The great seaplane boom took place after World War I, when civil aviation began to advance. These types of aircraft could take off and land on water, and proved popular until World War II.

Cumbersome seaplanes could not compete with PanAm’s faster and safer long-range Boeing 314 Clippers, flying boats produced from the late 1930s onwards. By the late 1940s, the seaplane was just a fad.

They appeared in Hungary relatively quickly,

and large-scale plans were drawn up for these amphibious craft to ply the

Danube. Aéroexpress was a joint Hungarian-German venture. On the Hungarian side, the founders were noblemen, Count Endre Jankovich-Bésán, and on the

German side, the aircraft and engine manufacturer, Junkers in Dessau, which was

in its heyday in the 1920s.

Founded in 1923, the company had ambitions to

become a major player in air transport, not only domestically but also abroad.

Right from the start, Aéroexpress

received licences for three routes: from Budapest to Prague, to Székesfehérvár,

Nagykanizsa and Zagreb, and to Bucharest. However, with the exception of

Austria, it wasn’t possible to reach agreement with the other neighbouring countries.

Domestic air transport from Budapest for 5,000 crowns and the Budapest-Vienna

line remained. Seaplanes would travel back and forth several times a day, transporting

aristocrats and wealthy citizens to and from the Gellért Hotel & Spa, then both under

the same umbrella and the most prestigious lodging in town.

Sadly, this was not enough for the ambitious plans or the long-term future of Aéroexpress, not even with the addition of a Munich flight towards the end of the story.

