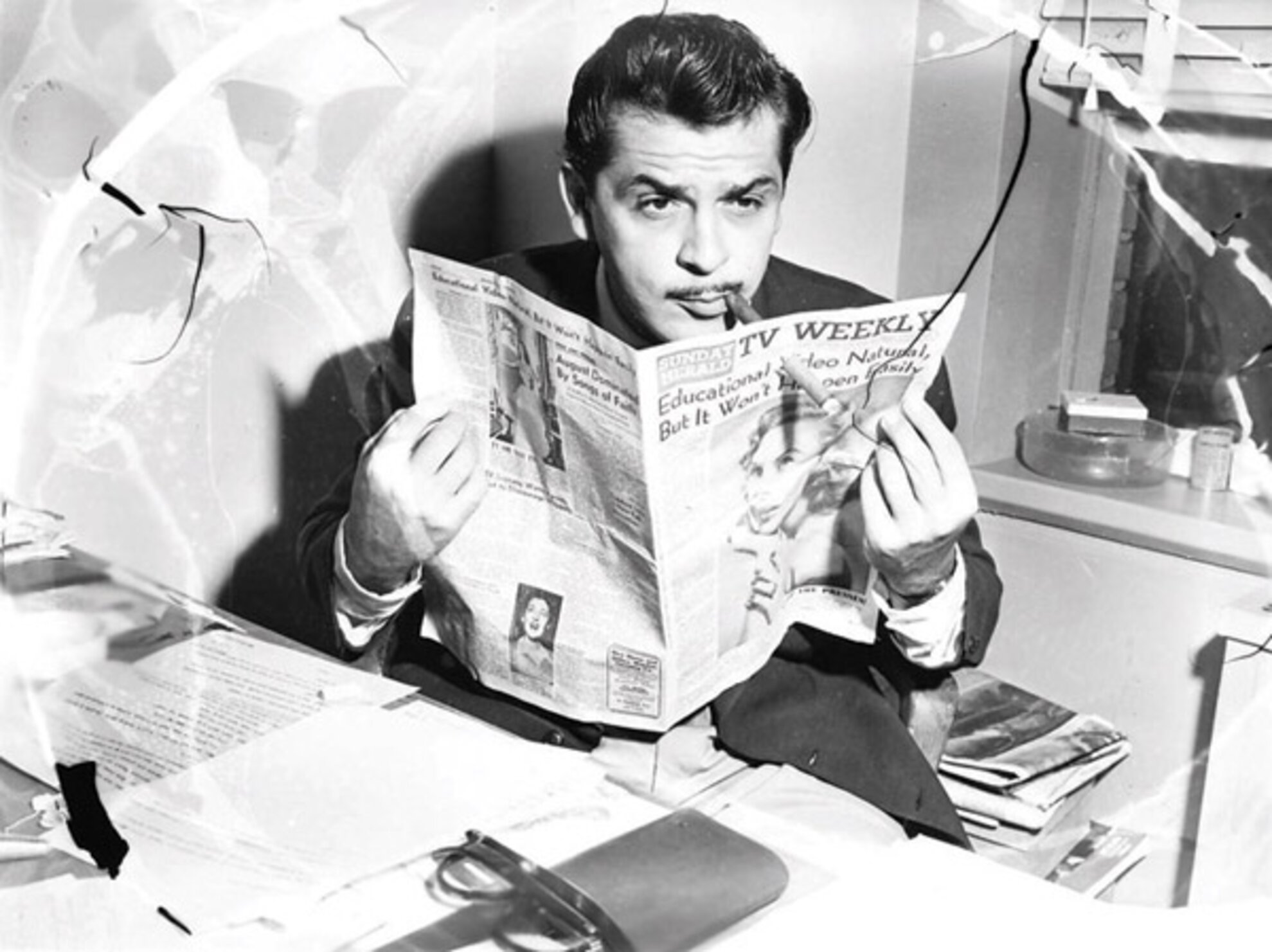

On a rainy night in Beverly Hills in January 1962, comedian Ernie Kovacs left a Hollywood party full of celebrities to drive home. Giving his wife, Edie Adams, the keys to his latest luxury car so that she could join him later, Kovacs took her Chevrolet Corvair station wagon. Skidding on the wet road, he lost control of the vehicle, crashing into a telegraph pole. In his hand was his trademark cigar, flung from the car unlit, his arm outstretched towards it, a haunting image captured by the photographer who was first to arrive on the scene.

