André Kertész, a 20th-century Hungarian-born photographer, is renowned for his contributions to photographic composition and photojournalism. While many know him for his iconic works captured in Paris and the US, a new exhibition at the Hungarian National Museum invites you to explore his roots. The 'Kertész / Copies' offers intimate glimpses into his relationships with family and friends, as well as various locations in and around Budapest.

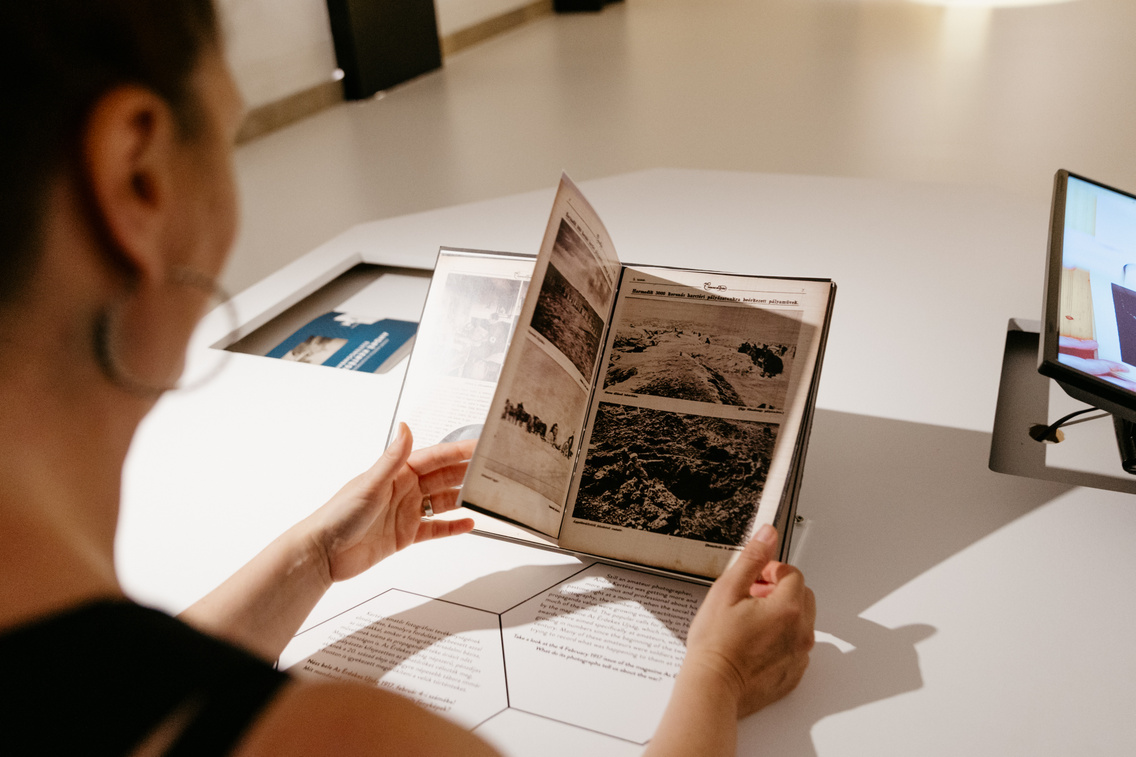

In 2021, 1,163 photographs arrived in Budapest from New York, showcasing images taken before Kertész left Hungary. You can now see them at the Kertész / Copies exhibition, which is more than a documentary of an era – it is a record of an artist’s development and self-discovery, addressing fundamental questions in photography. What environments and human connections shaped the young Kertész? How and why did he use the camera? How did war, nature, and ultimately photography alter his perception? What are the multiple meanings of intimacy? At the Hungarian National Museum, we can find our own answers to these questions by following the young André Kertész.

The Photographer in Search of His Path and His 'Voice'

The National Museum's exhibition focuses not on the established artist, but on the young man born in Budapest 130 years ago. This is a portrait of a childhood spent in the city's eighth district, summers with relatives in the countryside, and the vast landscapes traversed as a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Love affairs, war, and the mundane routine of bureaucracy shaped this period, as did his close relationships with family and friends.

Kertész's early photographs of Budapest reveal a personal connection to the city. Rather than iconic landmarks, he captured the everyday life of Teleki tér, Kálvin tér, Népszínház utca, and the Tabán neighbourhood. Venturing beyond the city centre, he photographed the Buda Hills and the Csepel Island area. By the 1920s, his professional eye was drawn to the suburbs of Budafok, Rákosfalva, and Pomáz. Water was constantly present in his work, from the Danube's flow through Nagymaros and Esztergom to the Romanian town of Bralia. With his brother Jenő, he was a regular visitor to Budapest's Danube baths, capturing the dynamic interplay of swimmers, light, and shadow.

A fascination with movement had emerged early, evidenced in his photographs of races and football matches from the 1910s. His engagement with avant-garde art circles in the early 1920s further developed this interest. He has always been fascinated by movement and the relationship between man and water.

The war, a crucible of suffering and camaraderie, was a profound experience. While initially documenting his comrades for their loved ones, his focus shifted to capturing human emotion and detail.

His earliest subjects were family and friends, but even these portraits reveal an experimental spirit. A turning point came in 1925 with a self-signed studio portrait of his uncle, marking a transition from amateur to professional. A series of enigmatic 'half-cuts' likely sent by his love, Erzsébet Salamon, offers a glimpse into their tumultuous relationship. Their story, marked by separation and reunion, is intertwined with the evolution of Kertész's photographic style.

Don't just look, feel it!

The exhibition is divided into two main sections, differentiated by colour and light. One half, transitioning from light to dark and culminating in a dark room, represents the young Kertész's 'arrival' in photography, charting his journey from amateur to professional. The lighter section is interactive, prompting visitors to consider various themes through Kertész's images.

For example, by peering through small apertures, we can explore the diverse world of intimacy, which extends beyond sexuality to include mother-child, father-child, and friendship bonds.

Evidence of his beekeeping passion is found in a hive-like display.

The exhibition's highlight is a montage by Kertész, composed of paintings created between 1913 and 1923 before his emigration to Paris. The selection of these particular works as milestones is intriguing. Visitors can create their own digital montage of Hungarian amateur photographs from this period, saving their results.

Vintage copies and 'stickybacks'

The exhibition introduces key technical concepts. Vintage copies refer to positive prints made from original negatives, often contemporaries of the original photograph and attributed to the photographer. These are highly valued in the art market.

The others are 'stickybacks', small-format portraits, often among Kertész's earliest works, featuring himself, family, and friends.

More details and tickets here.

(Cover photo: Forgács Zsuzsi – We Love Budapest)