Aptly named Every Past Is My Past, a major exhibition at the Hungarian National Gallery in 2019 not only presented the tip of a very big iceberg – 350 images from the vast archive of communal resource Fortepan – but also brought together the leading lights of a new project just launched in Budapest.

First established as the Hungarian-language Heti Fortepan, now reconfigured for English speakers as Weekly Fortepan, this enlightening discourse based around Fortepan’s photographic riches is the work of Capa Center curator István Virágvölgyi and Fortepan editor Miklós Tamási.

The inaugural English-language blog, published just before Christmas, focused on the work of Sándor Kereki. The current edition highlights the 30 favourite images of the 15,000 (!) uploaded by Fortepan over the course of 2021.

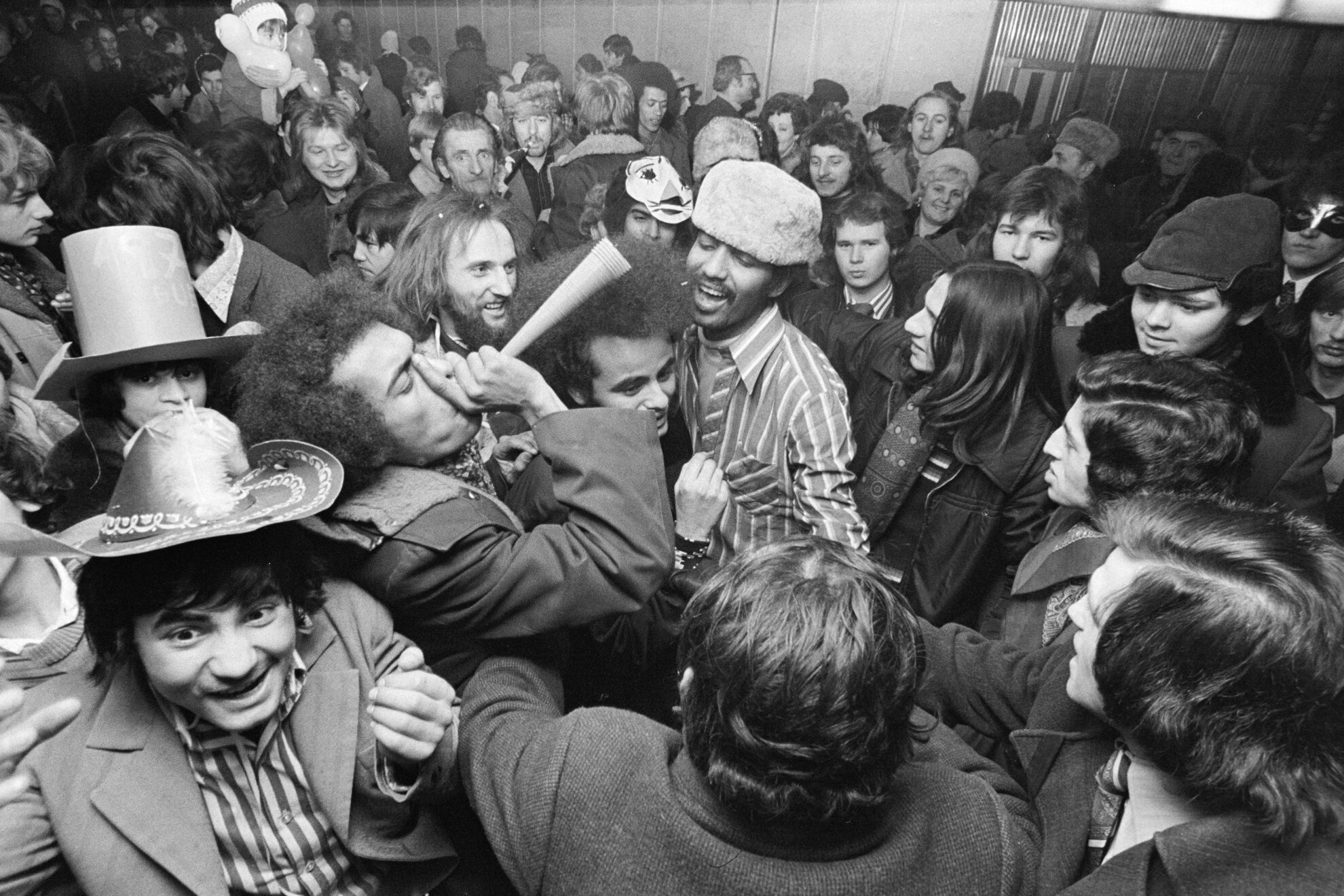

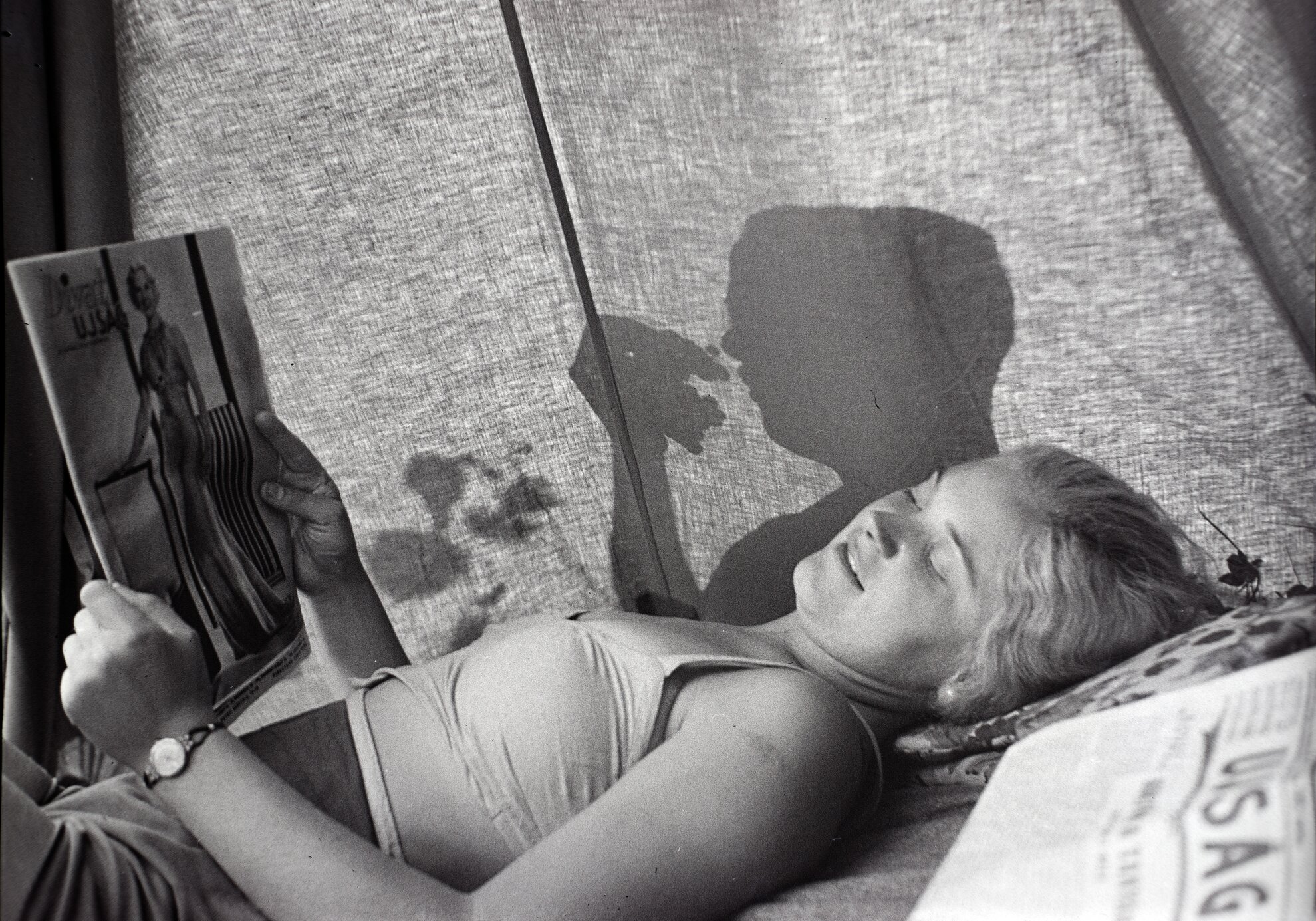

The now familiar Fortepan feel is evident throughout as Hungarians relax or pose, the date carrying as much weight as the image itself. A smiling girl reads a fashion magazine on a summer’s day in the late 1930s, uniformed men pose with sabres in 1918, Jews undertake labour service in 1940.

Ordinary lives, extraordinary history

As We Love Budapest reported at the time of Fortepan’s 2019 exhibition: “The pictures provide a glimpse into Hungarian history, with shots of bomb damage, soldiers from both world wars, grim-faced children in patriotically themed school pageants and tanks in the streets of Budapest in 1956. But simple snapshots from watershed years such as 1919, 1944, 1956 and 1989 serve as reminders that ordinary people were living ordinary lives while history went on around them. The everyday portraits, candid shots and past images of Budapest streets and Hungarian villages are the most compelling part of the collection”.