At his funeral, attended by Groucho Marx, Edward G Robinson and Buster Keaton, as well as his pallbearers Frank Sinatra, Jack Lemmon and Dean Martin, the pastor read a eulogy in Kovacs’ own words: “I was born in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1919, to a Hungarian couple. I’ve been smoking cigars ever since”.

Nothing in moderation

On his gravestone at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Hollywood Hills, where Edie Adams was to join him in 2008, reads the following: “Nothing in moderation – We all loved him”.

Josh Mills grew up in the house his mother, Edie, and her first husband, Ernie Kovacs, called home. “I remember the suits of armour, the duelling pistols, the polar bear rug,” Josh tells We Love Budapest via Zoom from California. “The wine cellar was Ernie’s mancave, with a medieval-looking latch and a ‘Not Now!’ sign hanging outside. The fake cobwebs… It really felt like I was in the Addams Family! Many of the items, were props for his TV show. I knew who he was.”

Today Josh works in music publishing. His whole life has been one long fascination with popular culture – no wonder, given that his mother never threw away any of her husband’s belongings. So precious did she consider his work that she even sold her own jewellery to purchase the rights to grainy tapes of their seminal Ernie Kovacs Show from the early 1950s, rather than have some unwitting employee record over them decades later.

“There are things everywhere,” says Josh. “Thousands of tapes, reels, videos, letters, papers… I figured it was no good sitting in my garage. If I didn’t do something with it, then it was just going to collect dust. People need to see this stuff and enjoy it for themselves.”

