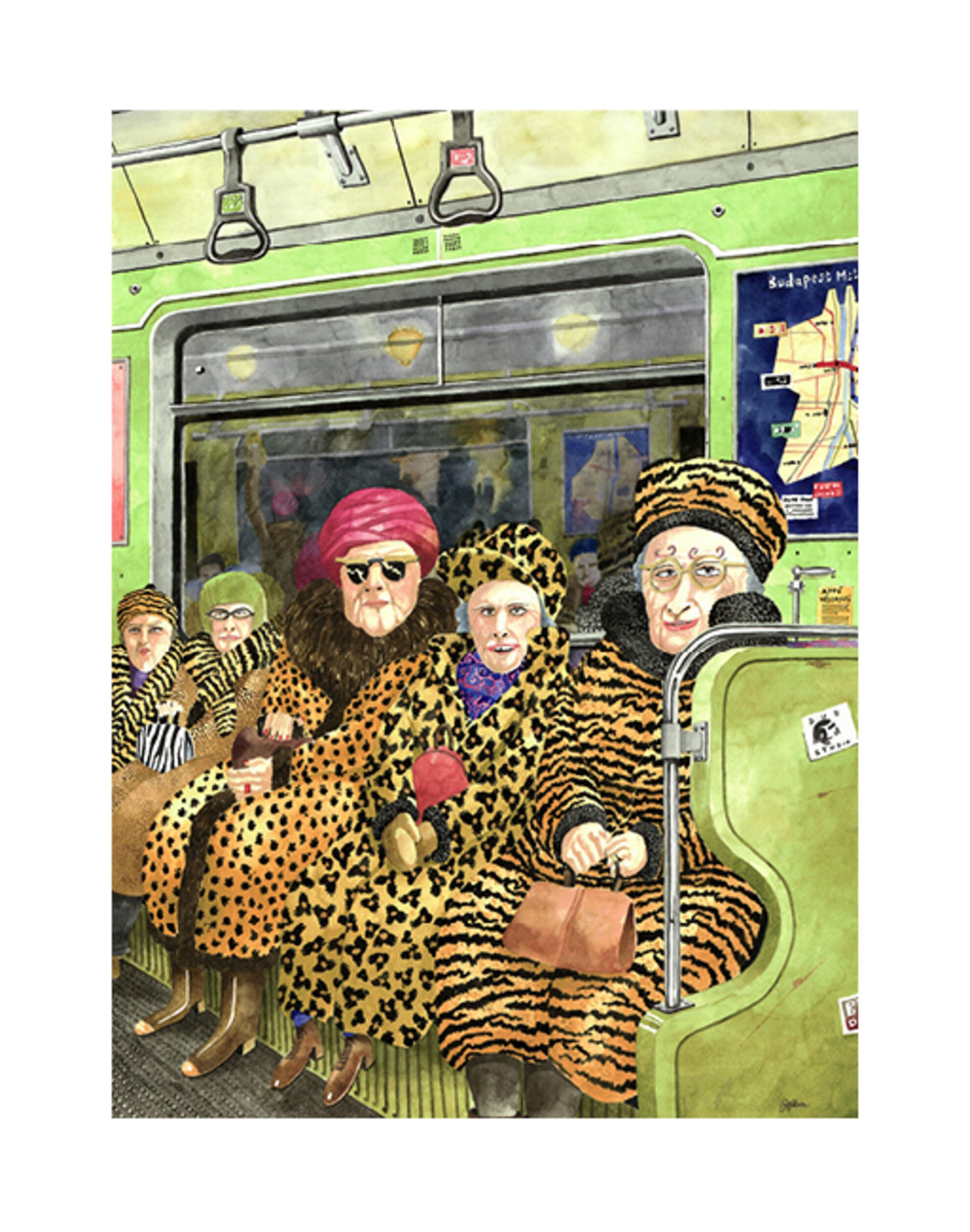

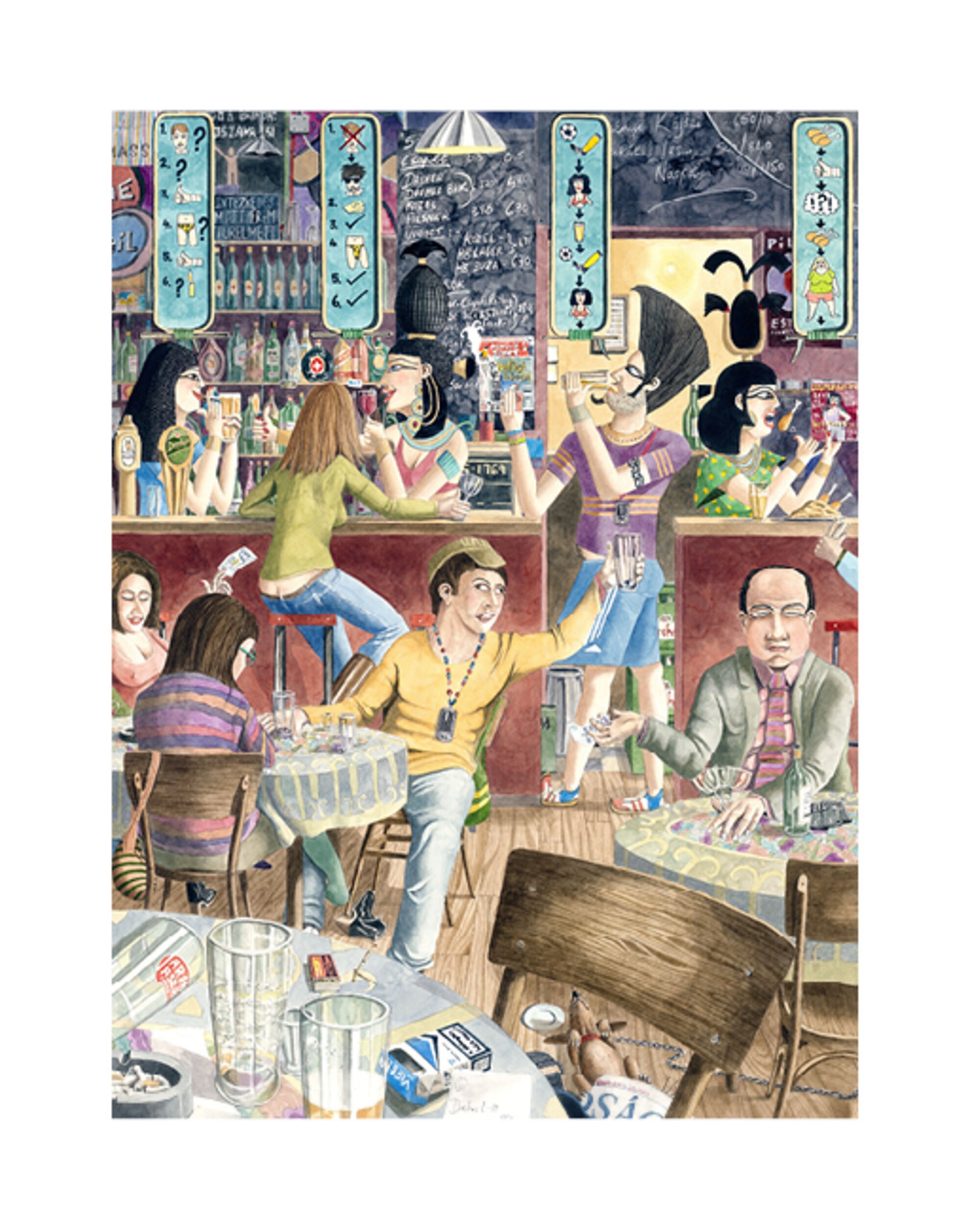

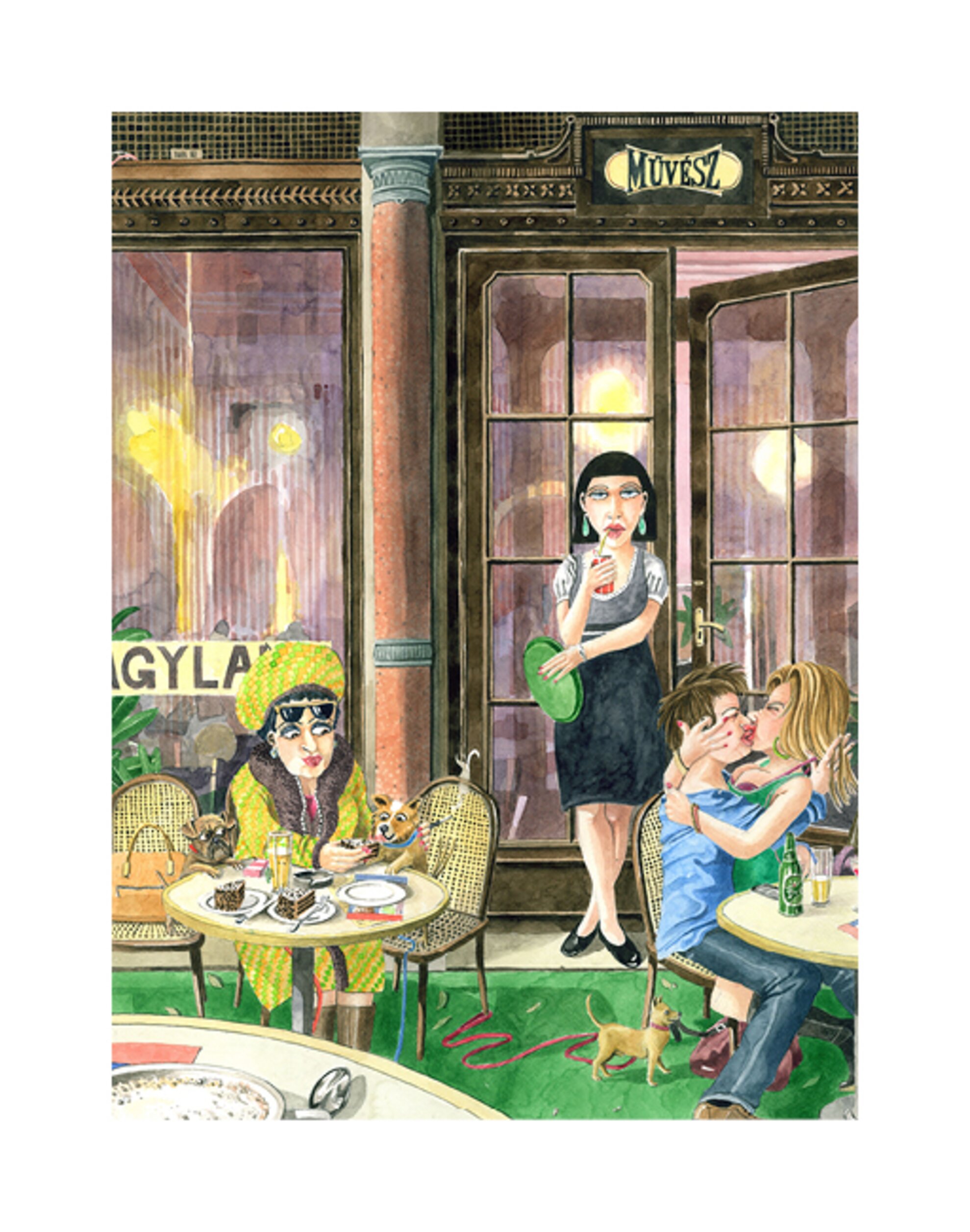

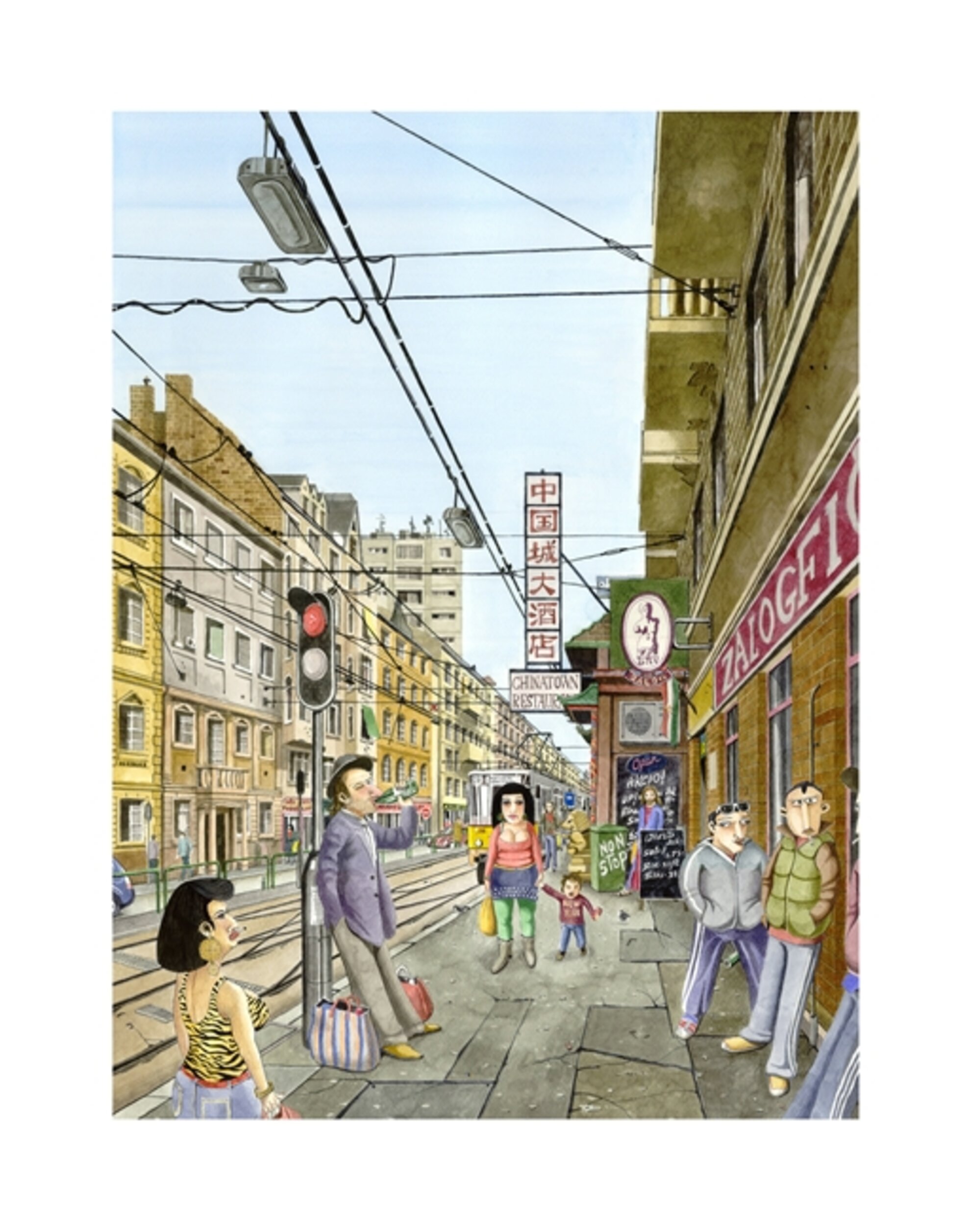

Back in his newly adopted hometown of Budapest, Marcus further augmented his style with a goal of illustrating the narrative of the scenes he painted, inspired by partying locals laughing amid a late night out, or old men drowning sorrows solo with drinks and cigarettes, or a young woman cycling with a smile amid chaotic traffic. Marcus found that these “models” amid the colorfully detailed backdrop of Budapest’s street scenes and landmarks – as well as its seedy no-name bars and less-than-prestigious neighborhoods – provided ample material to fuel his slightly skewed perspective, although it took awhile for this semi-documentarian approach to solidify.

