Traditional Hungarian clothes ranged from the practical – sheepskin jackets, durable trousers – to the lavishly ornate, full of intricate motifs and designs. The four regions of Hungary – Transdanubia, the Great Plain, Transylvania and Upper Hungary – had their own distinctive styles, and each could merit a full article here in their own right.

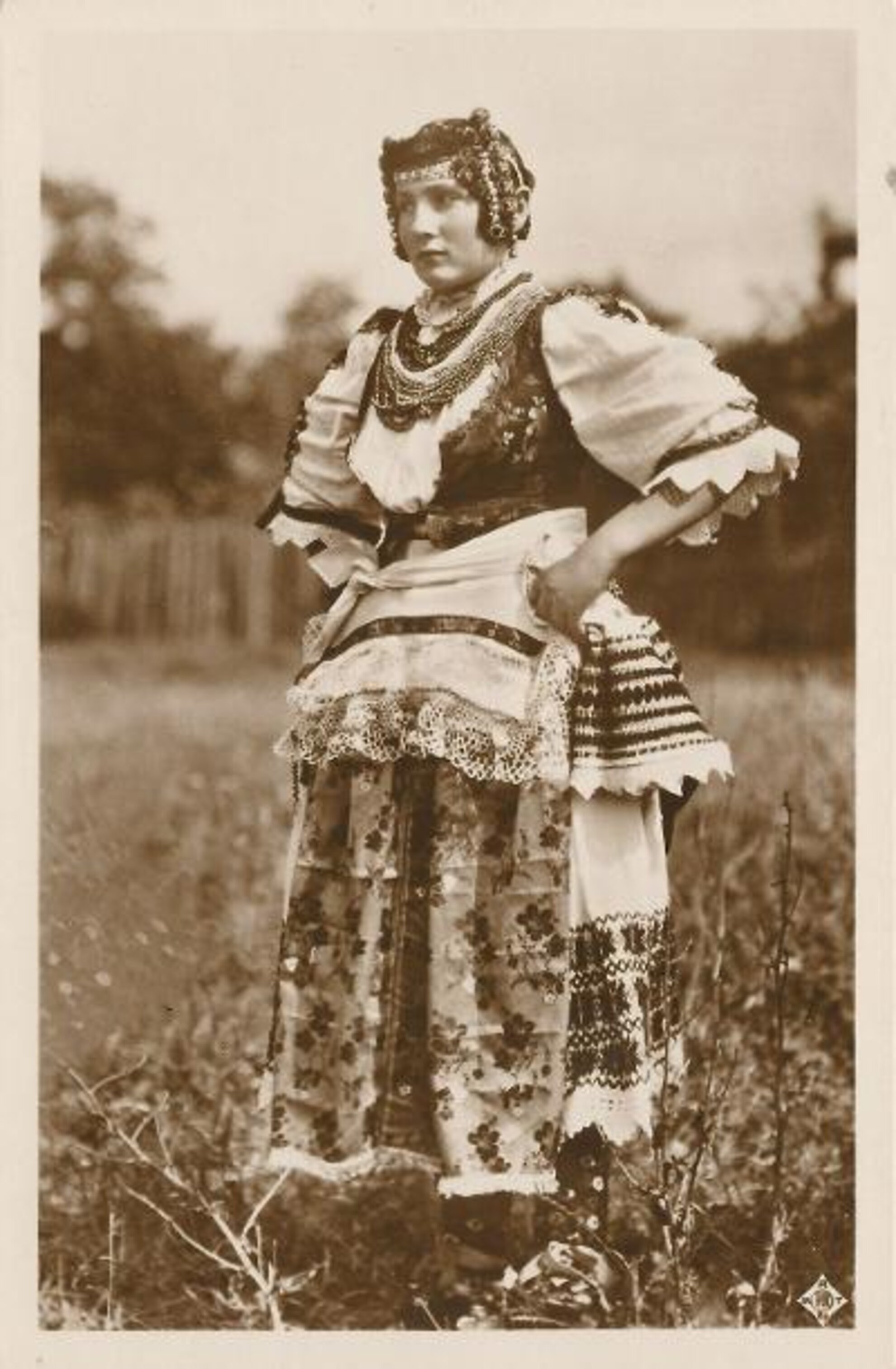

While the fashion could vary even from village to village, there were some general consistencies. Women and girls wore layered skirts, short blouses and special headdresses, which denoted their marital status, and men sported some sort of shirt and vest or overcoat, trousers, and a hat or fur cap. Before industrialisation, fabrics were painstakingly dyed by hand, and limited to natural pigments including red, yellow, green, blue or brown. Weekday clothes were more rustic – white, grey and brownish – although these so-called peasant colours were cheaper, and indicated a lower social standing.

Once it became easier to produce brightly-coloured materials, the traditional Hungarian wardrobe became awash with new possibilities, including red, pink, purple, yellow and the deep indigo which became known as kékfestő. Interestingly, black was considered highly festive, due to its association with the bourgeois, being expensive to manufacture. Sometimes, it was even used for weddings and, by contrast, white was associated with mourning.

Today, we’re likely to see traditional costumes still worn by locals for special celebrations such Busójárás in Mohács. And kékfestő, which is recognised by UNESCO, is still sold at fairs, festivals and markets, striking because of its rich colour and intricate patterns.

Another famous Hungarian hallmark is that of Matyó embroidery, which can be can be traced back more than 200 years, from an area in eastern Hungary known as Matyóföld ('Matyó land'). According to legend, the Devil kidnapped a young man from the area, and wouldn’t release him until his bride paid the ransom: a bundle of red roses. As it was the middle of winter, the request was impossible – but the clever girl embroidered the roses onto her apron instead, and the Devil liked her handiwork so much that he set the bridegroom free.

There’s even a saying in Hungarian which sums up the embroidery’s significance: when a piece of clothing fails to be fashionable or stylish, a Hungarians might say it's nem egy matyóhímzés (“not a Matyó embroidery”).

Colours and ornaments signified many aspects of daily life in the traditional Hungarian wardrobe. Just observing the feather or plume stuck in a man’s hat could tell you whether they were married, of age, single, taken or a bachelor. Girls wore wreaths, ribbons, or corollas – a type of circular headpiece – and housewives wore close-fitting caps, known as coifs. The married women changed their coifs throughout their lifetimes, indicating their age, status and even whether or not their children were married.

Over time, the decorations became truly flamboyant, and the extra laces, ribbons, pearls and spangles became known as glitterings. Not only the wealthy, but the poor also strove to incorporate these lavish decorations into their costumes, to the chagrin of some. In fact, in 1925, the town of Mezőkövesd created a bonfire out of glitterings in the main square, burning them in public to protest their traditional folk art being overwhelmed by these incongruous glitterings.

Even the menfolk participated in these extravagant styles. In the Great Plain region, Hungarian men were commonly seen wearing a high-topped, narrow-brimmed hat, decorated with feathers. A black sleeveless waistcoat was usually worn with a sheepskin jacket, and special occasions called for wide, flowing sleeves rich with embroidery.

Those in Upper Hungary tended to dress a little simpler, with a dark suit, outerwear and boots. The male festive outfit may still have included an apron, and this was embroidered along the bottom.

In modern times, the rich traditional outfits of Hungary have passed more or less into obscurity. Elderly people might still be seen in villages wearing these clothes during festivals or special occasions, but they are a rare sight. Nevertheless, certain motifs live on, tied into mainstream fashion trends, such as embroidered jackets or scarves.