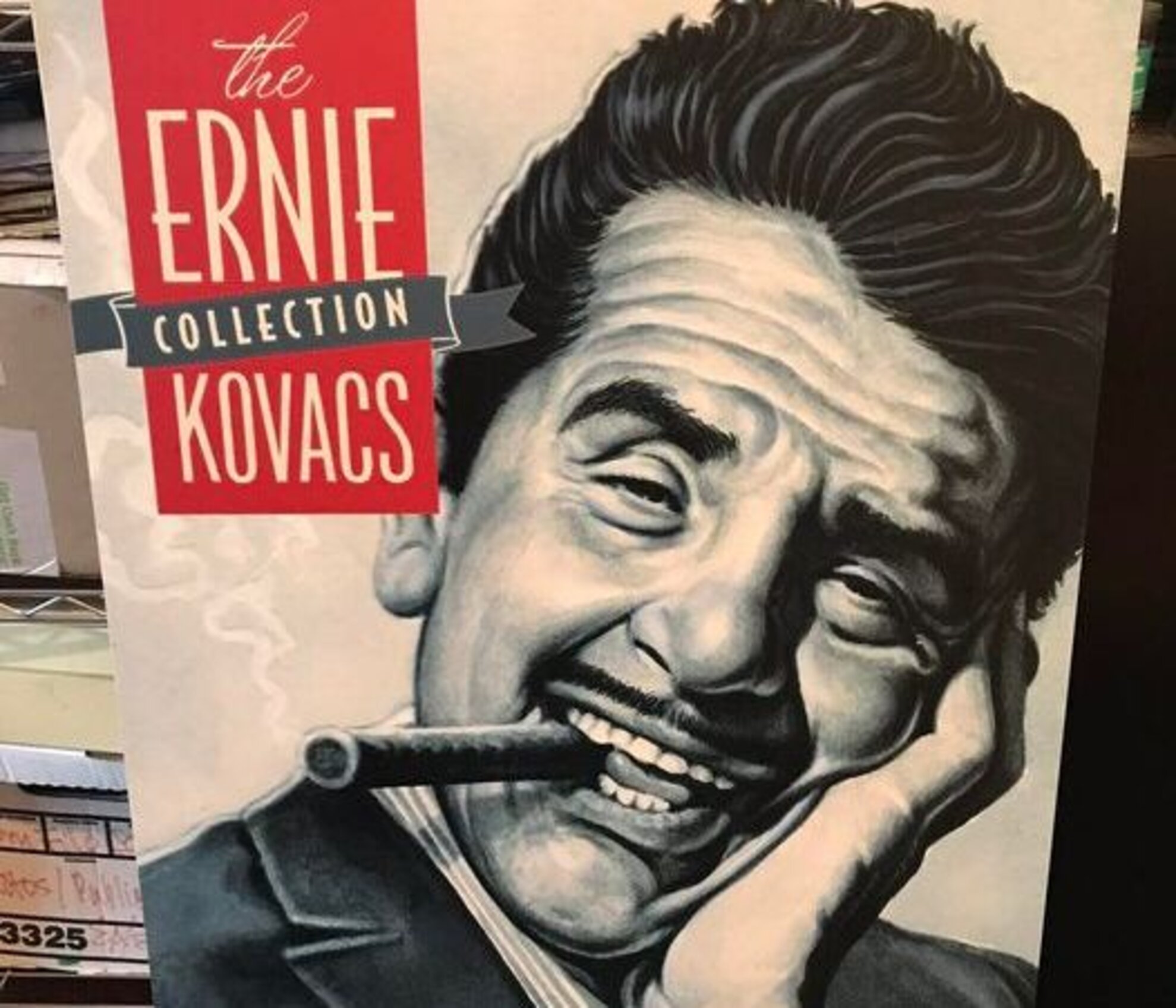

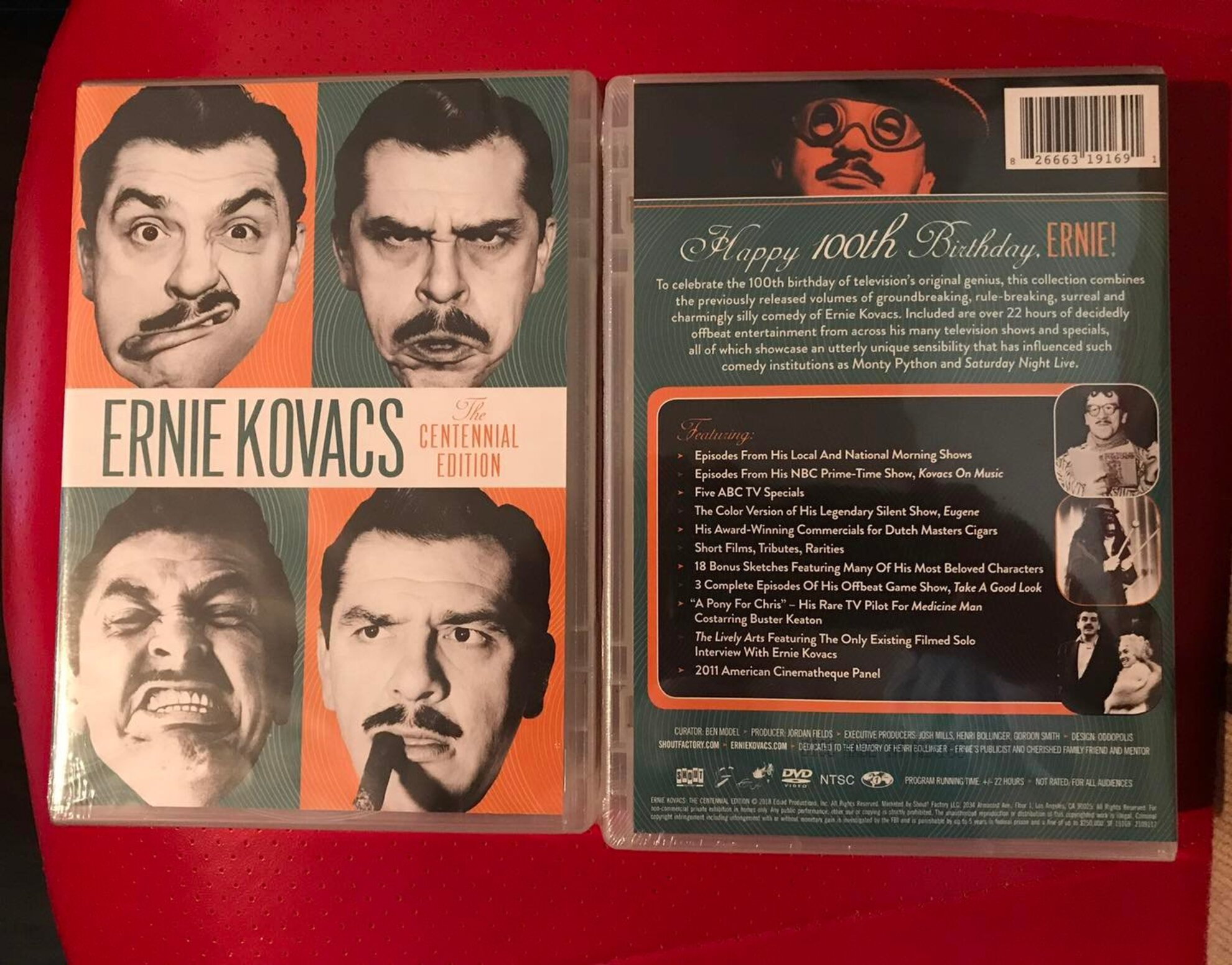

In 2011, a six-disc DVD compilation of the comedian’s work, The Ernie Kovacs Collection, more than 13 hours’ worth of footage, was released to rave reviews. In 2019, Josh began work on a coffee table book due for publication by the end of this year, the 60th anniversary of the car crash that killed the king of TV comedy. In 2020, Josh came to Hungary to give a talk on Kovacs, where he met Adrienn Dorsanszki, currently writing her master’s thesis on this television pioneer.

Naturally, Edie Adams had an emotional attachment to items belonging to her first husband and screen partner. Josh, her son by her second marriage, duly dedicates his mission to his mother, who did years of cigar commercials to raise her children and her stepdaughters. But there’s more to this scenario than happy memories and filial duty.

Adrienn Dorsanszki could have chosen any number of humorists, foreign or Hungarian, to analyse. She chose Kovacs. “He realised he could step inside people’s living rooms and open up the viewer to something else, to take them out of that little box,” she explains.

What is it about those early TV shows that makes Ernie Kovacs so special?

“His upbringing was in the theatre,” begins Josh. “But I think his main influence was his strange family. His mum was nuts. She bought him a pony, in the middle of Trenton, New Jersey. His Dad was a beat cop there during prohibition.”

Ernie’s father had emigrated from Tornaújfalu, today Turnianska Nová Ves in Slovakia, in 1906. Ernie was born in 1919. His parents then became awash with money during the bootlegging days of prohibition. The budding young performer moved from local theatre to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, although spent much of his time watching low-grade movies and listening to the radio.

