Pharoah Amenhotep II

Pharaoh Amenhotep II was a member of the 18th dynasty, as was his father,

Thotmes III, a legendary warlord also known as Napoleon of Egypt, whose empire

he inherited.

Initially, Amenhotep waged campaigns, but after realising that he

could not surpass his father’s successes on the battlefield, he turned to state

organisation and nepotism, deftly manoeuvring his childhood friends, former

teachers and family members around an empire that stretched from present-day

South Sudan to the Euphrates.

In the first part of the exhibition, visitors are given an idea of the pharaoh’s reign, organisation and personality. An image unfolds of a hard, athletic and competitive ruler who loved physical sports and fast horses, rowing and running, and who loved to be portrayed as a sound administrator with a strong physique and peaceful face, as carved on one of the decorative stelas.

Egyptologists should be congratulated for being able to recognise the depictions not only on the basis of the hieroglyphs and various attributes of power they illustrate, but also on the basis of facial features.

The image of a peaceful administrator is also strengthened by the fact

that at the beginning of Amenhotep II’s reign, he made no radical changes,

slowly replacing the leaders of his highly respected father's apparatus.

These

positions were otherwise held by the Sons of the Cape, the Egyptian upper

class, and the court institution responsible for educating the children of

certain foreign princes. One of the most interesting pieces in the exhibition

is a life-size copy of the chariot found in his grave belonging to Kenamon, the king’s

milk brother, breast-fed by the same noble mother.

There is much to be said about the nature of absolute power, that although we know much about the lives of Egyptian privileged, we know almost nothing about how the lower classes and the poor lived. At the exhibition, visitors can become acquainted with the items of furniture, clothes, dining implements and funeral customs of the upper classes.

An upscale two-storey home, its public and private functions clearly separated, was lit with lanterns or elegant, beautifully crafted candelabra, had many rugs and ornate boxes of various sizes. Clothing was not over-exaggerated, the cloaks and scarves of the nobles came into fashion later, and the almost stereotypical huge wigs were worn only for celebrations.

Great care was taken to cleanse and treat their bodies with balms and oils, and a strong unisex make-up painted with extract of malachite or galena, not only served beauty purposes, but also protected from the sun.

Loret the explorer

The second part of the exhibition jumps a few thousand years from the Pharaohs’ court to the period of the 1898 discovery of the tomb. The heroic age of Egyptology is difficult to assess today as so much is overshadowed by the swift and powerful effect on art and culture of the discovery of Tutankhamun II in 1922 at a burial site near Amenhotep;s, in the Valley of the Kings.

The special aspect of the earlier find is that Amenhotep II was that the first pharaoh was found in his own resting place, in his sarcophagus. Although the tomb had been looted in antiquity, it was tidied up as early as the first millennium BC, and mummies of nine neo-imperial pharaohs in their coffins were also brought here, further increasing the importance of Loret’s discovery.

The global fame of Amenhotep II

The news of Loret’s find also spread around the world. Contemporary Hungarian newspapers reported, referring to Amenhotep’s Greek name: “Oh happy Amenophis II! Of the so many kings, all of whom sought to bury their mummies in the depths of inaccessible hiding places forever, he is the only one left in his stone tomb – that’s why it’s so overcrowded in the mourning halls,” wrote Budapesti Hírlap.

Loret did an excellent job considering the technology available to him, of documenting the stages of the excavation quite precisely and with astonishing humility. Much patience was required as the rooms leading to each chamber had to be excavated one by one, and the whole job completed step by step. The temptation to go further without being so thorough must have been overwhelming.

