If we had to sum up briefly what the collection of the Museum of Ethnography is about, we would say it is about us. It presents everyday people from varied cultures, and everyday objects full of life and stories. Through their exhibitions, we learn about general and culture-specific phenomena and thus get closer to our identity. We have seen countless proofs of this since the museum's opening: we gained an entirely new perspective on our most basic daily habits at the Ceramic Space, the ZOOM exhibition, and the Chair Pair exhibition.

And the recently-opened pop-up exhibition is no different. We are pretty sure that the time spent here won't leave you unaffected. Upon leaving, you might even put your warm beanie back on with a different mindset than ever before.

And the recently-opened pop-up exhibition is no different. We are pretty sure that the time spent here won't leave you unaffected. Upon leaving, you might even put your warm beanie back on with a different mindset than ever before.

The exhibition is also highly relevant because of the ongoing protests against the strict Iranian rules that require women to cover their hair with a hijab or Islamic headscarf. We can see how a 'piece of clothing' becomes the symbol of the fight for women's rights and freedom.

The theme selection is not a coincidence. The curator of the exhibition, Zsuzsa Szarvas, travelled to Iran during the early phase of the protests and thus, had been affected by this social issue on a personal level.

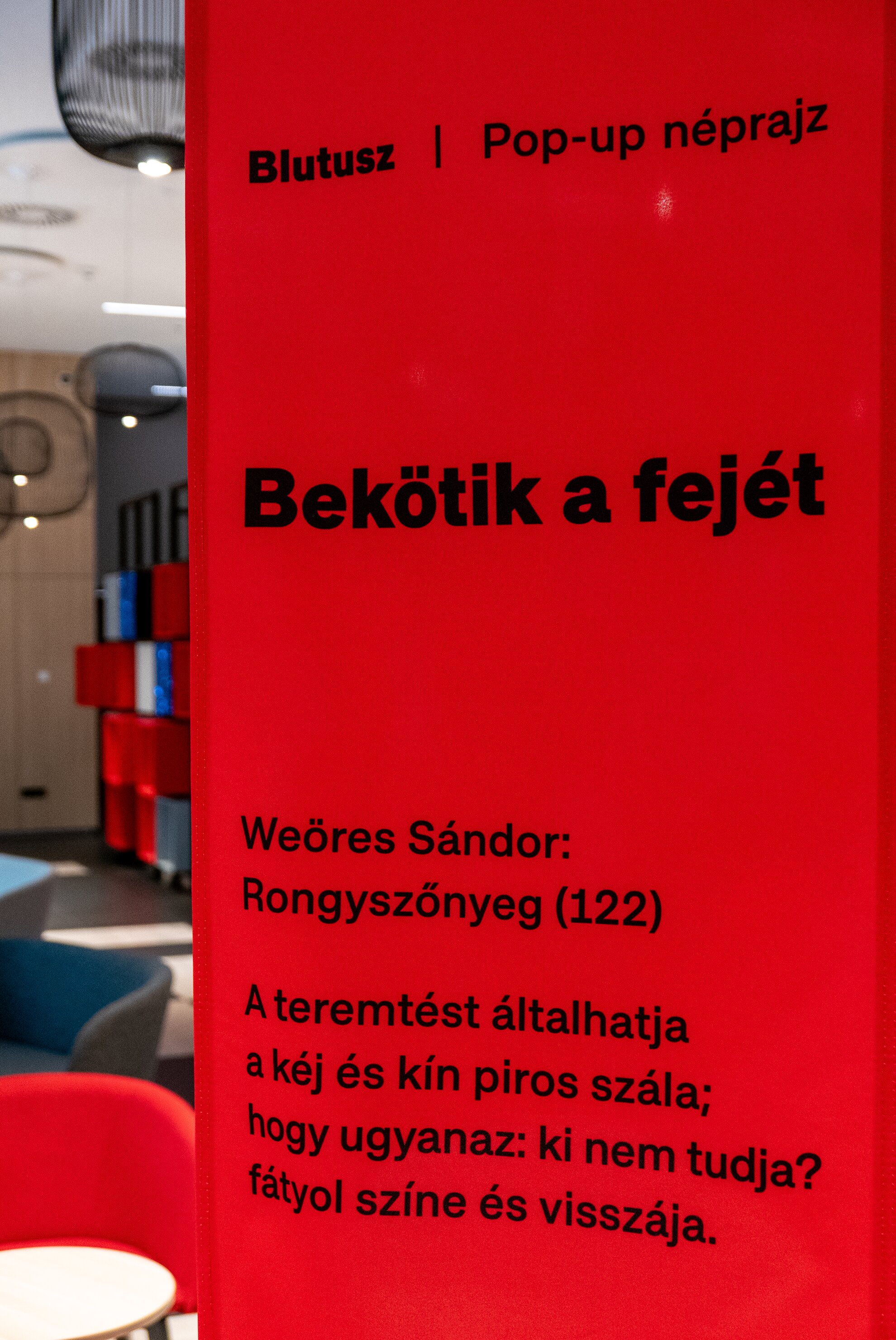

The exhibition includes only a few objects from the collection. Instead, the focus is on the dozens of photos that show the headscarf-wearing traditions and habits of women from European, Jewish, and Islamic cultures. The lively installations also present literary and contemporary art references, such as a poem by Sándor Weöres and a video installation by Luca Oberfrank. This broader spectrum is staying the guideline for future Blutusz exhibitions too.