In the early 1940s, he started working at a local station in Trenton, getting up to various antics on air. Much of what he did was unconventional but he got away with it and what’s more, he gained an audience.

The modern television set had not long been presented at the World’s Fair in New York, in 1939. No-one, least of all the newly expanding networks, quite knew what radio with pictures should look like. When NBC Philadelphia affiliate WPTZ was auditioning in January 1950, Ernie Kovacs showed up – dressed in a barrel and shorts in the depths of winter. He got the job. He had realised, instantly, that radio with pictures was exactly what television shouldn’t be.

In no time, he was on the first version of breakfast TV, chucking water at the weatherman. Goats, gorilla suits, anything to keep an audience entertained, Kovacs did it, on next to no budget, by dint of his own wit and spontaneity. He invented characters, drawn from real life then exaggerated for comic relief. He used primitive video effects, played pranks on the camera crew, anything and everyone was fair game. There were no rules so he just made up his own.

TV tomfoolery

“He was a very visual comedian,” says Josh. “He broke the mould and figured out how to use the medium of TV to its best advantage. He made it a spontaneous experience.”

And this was Truman’s America, when the McCarthy witch hunt was rooting out suspected Communists and weirdos no matter how innocent. Kovacs may have made a name for himself but that name is as Hungarian as pálinka.

“He was on the cusp of something completely different, completely unique,” says Adrienn, “while still touching reality”.

