Now approaching his 70th birthday, János Kőbányai was motivated to suggest a retrospective of his work to the Műcsarnok while visiting an earlier photographic exhibition here with his daughter. Perusing the famous faces of Hungarian theatre, the theme of the event, she delivered this damning verdict: “It’s so boring, Dad!”.

This convinced her father to approach the cultural director of the Műcsarnok. A positive response then persuaded this self-taught photographer to delve into his archive, 10,000 strong, with the help of noted art historian Zoltán Rockenbauer.

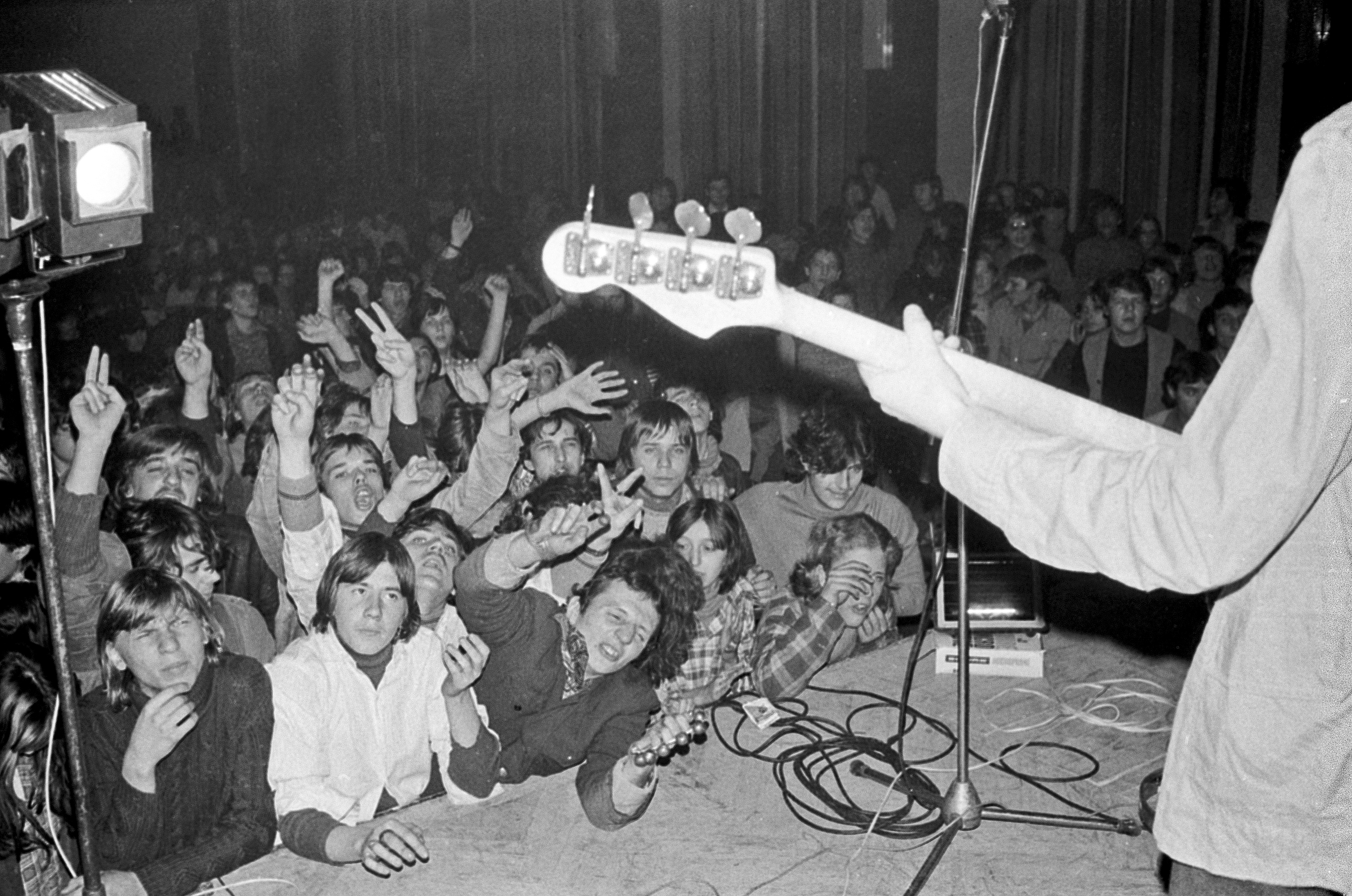

The collaborative result is anything but boring. Presented semi-samizdat, semi-fanzine style, many of the 200 mainly black-and-white images would not have looked out of place on posters and picture sleeves in any record shop in the UK circa 1978. Bands thrash away at guitars, crowds crush around the stage in acclaim, musicians relax backstage, at house parties and even at home.

For these seminal years, János not only recorded but was integral to this scene. “I was always asking photographers to take images of the bands I was writing about,” says this law graduate-cum-writer.

Have camera, will travel

“Someone at the magazine then suggested I take the photos myself. From then on, I always had my Olympus and my notebook with me. I couldn’t imagine writing about a group and not taking pictures, or snapping the band and not writing about them.”

