The courageous Hungarian freedom fighters, fed up with a regime that reduced the Magyars to pawns in a global game of neo-colonialism, openly defied the heavy-handed authority of nuclear-armed Russia. And while the movement was eventually quashed by the overwhelming firepower of the Red Army, the Hungarian people proved that their national identity would not be compromised for the sake of the Cold War – their brave resistance tore the first rip in the Iron Curtain, and now almost six decades later, symbols and scars from the 1956 Revolution are still visible across Budapest and far beyond.

Back in the late 1940s, soon after the Soviet army defeated Nazi-controlled Hungary at the close of World War II, the Kremlin-backed Hungarian Working People’s Party (HWP) became the country’s sole governing body, and steadily drove the nation toward economic collapse, with its focus not on the welfare of the beleaguered Magyars but to support Joseph Stalin’s brutal rule over the Eastern Bloc states. After Stalin’s death in 1953, power struggles broke out in Moscow that eventually led to the rise of Nikita Khrushchev as the new Communist Party chief; amid the political wrangling, mass demonstrations against Soviet domination broke out in East Berlin, which were quickly and violently quelled. Sensing widespread unrest amongst the satellite countries, Khrushchev made a “secret speech” to the USSR’s Communist Party in February of 1956, in which he revealed and denounced the atrocities committed by Stalin, and expressed desire for reform. However, as the content of this speech soon leaked westward, many USSR-controlled nations became disillusioned with Soviet-imposed communism.

In the summer of 1956, workers in Poland demonstrated for improved living conditions; armed Russian forces broke up these protests with merciless ferocity, slaughtering nearly 100 activists in the clash. Hungarian intellectuals observed this event with grave alarm, as Magyar life standards were also plummeting. Angered by their own government’s complicity with Soviet domination, Hungarian students nationwide began organizing illegal independent groups in mid-October with the goal of supporting their Polish counterparts and establishing new democratic rights.