“I spent a long time basically trying to figure out what I could paint – literally years! I wandered around Budapest a lot, and toward the end of the ’90s simply started drawing characters and characteristics that were classic Hungarian – guys drinking shots from the small bottles, moustaches that were still in fashion, etcetera,” Marcus explains. “It wasn’t an epiphany, but happened gradually.”

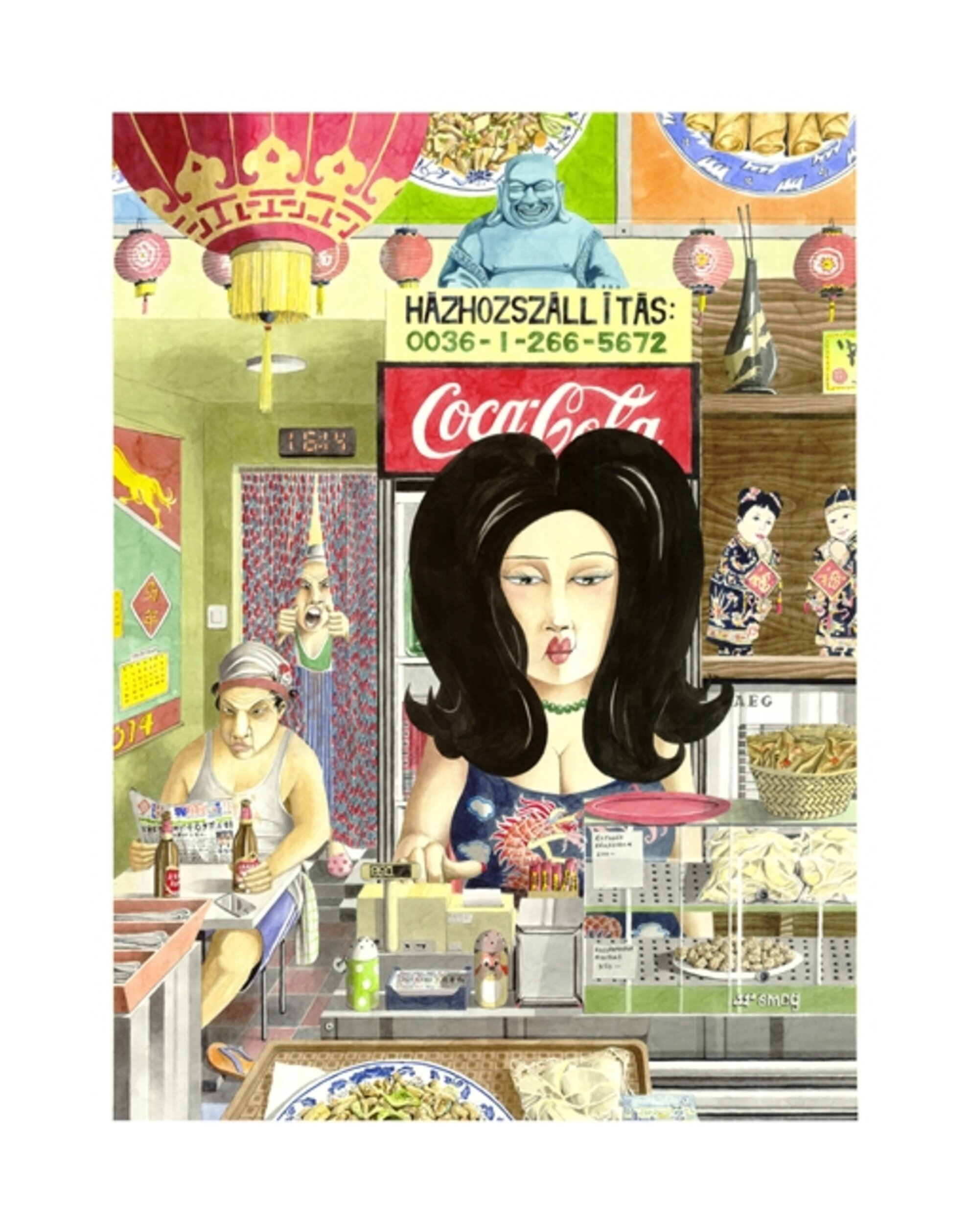

The expressive style that Marcus developed perhaps adds more emphasis to some of the outstanding features of his subjects, enhanced with actual colors of their settings – be they neon-lit night scenes or shop-lined streets in broad daylight – and almost all of his pictures are animated by people who look vaguely familiar to anyone who spends a little time in Budapest, supplemented with local logos for Hungarian products like Borsodi beer and the Népszabadság newspaper. Many of the characters that Marcus depicts are based directly on individuals that he observes, or can be a composite of several different people, yet more fanciful figures (like a smoking dog or an Ancient Egyptian bar staff) also appear in his works.

