Terrace restaurants line leafy Liszt Ferenc tér today, a leftover from the boom of the 1990s and early 2000s when this square was the place to relocate for café owners. Never hip, it was at least trendy for a while, before the tourists took over.

The beauty and atmosphere of this pleasant public space never went away, however, determined by the ornate, venerable buildings and large deciduous trees. You can sit in the middle, embraced by greenery, and not feel like you’re in the city centre at all.

The shape of Liszt Ferenc tér, more street than square, is no coincidence, for there was a wide street here, which gradually transformed into a square in parallel with the development of the city.

Some 250 years ago, this was the outer edge of Pest. At the time, the area did not yet have a name, nor any specific public status, until the Valero Silk Factory was built here between 1783 and 1786, bringing change to the locality

The

Valero family, which excelled in silk and veil production, moved from Spain to the

Banat, today in western Romania, and from there to Pest. Here in the late 1700s,

an impressive, castle-like, two-storey factory was built according to the plans

of Mátyás Zitterbarth Sr, which started urban development around what is now Liszt

Ferenc tér.

The area gained its first name in 1785, Fabriken Gasse (’Factory

Street’), which it carried for a generation until in 1850 it was translated

into the Hungarian Gyár utca, although Valero had moved his factory from here

in 1839.

The oldest residential building on today’s square, the late Classicist corner house at No.7, was built in 1860, whose historic value is enhanced by the fact that it was actually built on the foundations of an even older, one-storey residential house.

Trees were planted here from 1810 onwards. As a result, in the early 1870s, a small park was established at the Andrássy út end, whose two two-metre-high ornamental fountains, designed by Miklós Ybl of Opera House fame, were opened in 1885.

When town planners had other ideas, the fountains were removed in 1904. One was taken to a courtyard in adjoining Jókai tér, another is no longer with us. In its place came a statue of 1848 revolutionary Dániel Irányi, which stood here until 1948. It was then transported to Károlyi-kert, where you can find it today.

Getting

back to Franz Liszt, in 1907, the former street became a square. That same year,

the new building of Liszt’s Music Academy was completed in Art Nouveau style on

the site of the former Institute for the Blind. This provided the perfect

opportunity to rename the space, as the composer had been the first director of

the conservatoire.

At that time, today’s Jókai tér, the other side of Andrássy út,

was also part of Liszt Ferenc tér. The statue of revered writer Mór Jókai was unveiled

there in 1921 and, four years later, in his honour, this small annexe of Liszt

Ferenc tér gained its independence.