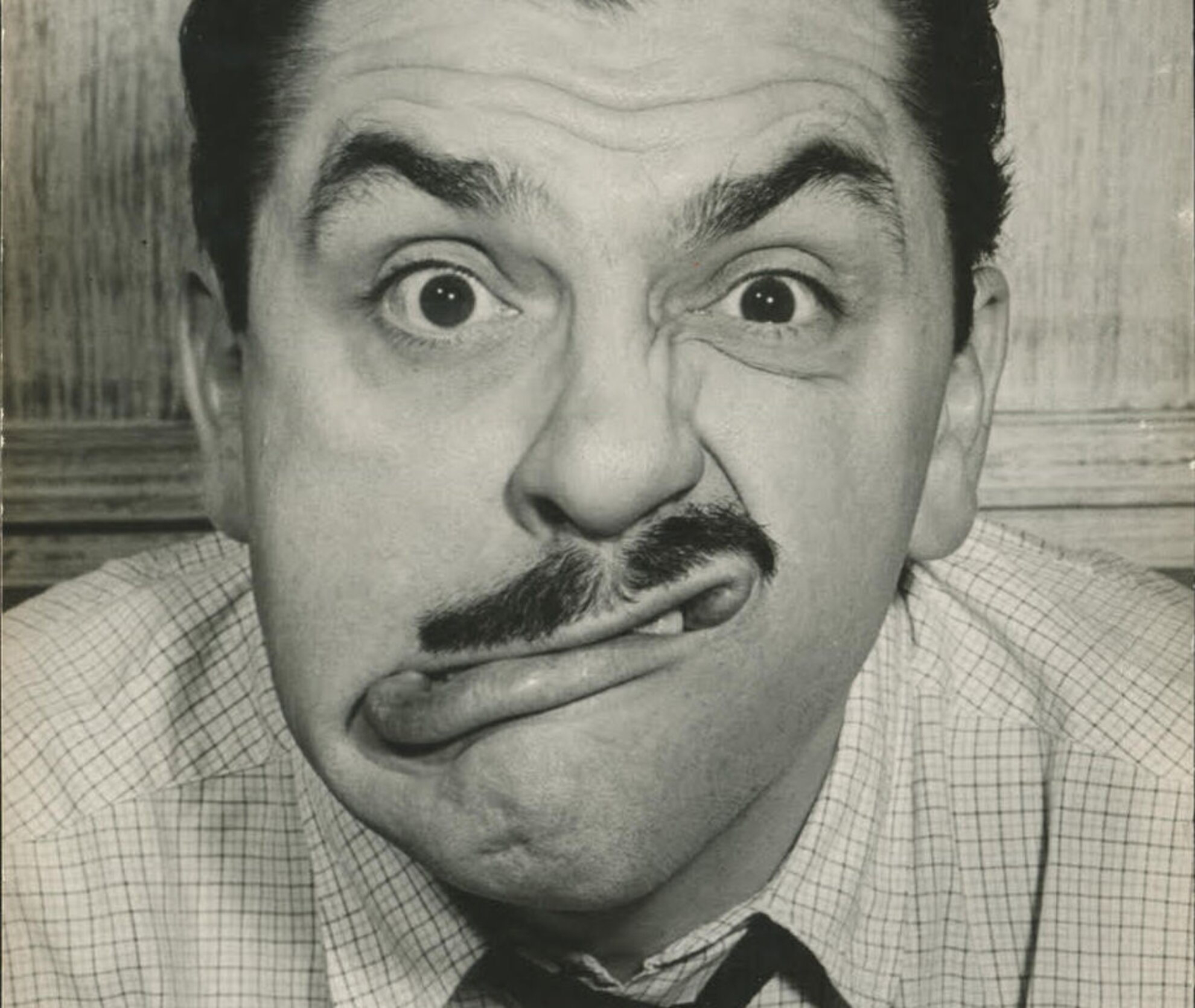

Grounding the anarchy were deadlines, time limits and an internal logic to his comedy. There was also Edie Adams. Then in her early twenties, this classically trained singer had been hired for a Kovacs show in 1951. “He was standing there with a hat, a moustache and a cigar,” she was to say later. “He looked like something out of a B-movie. Nobody in my family looked like that.”

Pretty soon, they were a couple. “He taught me how to enjoy life,” she said in a later interview. “Ernie listened to his inner child. If he wanted it, he bought it. The champagne, the cigars… nothing in moderation! ‘You only go through this thing once’, he once told me about his attitude to life. ‘This is not a rehearsal’”.