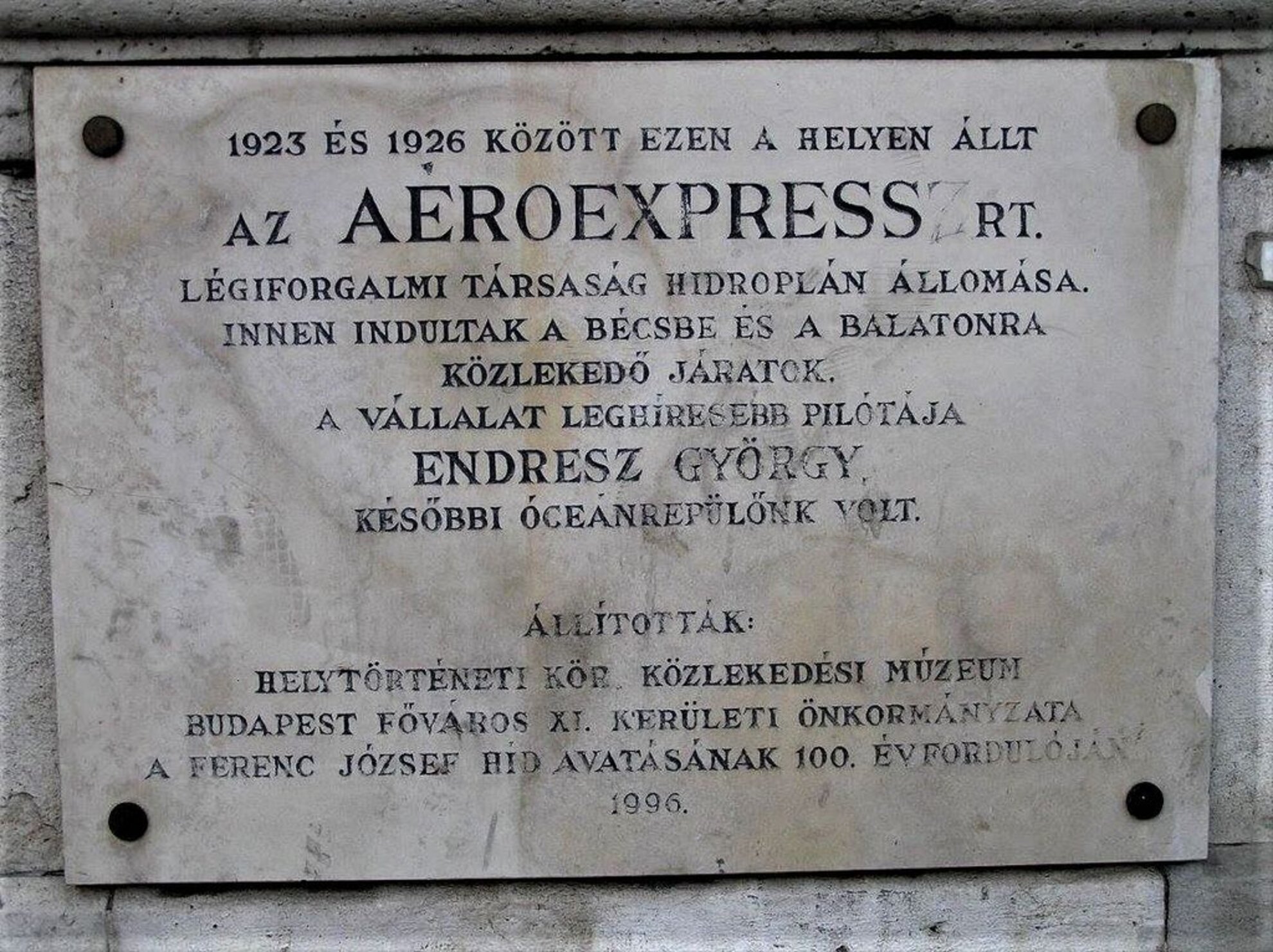

The company’s airport, founded in 1923,

was at the Buda end of Liberty Bridge, then known as Franz Joseph Bridge. They

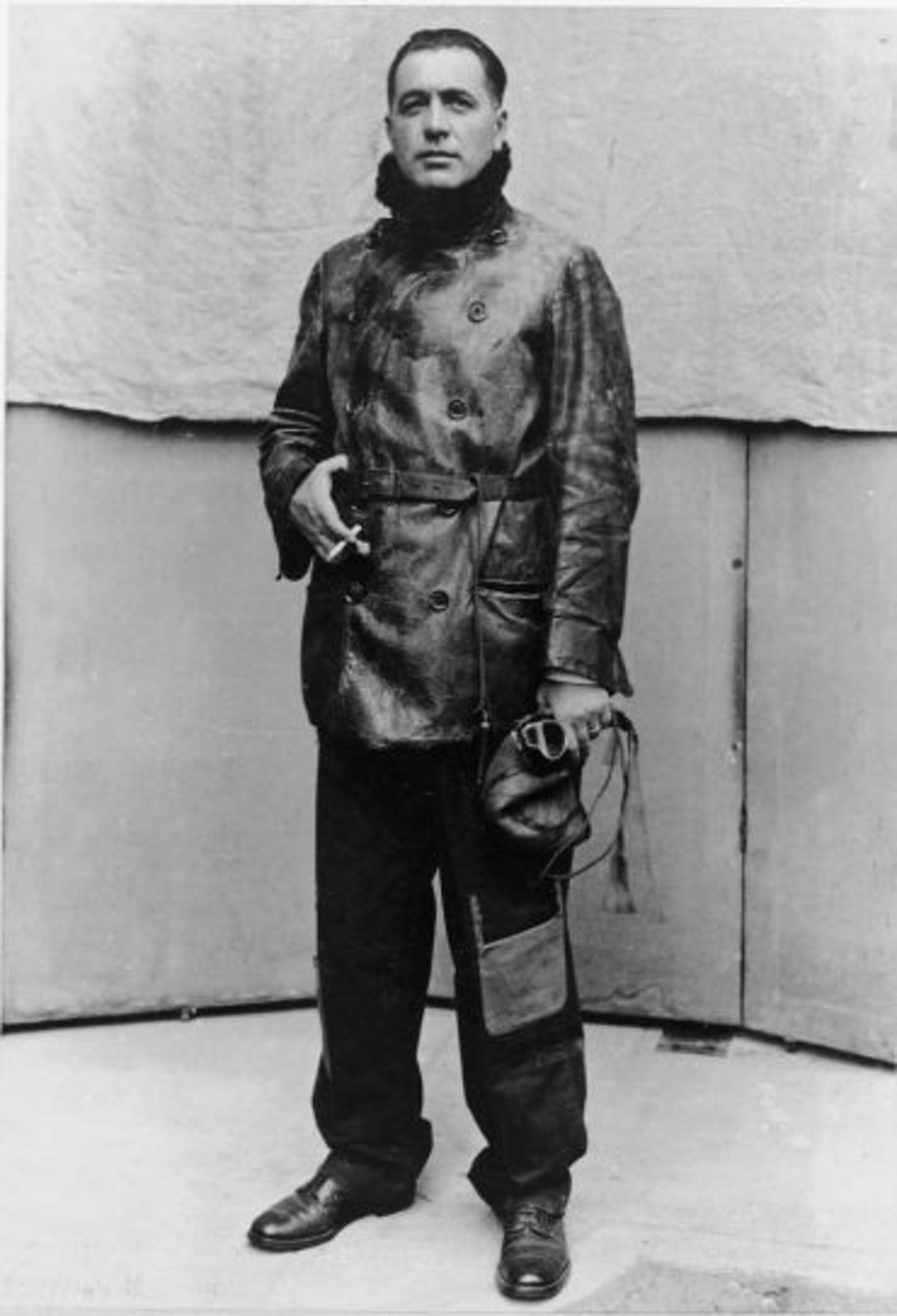

soon signalled their ambitions by engaging one of the famous Hungarian pilots

of the age, György Endresz.

He had gained a considerable reputation

for himself during World War I and, although an active member in Hungary’s

subsequent and short-lived Soviet Republic as commander of the Red Squadron, he

was still able to join Aéroexpress a few years later.

It wouldn’t last long. Aéroexpress was

forced to close its seaplane station in 1926, and in 1930 the company also

ceased to exist. Endresz remained a pilot for Junkers – he was also an

instructor for the Aéro Association – but only until 1932.

The airman had gone

to Rome for a meeting of the world’s ocean pilots, but his plane crashed on

landing, The 39-year-old Endresz and his navigator both died immediately.

We do not know whether Aéroexpress failed to take off due to bad business policy or poor neighbourly relations, but even if the planned routes had been undertaken, the heyday of the seaplane would only have lasted another ten years or so. What if they would have reached agreement with Boeing? We will never know.