After their paths crossed at the National Gallery, István Virágvölgyi and Miklós Tamási realised that the fascinating work overseen by the Fortepan team required a wider platform.

“Just as the title of the National Gallery exhibition, Every Past Is My Past, came from a poem by Zsuzsa Rakovszky, the mission of the blog is to articulate the story behind the image,” says its co-editor, István Virágvölgyi.

“We also ask talented writers to run with a certain theme on a regular basis. It might be the colour red, it might be the strange sensation of being touched by a random stranger, a hairdresser, perhaps. This forum might also elicit more donations from the general public.”

There is certainly plenty of material to choose from. For the last decade, Fortepan, named after a revered type of negative film produced at the Forte factory in Vác, has been curating and publishing trove after trove of private family photos found in people’s sheds and lofts.

These random depictions of a shared heritage form the community-based archive free for anyone to browse and download. The only stipulation is that the photographer and Fortepan must be given named credits.

The collection is based on

some 5,000 images gathered from junk clearances around Budapest since the 1980s

and subsequent donations from 700 members of the public. These amateur snaps,

all taken pre-1990, are digitised and returned to their owners.

Miklós Tamási

and his team of a dozen volunteers sift through them and select those

considered to be significant from a social, historical or aesthetic point of view,

before uploading them onto the archive.

Around a third make the cut, adding to this growing resource. At the time of the 2019 exhibition, the images numbered 110,000, all dated and captioned. Today that figure is nearer 160,000.

“Many of the pictures are of outstanding quality,” says István, based at the Capa Center, the Budapest gallery named after the famous Hungarian war photographer.

Photographic devotion

“Not only in terms of composition but also their technical excellence. The amateur photographers of the earlier 1900s were devoted to their hobby. Glass-plate negatives provide high resolution, perfectly acceptable for use even today. They were really talented and understood photography.”

Quite often, a grandson or niece might discover a cache of pictures in a cupboard, the family oblivious to the fact that an older relative had been a keen photographer.

At present, the Fortepan concept of establishing a creative commons of images from public donations, diligently curated and captioned, is pretty much unique to Hungary.

István and Miklós are now seeking to broaden the project beyond Hungary’s borders, with interest from Poland, Romania and Malta, among others. Having been supported by various local foundations and non-profit forums over this past decade, Fortepan is looking for European funding to set up an international platform. The regular English-language blog, Weekly Fortepan, is a step in this direction.

Sign up!

Weekly Fortepan

Photos may be download in hi-res from the link at the bottom of the page – please credit the photographer's name and Fortepan.