Few of their shows were rehearsed either. “When you strive for perfection, sometimes you miss a lot,” Edie Adams explained in the same interview.

While comic foil Edie provided the props and lined up the gags, the Margaret Dumont to his Marxian circus, Kovacs invented characters, some drawn from his colourful Hungarian heritage. There was drunken chef Miklós Molnár, probably the role model for his Swedish counterpart on The Muppet Show two decades later. There was the lisping, martini-sipping, ode-delivering aesthete Percy Dovetonsils.

And then there was Eugene, the bumbling surrealist and vehicle for what could be considered the comic’s greatest triumph: The Silent Show. Granted 30 minutes of prime time at the dawn of the colour TV era, Kovacs prepared the viewer with this opening line: “There’s a great deal of conversation that takes place on television. I thought you might to spend half an hour without any dialogue at all”.

“Ernie always set the parameters first,” explained Edie Adams years later. “Then he could do what he wanted.”

Hackers and humour

“This guy hacked the whole system,” says Adrienn Dorsanszki. “He understood the psychological process, the essence, of how humour works.”

When first outlining to studio executives his plan for 30 minutes of

complete silence in living rooms across America on a Saturday night, Kovacs unsurprisingly

failed to convince them. After all, this was everyone’s first time to shine in

colour on TV. Silence would not have been the first option on the whiteboard.

So,

leaving his coat and briefcase at the meeting, Kovacs walked out. And kept

walking. After several blocks, he formulated an idea for a novel. Within two

weeks, he had written it. He then went back, delivered The Silent Show as he

had conceived it, won a Sylvania Award, the Emmy of its day, then landed a movie

role.

By then, Kovacs was firmly established in Hollywood. Stars such as Jack Lemmon and Frank Sinatra would perform alongside him in monkey suits as that week’s Nairobi Trio, a spoof musical act whose anonymity was assured behind the ape masks picked up at the local joke store.

These same celebrities would be the ones to carry the comedian’s coffin

at his funeral in 1962. Edie Adams, unwittingly landed in huge debt through her

husband’s profligate lifestyle, refused the many offers of financial support

and rolled up her sleeves.

Las Vegas, cosmetics, cigar commercials, she worked every

day she could. That’s her in Stanley Kramer’s seminal comedy, It’s a Mad, Mad,

Mad, Mad World, made later in 1962 with an all-star cast who helped her smile again.

“Life is just more beautiful with humour,” as Adrienn puts it.