The chamber & mementos of the afterlife

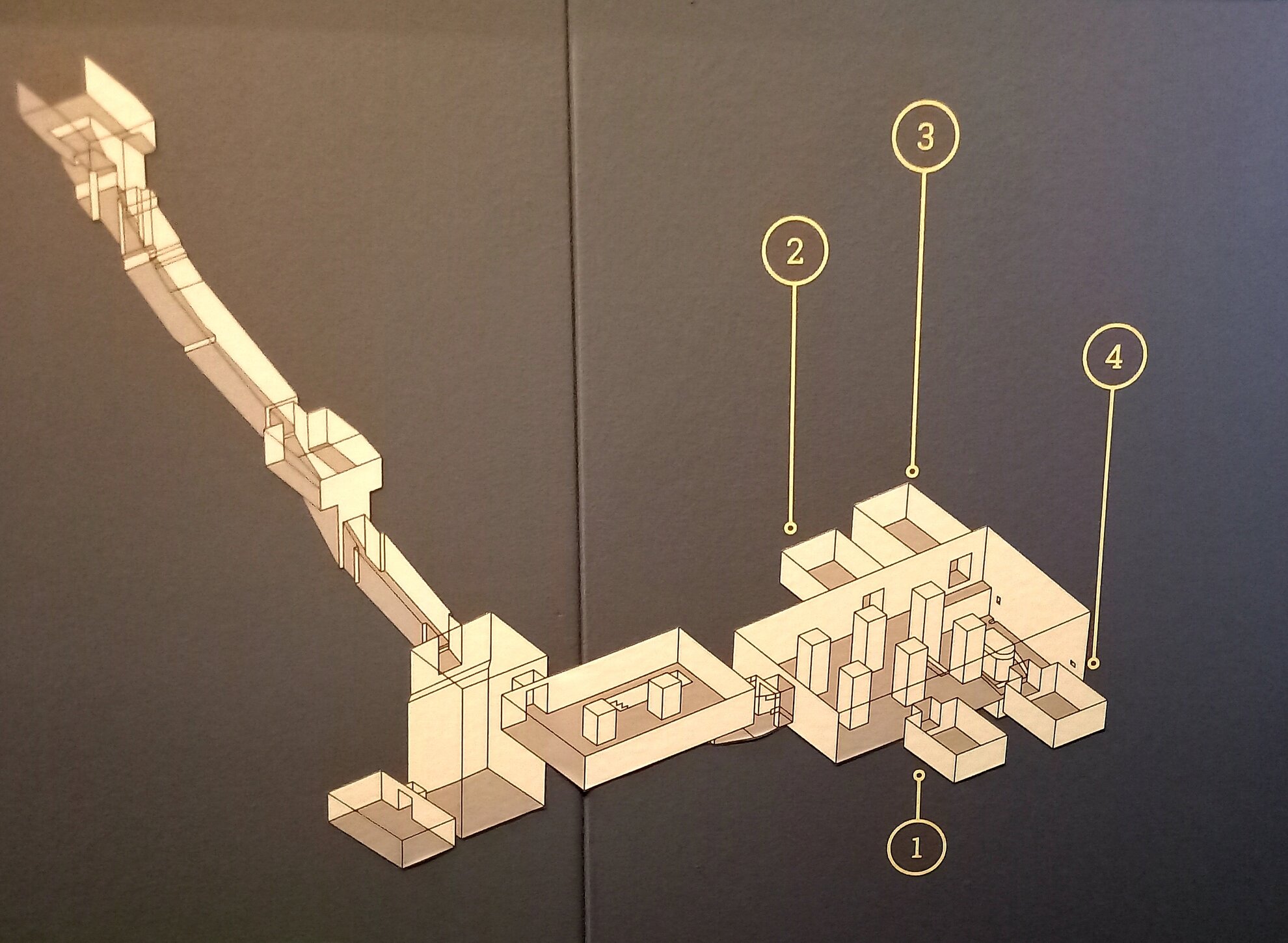

After learning these fascinating details, the visitor then accesses a life-size copy of the tomb. The installation is extremely exciting, as you have to negotiate a zigzag maze, feeling like a tomb robber or an explorer such as Loret.

From the floor plan of the original tomb, which can also be seen, you surmise that the beautifully decorated room here was the centre of the burial site, surrounded by four smaller side rooms with the other nine mummies.

Particularly amazing are the earthly remains of a young woman who,

according to genetic tests, may have even been Tutankhamun’s mother, and whose

face is distorted by an injury that may even have caused her death.

Stepping into the rest of the tomb, you are struck by the wonderful harmony of golds and blues, the subtle proportions tailored by the six ornate columns. The decorations showcase the events depicted in the Amduat, a book about the Egyptian afterlife.

According to this, the sun god visits the afterlife at midnight, and on his way, he is accompanied by the dead pharaoh for rebirth. The story begins behind the sarcophagus and continues on the walls in a clockwise direction. The ceiling of the chamber was decorated with blue and gold stars, typical of pharaohs’ tombs of the period.

The rest of the exhibition shows the funeral customs of the nobility and perceptions

of the afterlife in Ancient Egypt. Several theories exist, but the fullest

possible preservation of the deceased's earthly body and the rituals around it determined

their possibilities in the afterlife.

Initially, the tombs were decorated with

objects used in life or with copies of them, while later the elements intended for

otherworldly use became more and more important. The inhabitants of the tombs

were, for the most part, the resting places of men, women and children.

This is the first major exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts since

lockdown, and it complements the material from the 2017 Milan

exhibition on Amenhotep II. This also borrowed from the British Museum and the

Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, here augumented with material from institutions in

Brussels, Italy and Copenhagen.

An excellent catalogue is also available.

Exhibition information

Museum of Fine Arts

1146 Budapest, Dózsa György út 41

The Discovery of the Pharaoh’s Tomb

Open: Until 9 January 2022, Tue-Sun 10am-6pm

Admission: 3,600 forints, discounts 1,800 forints