There was a square on the site of Dísz tér long before the arrival of the Turks in the mid-1500s, although it did not quite look like it does now. Where the Honvéd monument stands today was the site of the Chapel of Szent György, founded by King Lajos in the mid-1300s, from which the square took its original name.

There were also two gates at separate points in the square, closing it in: the one named after Szent János opened to the east, later known as Vízi kapu (‘Water Gate’) and then much later Franz József kapu, and the Jewish (later Fehérvár) Gate facing west.

The German quarter of the city of Buda was located in this part, and Dísz tér initially functioned as a market. Then it was given another function: executions.

The most famous beheading here should have been that of prominent nobleman László Hunyadi in 1457, but King László V, fearing rebellion, relocated it, and timed it for the evening when there was hardly anyone around.

Later, King Matthias erected a statue in the square in honour of his brother. Today it is no longer visible, and was probably destroyed by the Turks.

The famous event in Hungarian history linked to the square was the peasant uprising led by György Dózsa. It was here that he began his crusade, which eventually developed into an insurrection against the nobility. The Archbishop of Esztergom, Tamás Bakócz, who started the campaign, lived on the square. He gave a rousing speech from his balcony and then presented the army flag to Dózsa in a ceremony at the nearby Church of Szent Zsigmond.

Of course, if he had known the horrific fate which would later befall Dózsa and his followers, the mass tortures and his brutal execution on fiery throne, he may not have given his blessing.

There is almost no remnant left of Turkish times although, according to contemporary accounts, this space was thoroughly remodelled. The Chapel of Szent György became a mosque, with smaller ones also built here, and a long covered bazaar reaching as far as today’s Matthias Church. The former German produce market was also revived.