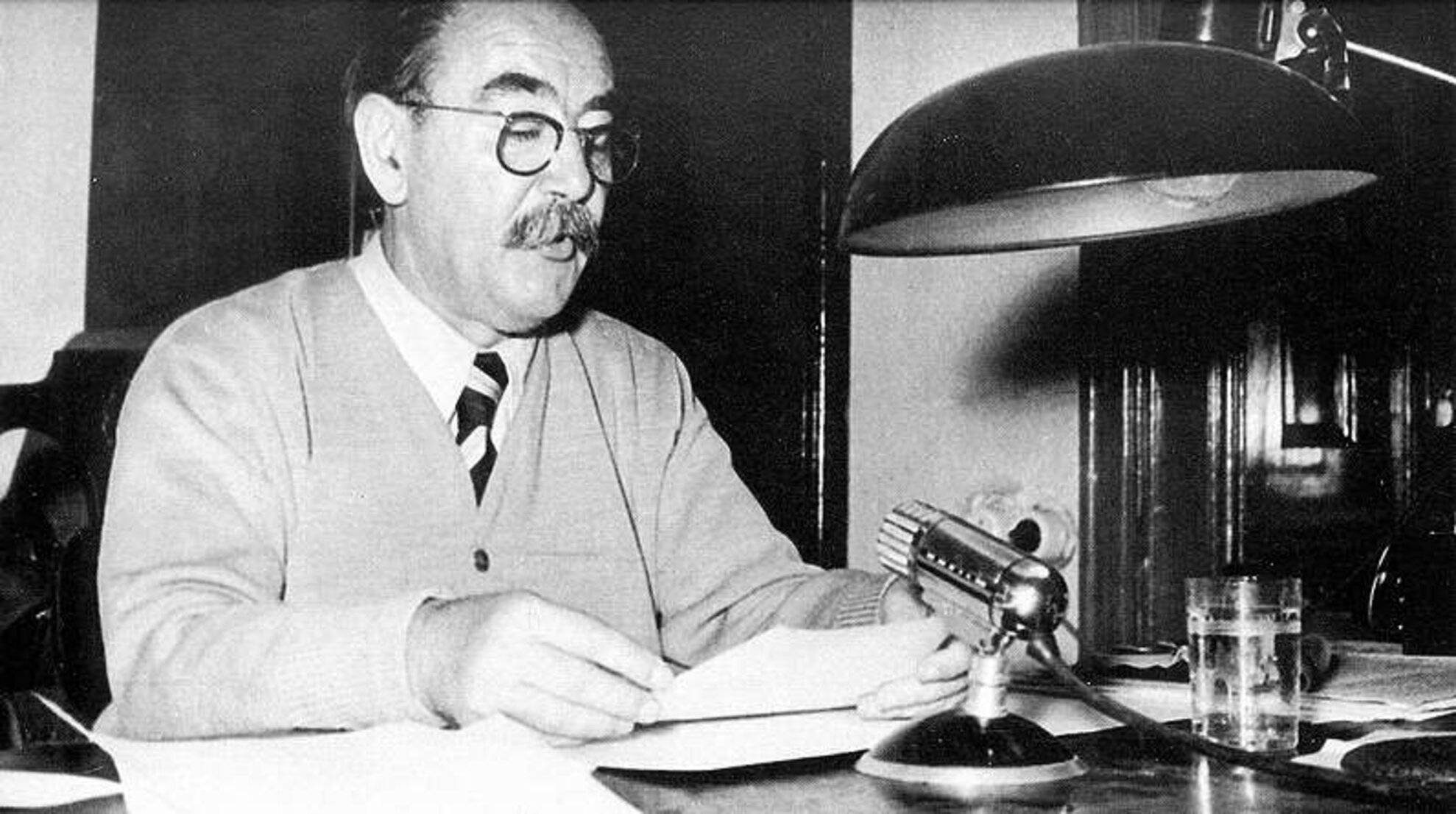

On October 23rd, simultaneous peaceful demonstrations were launched across Hungary and in the capital, where the students were soon joined by thousands of civilians, marching together through the streets of Buda and Pest to join forces at Bem Square (named for József Bem, a Polish general who was a leader of Hungary’s 1848 Revolution). As a proclamation of demands was read to the restless crowds, a contingency of students went to the Magyar Rádió building on Bródy Sándor Street, where they insisted on broadcasting their demands. Meanwhile, the brunt of protestors left Bem Square to gather in front of the Parliament House at Kossuth Square, where they demanded to hear from former Prime Minister Imre Nagy, a popular reformist who had been ousted from power by the HWP a year earlier. Nagy eventually appeared, delivering an underwhelming speech that failed to calm the unrest – especially as he began his address with the customary Soviet-style greeting, “Comrades…”