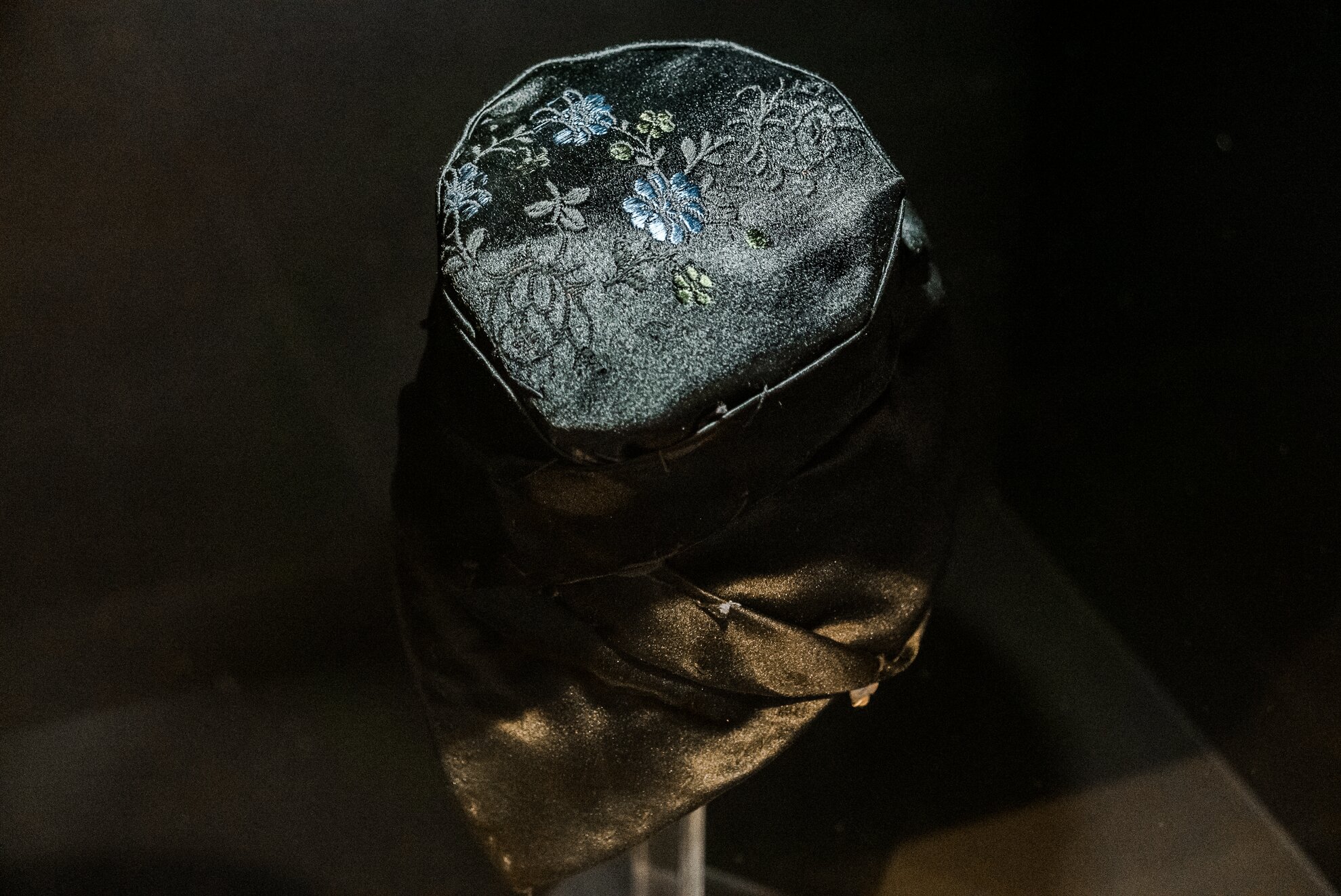

The tradition of wearing a kind of fabric to cover the head is almost as old as mankind: even Mesopotamians used scarves to protect themselves from the elements. This special piece of clothing is still present worldwide in the most diverse cultures, and sometimes they have similar meanings too. They can express belonging to a specific cultural or religious community. They can also indicate the age or social status of the wearer.

In the varied photos of the small but all the more thought-provoking exhibition, we see women smiling and being serious. We spot ordinary faces, which could belong to us. We admire the festive costumes of traditional peasants on their way to the church or smile at the familiar figures of the village aunties, heads covered with a headscarf. Thanks to the exhibition, we learn to guess what the dark colours of their clothes express. It is also revealed why Hungarians tell a bride to 'tie her head' when she gets married (a similar expression to 'tie the knot', but with a reference to scarves).

Seeing these strict systems, which were part of daily life in the countryside not so long ago, we immediately look at photos of women from other cultures more open-mindedly. We can see pictures of Jewish women in wigs and headscarves or Muslim girls and women covering their hair with colorful hijabs. We can also learn the difference between a chador and a burqa.

The exhibition does not intend to force any solution or interpretation on us. Still, it helps to discover our past, become more sensitive, and maybe even recognise ourselves in those living far away from us. This way, we can understand and accept others who voluntarily follow the tradition of their community with commitment. And we can also emphatise with those who wish to break out of a suffocating framework.

The exhibition is open between 14th December 2022 and 14th January 2024, and tickets can be purchased HERE.