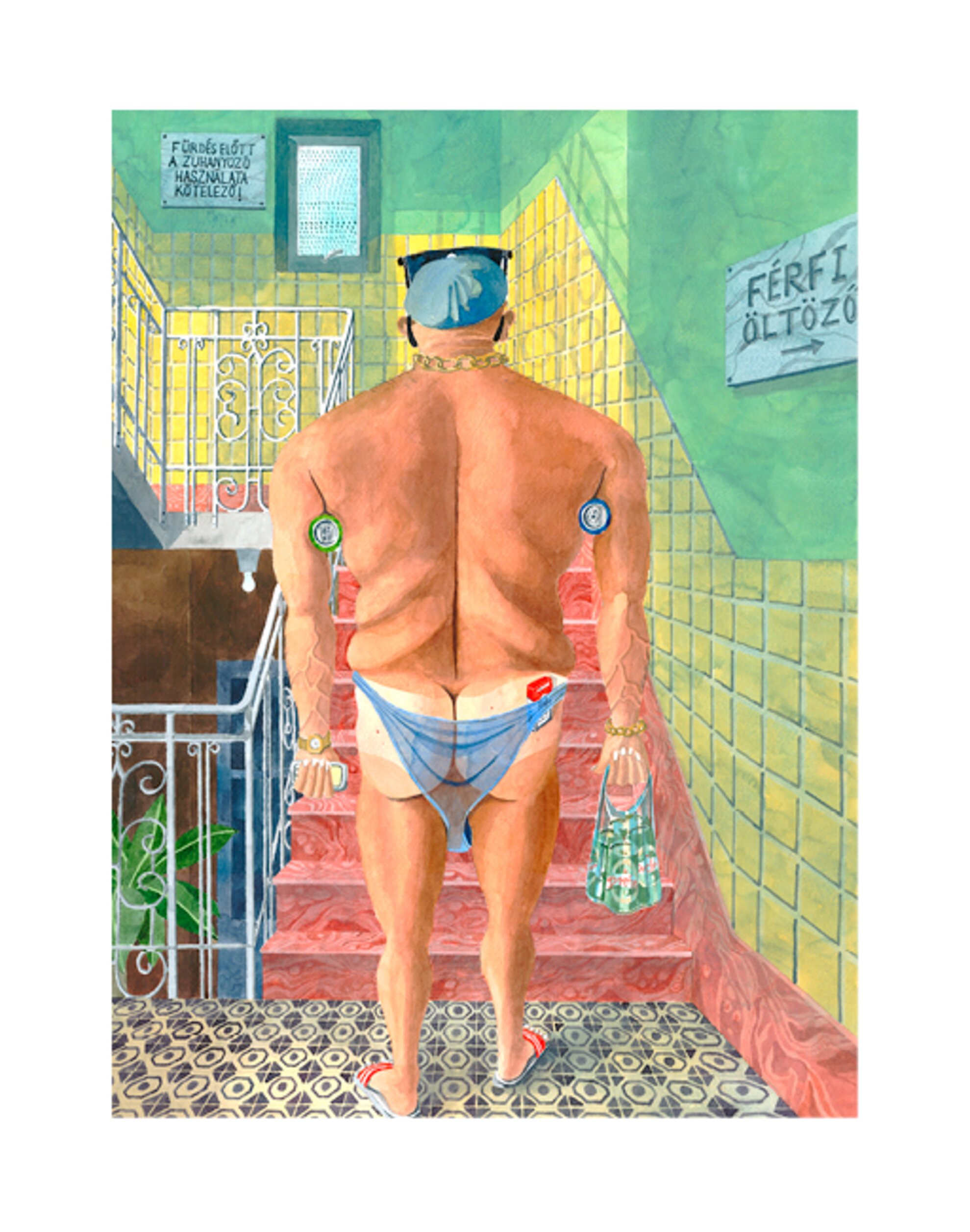

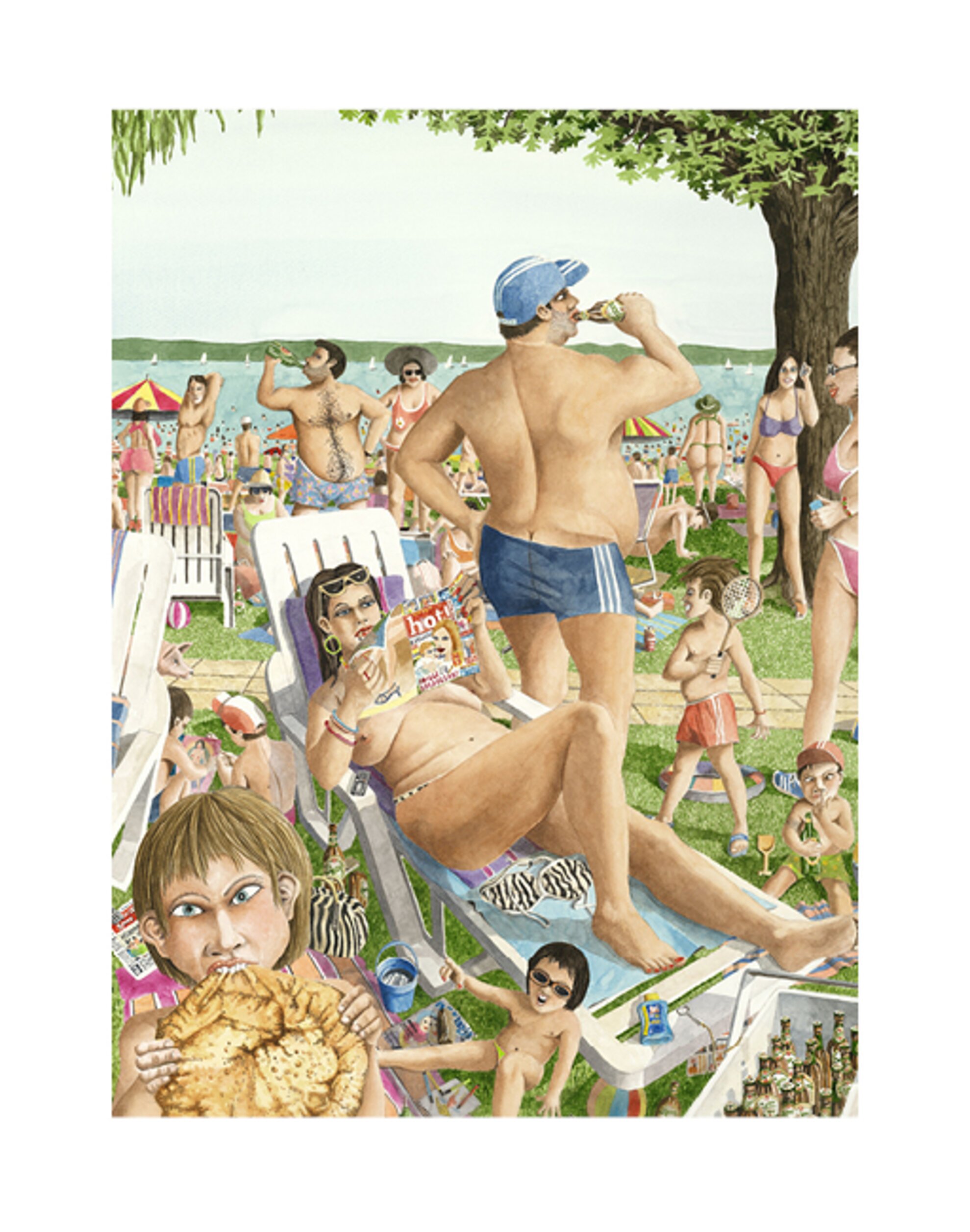

Marcus tends to exaggerate the grotesque aspects of his subjects to comic effect, be it a drunkard’s overhanging gut or a bureaucrat’s protruding nipples, and while such details may strike some viewers as unpleasant portrayals of Budapest’s diverse denizens, the artist is proud of the fact that his works can elicit such a powerful response. “If viewers hate it, that’s almost as good as them loving it, because at least they’re reacting,” he says. “I think apathy is the worst possible reaction to a picture.”

Fortunately, many Hungarians and foreigners alike find Marcus’s works appealing enough for widespread purchase – in addition to numerous private buyers of the originals (Félix Hélix is something of a miniature museum for quite a few of his pieces), the artist is frequently commissioned to draw or paint for publications including Budapest Week, Cosmopolitan, Playboy, Forbes, and the now-defunct Time Out Budapest; for the latter magazine he had a picture in almost every issue, including two covers.

