Following the 2018 reopening of a Jewish bath and the prayer house on Táncsics Mihály utca in the Castle District, further medieval finds may yet be discovered. For decades, the ruins of a Buda synagogue have lain untouched below ground. Inspections are ongoing and excavation may begin this year.

The first Jewish quarter was established in the Castle District following

the Tartar invasions of the 1200s. A synagogue was built where Palota út meets

Dísz tér, on the site of today’s Korona Kávéház.

Its remains were discovered in

2005, but due to its specific location, it is unlikely that it will ever be explored. The quarter was liquidated in the time of King Sigismund,

around 1420, due to the construction of the royal palace.

The situation is different with the largest Gothic synagogue, in the

second Jewish quarter. It was built in 1461 by the Jewish prefect Jakab Mendel

at what is today Táncsics utca 23, and may have been the largest Israelite

church in Europe.

During the Turkish occupation, everyday life in the community

was relatively undisturbed. This ended with the Siege of Buda in 1686 when Christian

armies slaughtered the refugees in the synagogue and then set the building on

fire.

Their remains were later buried, only to be found within these walls by archaeologist

László Zolnay in 1964. Without the necessary permits, he could not proceed with

full excavation, so the ruins were reburied and sealed with a concrete slab.

Towards the end of 2020, these were examined by experts at the Budapest History Museum. For some 20-30 years, no one had touched the site and, in the absence of documentation, it must have been filled with sand for the purpose of stability. According to archaeologist Ágoston Takács of the BHM, only after this sand is removed can a feasibility study be carried out, and a decision made on how to proceed.

Currently, a listed building stands at Táncsics Mihály utca 23, the Baroque Horányi-Zichy Palace. The synagogue lies buried in the courtyard, some

four or five metres below. Zolnay excavated a short section of its two

longitudinal walls in 1964, which is only a small part of the whole synagogue.

Complicating matters is the fact that its southern wall coincides with the base

of the palace façade – in the 18th century, they simply built on top of the

synagogue walls. On the side facing the castle wall, the base of the synagogue

stretches alongside.

According to Takács, they might survived in such good

condition because they were built upon, and they feared that the rest of the

U-shaped structure will be in a worse state. The annexes may not be found, for

example, such as the women’s prayer room, which may be beneath today’s

residential building. On the other hand, it is quite certain that the area

still holds valuable artefacts, as the collapsed synagogue has been buried as one

whole.

The house and plot are the property of District I, and contain municipal rented flats. The courtyard is densely planted with trees, and removing them might be a sensitive issue. There’s even a dilemma about the stability of the house itself, but a decision on excavation is due soon.

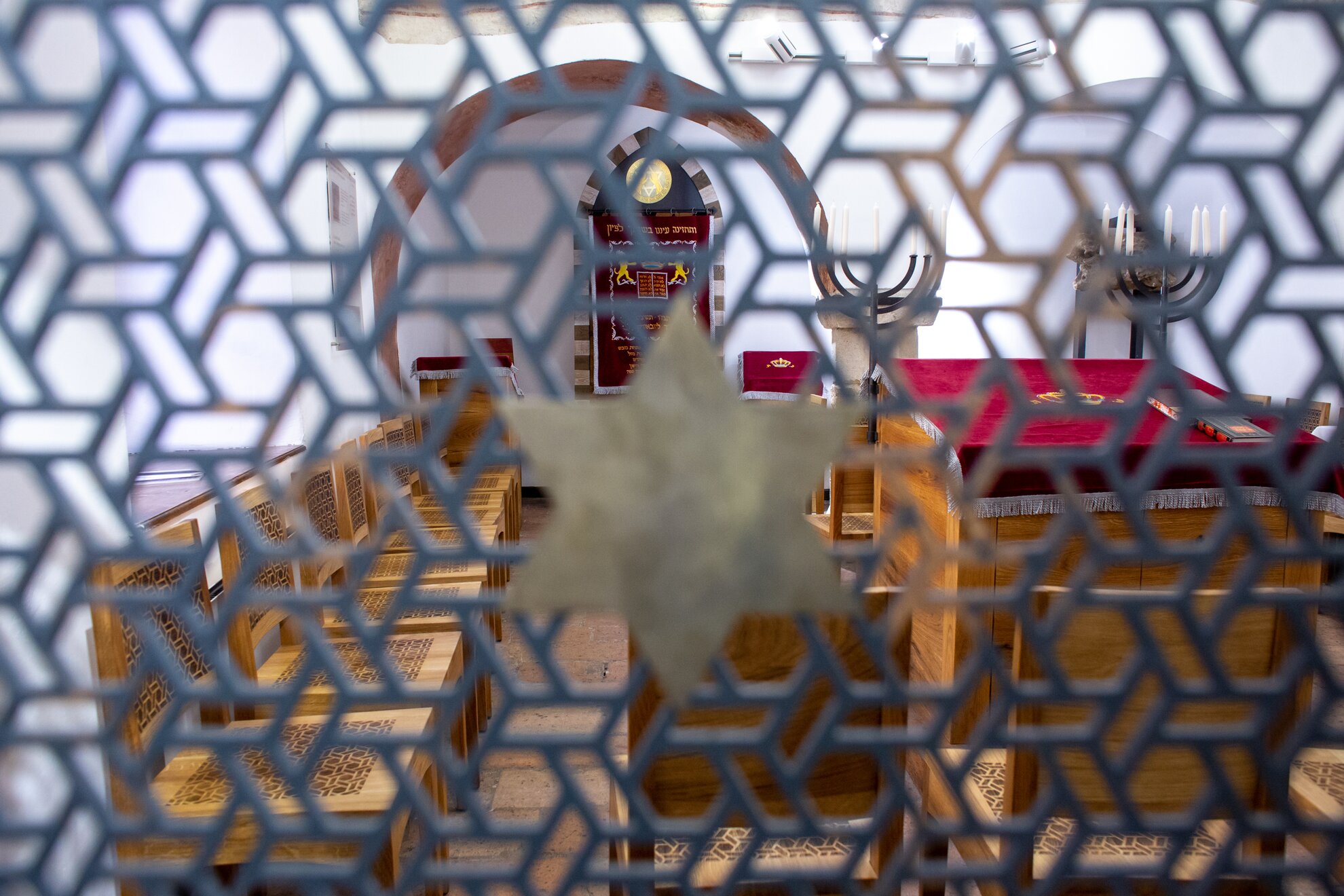

Opposite, on the other side of the street, is another smaller prayer house from the same era, discovered in 1968 during post-war reconstructions, and which regained its original function in 2018. It has been operating as a house of worship ever since, while the mikva, or ritual bath, nearby is also open to visitors in normal times.