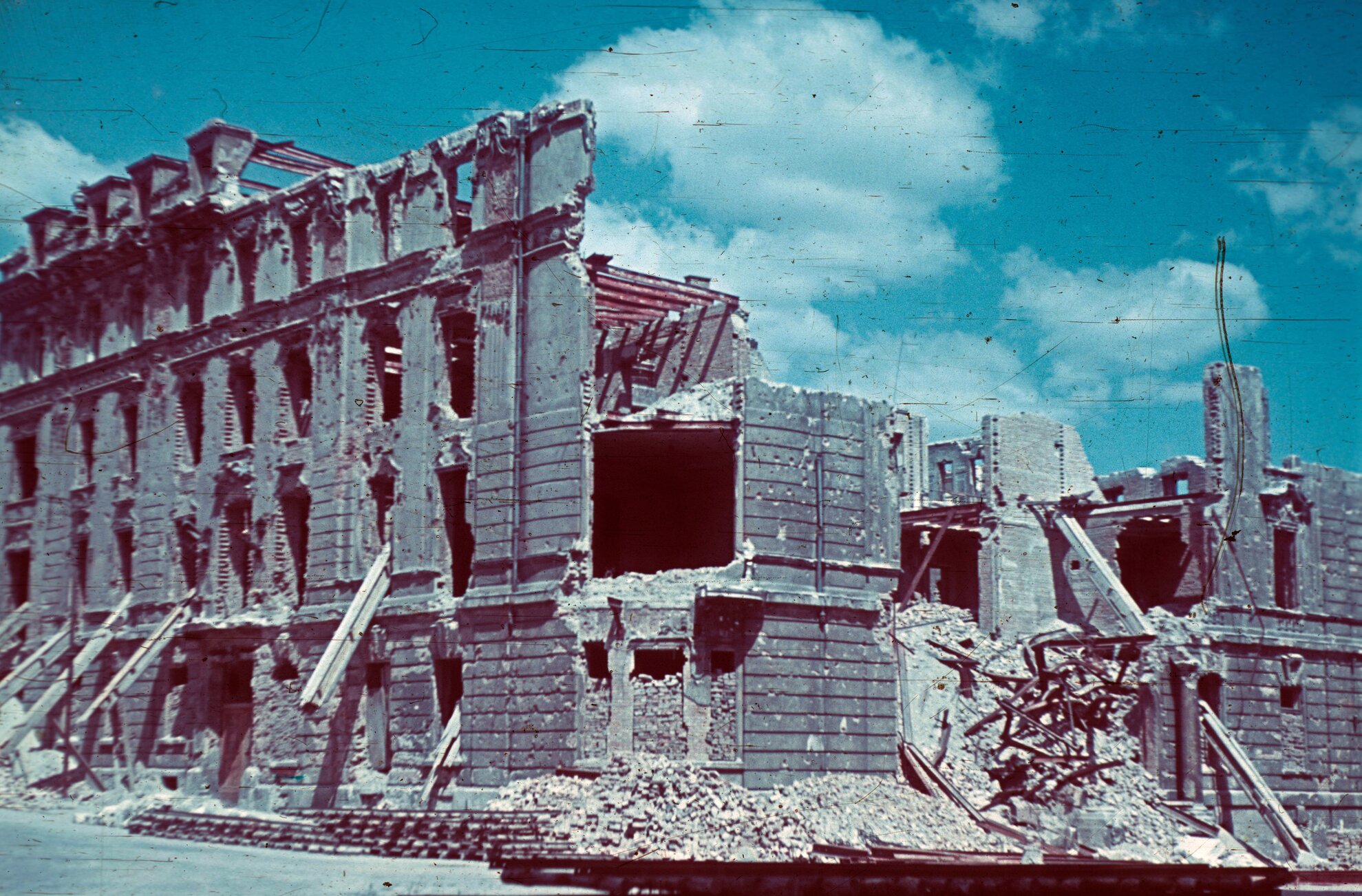

Then came 1686 and with it the liberating armies, who on the one hand drove out the Turks and on the other hand, demolished most of the houses lining the square. More change was to follow.

Two smaller churches had also stood here since the Middle Ages and, to increase space, they were also knocked down. The new Austrian rulers rebuilt the residential houses here in Baroque style, with a touch of Classicism added in the late 1600s. The so-called General Guard stationed here were tasked with protecting the gates at both ends of the square.

As military demonstrations and parades were held here at that time, the area gained paramount importance, so in 1718 it was given the name of Fő tér (‘Main Square’). Due to the regular parades of the guard of honour, it was given the name Dísz tér in 1728, when, in addition to military inspections, executions were still held.

In the 1730s, Serbian Orthodox believers sparked an uprising because they were being forced to convert to Catholicism. The rebellion was crushed and its leaders summarily dealt with in the square before a significant crowd. Later, the number of executions decreased.

Later that century, an important change took place: around 1785, a large ornamental fountain was built here. Though it no longer exists, this defined the image of the square, which had had a rural feel up to then.

This changed by the time of the so-called Reform Era between the 1820s and 1840s. The Honvéd monument, designed by György Zala, was erected in 1893 to mark the occupation of Buda in 1849, and it later became a popular meeting place for locals, as it is today.

In the earlier 1900s, the former house of the aforementioned archbishop Tamás Bakócz operated as the Foreign Ministry, forced to move towards the end of World War II. The Batthyány family owned several houses in Dísz tér, some of which can only be seen in photographs.

But there were other famous inhabitants of the square. Fin-de-siècle writer Ferenc Móra, who lends his name to a small side street, once lived here, as did János Passardy, pioneer of silkworm breeding and silk production in Hungary. Archbishop Angelo Rotta was the papal envoy who represented the Vatican in Hungary here between 1930 and 1945.

Another important building on Dísz tér is number 16: in the 1700s, it housed Buda’s first pharmacy, first known as the Golden Unicorn, changed to the Golden Eagle Pharmacy. Today, it’s a confectionery.

Following the destruction of World War II, restoration was slow and gradual, and including the construction of a modern residential house incongruous with the former surroundings.

During the war, the caves beneath Buda Castle operated as a series of bunkers and air-raid shelters, a narrow-gauge railway connecting important ministries with the Prime Minister's Office. This underground network remains untouched to this day, inaccessible to local residents.