By this time, armed members of Hungary’s communist secret police – the dreaded State Security Office (ÁVH), whose headquarters were in the building that is now the House of Terror Museum – gathered at the Magyar Rádió demonstration, and when a bullet was fired at the protestors from one of the windows, a volley of shots ensued; the activists were soon equipped with small arms provided by sympathizing soldiers and police. In the escalating chaos that followed, the demonstrators managed to take control of the radio building, and a massive Stalin statue by City Park was toppled and dragged to Blaha Square, where it was smashed to pieces by the demonstrators-turned-revolutionaries. Meanwhile, Magyars took down Hungarian flags – blighted at the time with Soviet insignia in the center – and cut out the unwanted foreign emblems before raising the national symbol again with the hole proudly in the middle; today, this is the defining symbol of the 1956 Revolution.The next morning, as Budapest residents defied a curfew to erect blockades and stockpile arms in anticipation of the arriving Soviet military, word spread that similar demonstrations had also turned violent across the nation. With increased resolve, the resisters established garrisons at strategic points around Budapest to confront approaching Russian tanks. The HWP leadership hadn’t expected the revolutionaries to resist in the face of such war machinery, but using urban-guerilla tactics, the rebels repelled several Red Army platoons along major city thoroughfares. Reinforced bases were located at Boráros Square by the Danube, Baross Square by Keleti Station, and within the Corvin Passage, which would become the fiercest stronghold of the 1956 Revolution.In the days that followed, frequent attacks and skirmishes took place across Budapest and the countryside, as village-based freedom fighters strove to hinder Soviet brigades heading toward the capital. Workers nationwide launched strikes in solidarity with the resisters, and more public demonstrations continued demanding radical change in government. In one particularly gruesome incident, ÁVHtroops opened fire on a nonviolent crowd of approximately 10,000 demonstrators gathered before the Parliament House on October 25th, a massacre that killed around 100 people and injured hundreds more; bullet holes from that tragedy are preserved to this day on buildings surrounding Kossuth Square.Appalled by such actions, the alienated Hungarian police and military sided with the revolutionaries, leaving the HWP with only the Soviet army and the ÁVH for armed support; both groups only further antagonized the Magyar rebels. With time, the freedom fighters grew even stronger, controlling increasingly more territory throughout Pest’s Districts VIII and IX, and setting up new garrisons in Buda at Széna Square and in the Castle District. Resistance mounted in villages and cities nationwide, with several local governments ceding control entirely to the independence movement. By October 27th, the HWP finally conceded that this was not a movement of radical troublemakers, but a true revolution, and in order for the party to maintain any semblance of power, they would need to address the protestors’ demands that even Soviet military might could not dissuade.

On October 28th, Imre Nagy was restored to power, and while struggling to establish order, he announced that a new government would be formed that would address the activists’ ultimatums, including disbanding the ÁVH and negotiating a withdrawal of Soviet troops. In the next few days, with the Hungarian people united, Nagy did his best to consolidate power and legitimize the revolutionary actions, declaring an end to the one-party system and bringing together various factional leaders to work out a renewed government structure.

However, back in the Kremlin, Khrushchev decided that Hungary’s breaking away from the Soviet Union was unacceptable, and after determining that Western powers wouldn’t interfere, he ordered a major military strike to bring the rebelling Magyars back into line. In early November, Nagy received news of the approaching Red Army, and in a desperate move he declared that Hungary was withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact, hoping that this would encourage the United Nations and Western forces to come aid the fledgling Magyar democracy.

Alas, this hope was to no avail – on the morning of October 4th, the Soviets launched another assault with their newest and most powerful tanks and warplanes, against which the ragged revolutionary forces didn’t stand a chance. Nonetheless, many holdouts valiantly continued the resistance for days on end, desperately defending the hard-fought victories they had briefly attained. After making repeated (unanswered) calls for Western support, Nagy took refuge in the Yugoslav embassy by Heroes’ Square, where he and his closest allies stayed for nearly a month before they were assured safety if they left – only to be abducted immediately and taken in captivity to Romania. Later, back in Budapest, Nagywas given a show trial and immediate execution; today a memorial statue of Nagy stands atop a symbolic bridge overlooking Hungary’s Parliament House.When the dust settled and the 1956 Revolution was officially vanquished, Budapest was in shambles again, only 11 years after the city’s total devastation during WWII. More than 2,500 freedom fighters and civilians died, over 20,000 were wounded, and some 200,000 fled the country as refugees. The new Soviet-imposed government arrested about 5,000 revolutionaries; many were sentenced to life imprisonment, and 229 of them to death. To this day, the damage inflicted by street battles of 1956 still pockmark varied structures all across Budapest.Still, the 1956 Revolution made a major impact worldwide – communist sympathizers turned away from the movement after seeing the carnage that the Soviets had wrought here, and Russia’s prestige as a superpower was tarnished permanently, until the USSR collapsed in 1991. By that point, Hungary had finally achieved the independence that it now enjoys, for the first time in almost half a millennium – at long last, the dream of so many revolutionary movements in Magyar history is now a reality, and the fate of this country will be determined by independent decisions of the Hungarian people.