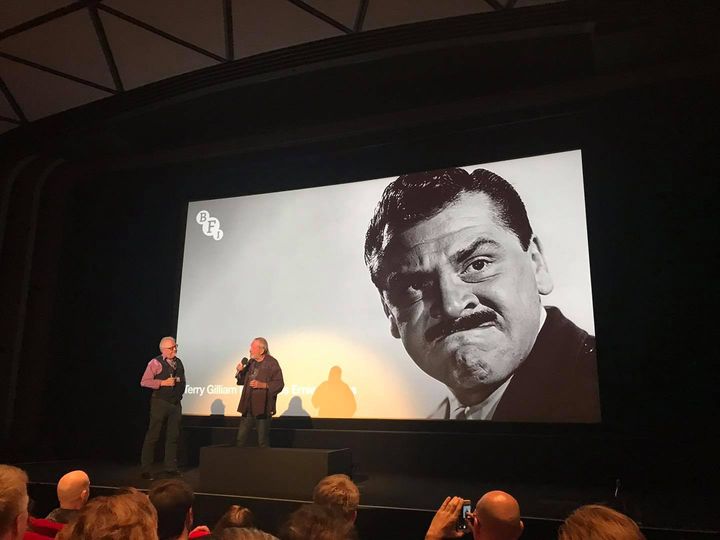

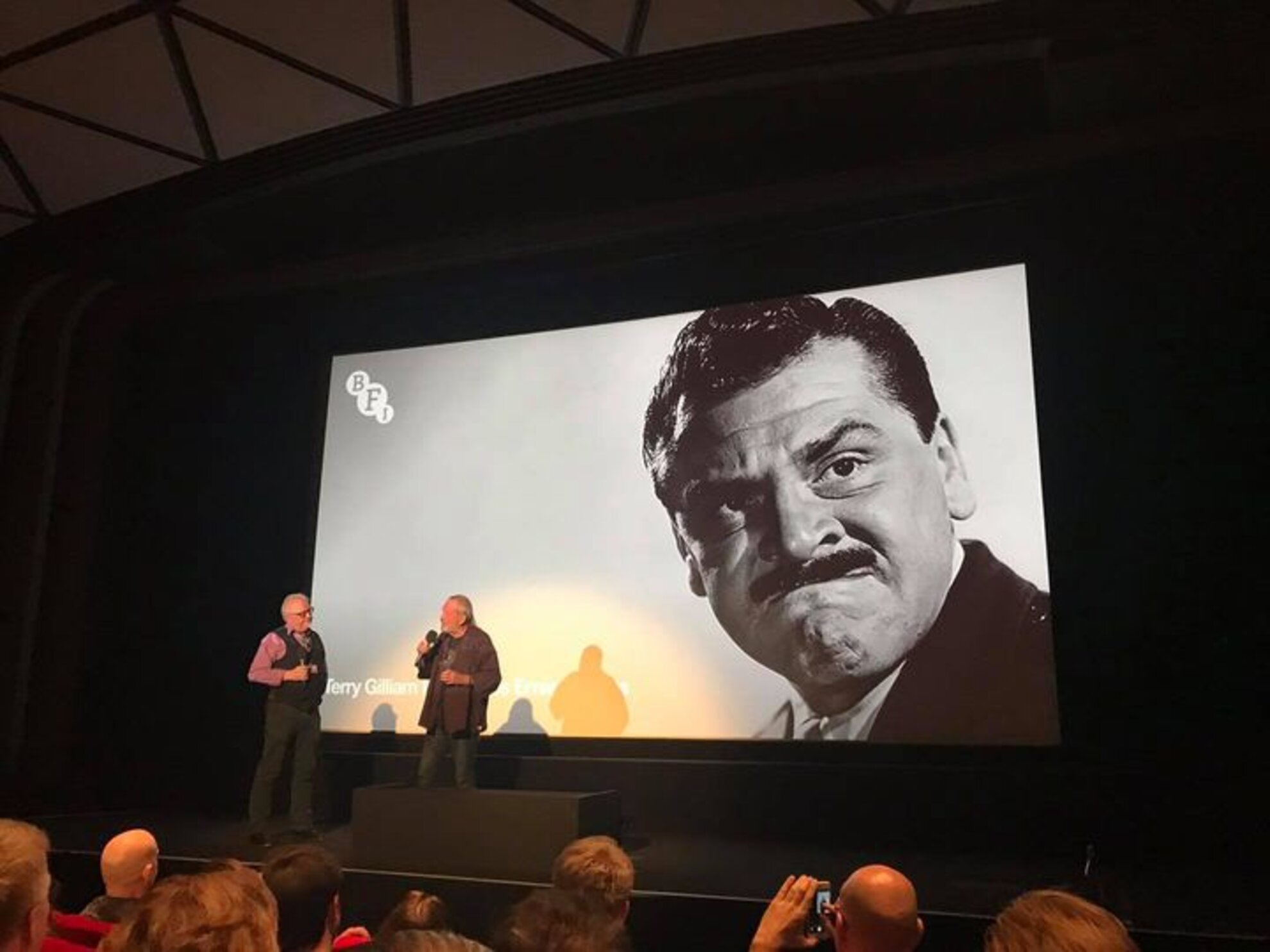

Many years later, Edie's son Josh met Terry Gilliam, the American member of the Monty Python team. “He told me he had invited the Python crew to the Paley Center,” says Josh, referring to the media museum in New York holding stacks of Kovacs material in its archive. “He said to them: ‘Now I’m going to take you to see someone you’ve stolen from all these years and you didn’t even know it!’”

Ernie in Kovacsland

Ernie in Kovacsland: Writings, Drawings, and Photographs from Television's Original Genius by Ernie Kovacs, Josh Mills, Ben Model and Pat Thomas

Published by Fantagraphics

Available from Amazon