A law graduate whose father worked at leading local daily Esti hírlap, János was diverted from his career path as he roamed the festival sites, cultural centres and long-forgotten live venues of Budapest. Catching the tail end of the so-called Beat Era that began in the 1960s, János also hung on to coattails of punk as this more direct form of anti-Communist rant was barked out.

Both generations fell foul of

the authorities – that was pretty much the point, certainly as far as the spikier

gang was concerned – but there was no great divide between the two movements as

was clearly delineated in the West.

As the viewer strolls from one room to the other

at the Műcsarnok,

from hippy to punk, heinous crimes of fashion (Gábor Presser of LGT seems to have spent an entire decade in

dungarees, a hanging offence in the UK c.1977) give way to a then alternative

look. Denim turns to leather, flares to drainpipes, lending the exhibition one

of its underlying themes: csöves, meaning

both the straight-cut trouser legs of punk lore and a ne’er-do-well, still Hungarian

slang today.

János himself seems more

attuned to denim, creating entire monochrome tableaux of what he terms Budapest’s

Woodstocks, the outdoor Tabán festivals every May Day. Another image shows him

hitchhiking back into Hungary from the Austrian border, a soup-plate Jim

Morrison badge covering an entire lapel, having made it all the way to London

in the seminal summer of 77 only to see… the Troggs.

He’s also seen here

remonstrating with stern men in grey suits unhappy about some of the images he’s

posted up in a student dormitory – a student dormitory, mind, not a

gallery – in 1982. Fittingly, this shot is entitled Generations on the

Margin – English/Hungarian documentation is excellent throughout the exhibition,

with all dates and locations given.

It wasn’t long before the big beat groups – Omega, Piramis, Illés – were playing big stadium arenas. One shot frames Lajos Illés dwarfed by the iconic floodlights and sweeping tribunes of an empty Népstadion the morning of a major show there in 1990. Another captures a granny wielding a carrier bag surrounded by rocking long-haireds while Piramis blast out Újpest’s football ground.

What he terms a sociographer by vocation, picking up on societal shifts and transitions, János instinctively grasped that the ecstatic, often extreme, facial expressions and body language of the audience were just as interesting, certainly pictorially, as whatever rock rituals were being played out on stage.

Turning rebellion into energy

“For me,” explains János, “what music was inspiring across Hungary and Poland was even more important than in the West. Here, we had no voice, we had no vote. This was how we could channel our energy”.

Yes, János prayed at the altar of the Marquee after hitching to London but he knew exactly why banned band Beatrice mattered to Magyar youth.

The most interesting elements

of Beat Fest are neither the festivals nor the live shows but the underground

happenings involving an ever edgier bohemian fraternity of artists, musicians

and filmmakers, often offshoots of the influential Szentendre set.

Just as

award-winning Hungarian director Miklós Jancsó is captured at work on set with the

musical icons of the beat era, so these ad hoc get-togethers in random rooms

and back gardens reveal a cultural crossover more significant than just three

chords churned out by malcontents.

One particular event merits highlighting, partly because it spawned one of the signature photographs of the collection, of János before his own exhibition in 1979 in the shabby back garden of a cultural centre in Budaörs, arms splayed, tongue out. Moments later, the covering behind him was torn down by attendees and his images beneath ripped off the wall by the crowd in a spontaneous gesture of performance art.

Soon, everyone would be

draped in nylon and soaked in blood-hued watermelon – this was August – as

characters in strange garb sang or read spoken-word verse, all filmed and shown

here on a loop, though sadly without the soundtrack.

Next door, meanwhile, presumably

the neighbours in Budaörs were sitting in front of the TV, watching Socialist-era

soaps, blissfully unaware of the craziness over the garden wall.

Normality is another key theme. The first image in the worthwhile 72-page catalogue (2,300 HUF) accompanying the exhibition shows rocker Ádám Török in his leather jacket in 1977, dutifully tucking into the soup and grilled meat his mother had prepared for him as she stands over the table willing him to eat it all up.

These were also innocent

times, when there was little difference between band and fan – everyone

lived in the same circumstances, drank the same undrinkable Hungarian beer of

the day and were under few illusions about the opportunities open to them.

The only colour images in the show, a poignant bookend, are dedicated to great LGT bass player/multi-instrumentalist Tamás Somló, his funeral and the farewell concert in his honour in 2017.

János himself ended up in Paris, where a night at the opera inspired him to abandon rock for arias, before diverting yet again to put his sociographic skills to work in essays, books and film scripts.

With his own publishing company here in Hungary, Múlt és Jövő (‘Past and Future’) he now returns after several years studying Jewish history at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, eager to complete his unfinished novel, Beat-kór régény. If it carries anything like the excitement of his photographs, it shouldn’t be a boring read.

Beat Fest

Műcsarnok

District XIV. Dózsa György út 37

Open: Until 3 Jan 2021, Wed-Sun 10am-6pm

Admission: 1,000 HUF, reduced 500 HUF