To provide context for its latest exhibition, the Kiscelli Museum, whose mission is to illuminate anthropological history over the centuries, shows the role the toilet has played in culture. Classic examples, shown in photo and video form, include Marcel Duchamp’s Dadaist urinal, Frank Zappa in excretory mode and Ewan McGregor clambering out of the murk in Trainspotting.

There’s also the scene from Géza Bereményi’s 2002 film Hídember in which

the hero, the tirelessly inventive Count István Széchenyi, presents an English flush

toilet to a partly astonishing and partly sceptical aristocratic audience. The tragic

nobleman may have built the Chain Bridge but he also designed modern bathrooms for

the family mansion at Nagycenk.

More recently, in Game of Thrones, the unseemly

death of Charles Dance as Tywin Lannister gives some idea as to the nature of the

smallest room in medieval castles.

The exhibition has been laid out like a multi-level dungeon with several rooms underground, the visitor exploring the dark tunnels of history. The most exciting elements, sprinkled with abundant cultural and historical material, are the contemporary objects and furnished rooms.

In the Roman Empire, the apex of ancient democracy, citizens relieved

themselves with ease, sitting alongside each other in communal outdoor toilets,

amid lively banter.

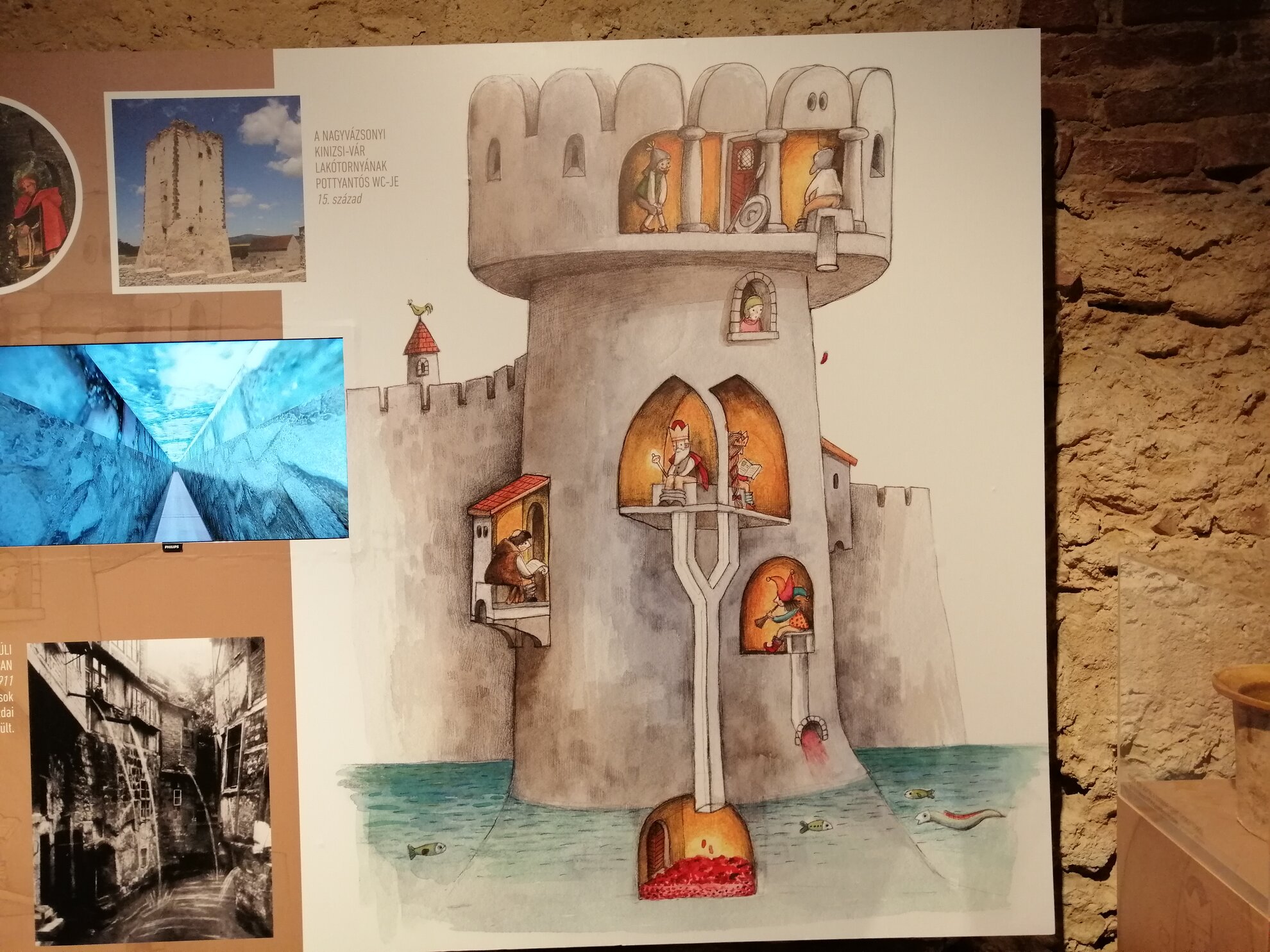

In the aforementioned medieval castles, drop-in booths lined

corridors and spiral staircases, end result falling into the surrounding moat,

whose stench must have been horrendous.

You can also trace the development of wiping devices. While pieces of leather and rags were used in medieval castles, the Romans had a trough full of vinegar water and a single brush or sponge in the middle of the communal latrine, which everyone used to scrub themselves clean.

The most peculiar object is the bourdaloue, a kind of Georgian-era she-wee, a long-shaped jug which women, dressed in layer after layer of clothing, used to relieve themselves when in company.

The lack of shame and limited intimacy associated with this basic human function, considered as natural as eating, ran until the 1800s. Everyday language was full of phrases, proverbs, expressions and parables related to toilets – Flemings were particularly inventive – but these slowly died out as societies became more prudish.

The last third of the exhibition deals with the modern age and its toilets. Here, in addition to cultural-historical curiosity, retro comes into play. You can see how bathrooms looked in the Socialist era, there are photos of public conveniences closed only recently and a display of Crepto toilet paper, used by generations of Hungarians, elicits a strange kind of brand loyalty in locals.

The exhibition is both exhaustive and entertaining, and should satisfy the most curious of visitors. Although documentation is in Hungarian, the dates shown and objects presented should provide a pretty clear idea in any language.

Exhibition information

Klóaka, Kanális, Klozet

Kiscelli Museum

District III. Kiscelli utca 108

Trams 17, 19 & 41 to Szent Margit Kórház then steep walk up Kiscelli utca

Until 26 September, Tue-Sun 10am-6pm

Admission: 1,600 forints/discounted 800 forints