As Budapest’s saga continually progresses over the years following his arrival, Marcus is finding that many formerly iconic hallmarks of city life here are now disappearing – such as smoking inside of pubs (now illegal, but once ubiquitous) and an influx of vacationers replacing locals around downtown Pest as Hungary’s tourism industry grows – and these changes are faithfully reflected when viewing Marcus’s pictures over the years. In this way, his works provide a colorful chronicle of Budapest culture as it changes over the years, frequently sparking memories in the minds of both locals and longtime expats.

In recent years, as Marcus and Ildikó started a family with daughters Jazmin and Anika, the artist’s subject material started to include more family-friendly Hungarian settings such as the crowded shores of Lake Balaton during summertime… while still featuring plenty of the beers and butt cracks omnipresent in such settings. However, Marcus now finds himself nostalgic for the natural beauty of his native Kenya, creating complex paintings incorporating interweaving scenery from his memories of Africa, including curling elephant trunks, towering palm trees, zebras running from heavy rain, and other images of the wide-open savannah.

A few weeks ago, Marcus premiered a special series of Risograph prints highlighting these African-based images: “The Wild Collection”, published at the Brody Art Yard (where they are available for sale). Marcus plans to bring his family to visit Kenya again in the near future, but although Budapest culture can still shock him from time to time, he definitely feels at home here now after two decades and an unpredictable artistic journey. “If I could have seen into the future 20 years ago, I would have been a little perplexed as to the kind of art I was producing,” he says, “but no less proud of it.”

Check out Marcus Goldson’s official website for more information and to see samples from his entire oeuvre.