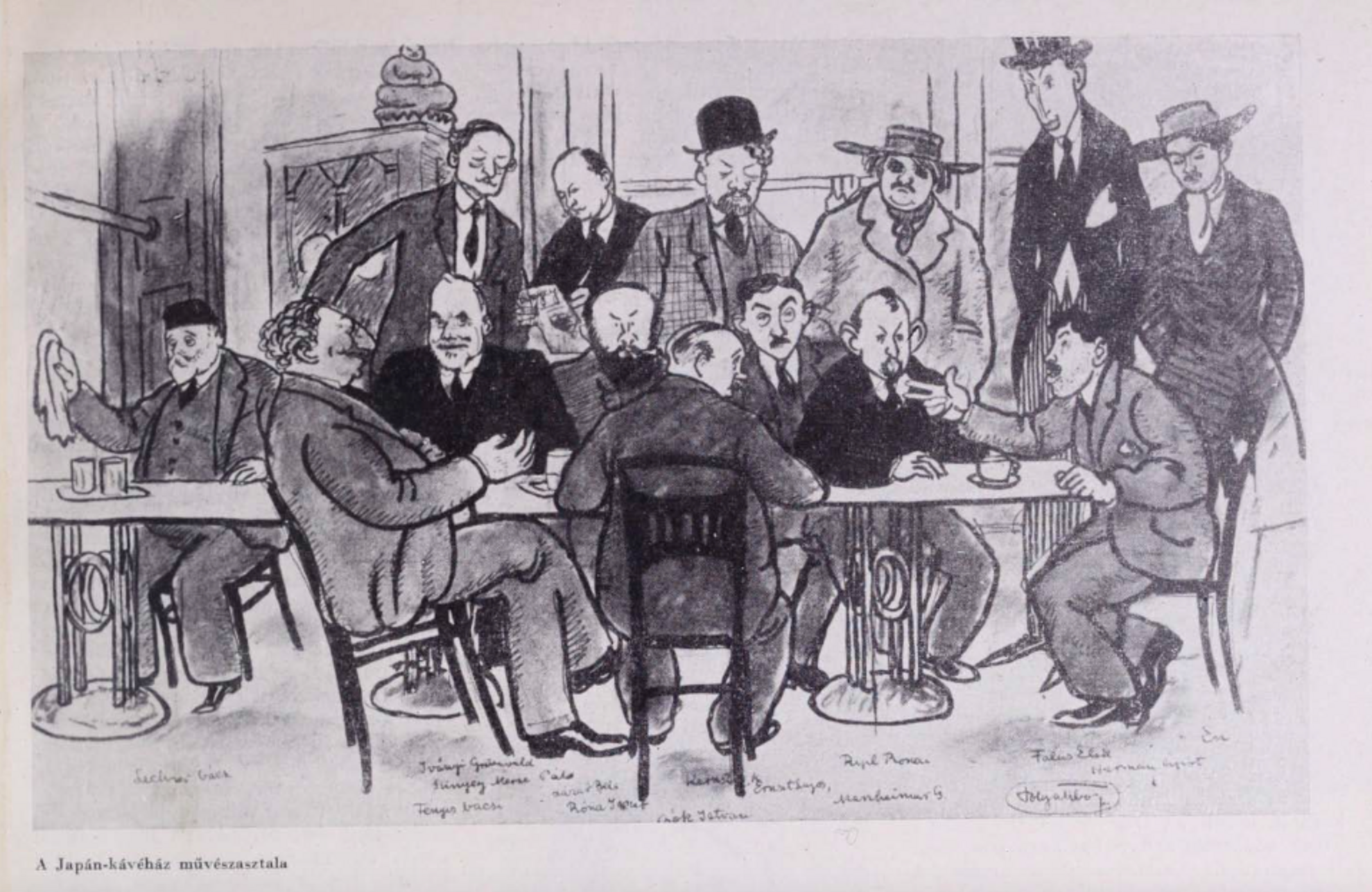

Back then, the Japán Kávéház on the corner of Andrássy út was in its heyday, attracting major figures from the world of art and literature such as Lajos Kassák and Jenő Rejtő, while Ernő Szép, József Attila and Sándor Bródy lived at Liszt Ferenc tér 11. Today, this is the Írók Boltja, the Writers’ Bookshop, which hosts literary launches and readings.

The green tram and trusted grannies

In the 1920s, there was also a public toilet on the square, a green

building that resembled the first trams in both colour and shape, so locals

called it the zöld villamos, the green tram. Another curious feature could

still be seen, or rather heard, in the 1960s – this was where the city’s

last street scales stood. This wasn’t a speak-your-weight machine so much as a

speak-your-weight granny, an old lady whose palm you had to cross with 30

fillér in order for her to tell you how heavy you were, using her vintage

contraption.

In 1936, the master of Art Nouveau, Ödön Lechner, was another figure to receive his own statue but, like Irányi’s, this also only stood here until 1948. Lechner was taken to the garden at the Museum of Applied Arts, considered the architect’s masterpiece. As Lechner had little political baggage attached, it may be asked why the new Communist authorities deemed the move necessary. It turns out they were planning to build a bus station here, and the two statues were in the way.

Thankfully, the plan never materialised, although a small petrol station

appeared here in the late 1950s. In 1960, a statue of national poet Endre Ady was

erected on the Andrássy út side of the square and, in the mid-1980s, Franz

Liszt himself at last received his rather dramatic likeness, created by László

Marton, József Finta and László Szlávics Jr.

Two more sculptures were put up in

recent times, of poet Attila József and, during the major renovation of the Music

Academy in 2013, of conductor György Solti.

By then, the square had been closed to car traffic, and it was lined on both sides with restaurant terraces, mainly patronised by the new in town and the undiscerning.