Oh, you neon-bright Budapest! Nostalgia is a dangerous thing, sweetening bygone eras and soothing us with the sentiment that things used to be better. And yet we are drawn to images of retro Budapest, especially to the incredible neon signs which used to fill the streets with light. Once a prominent profession, their manufacture can still be admired with pictures showing how these fluorescent tubes were made – and we also take a look at the best examples still shining throughout the city.

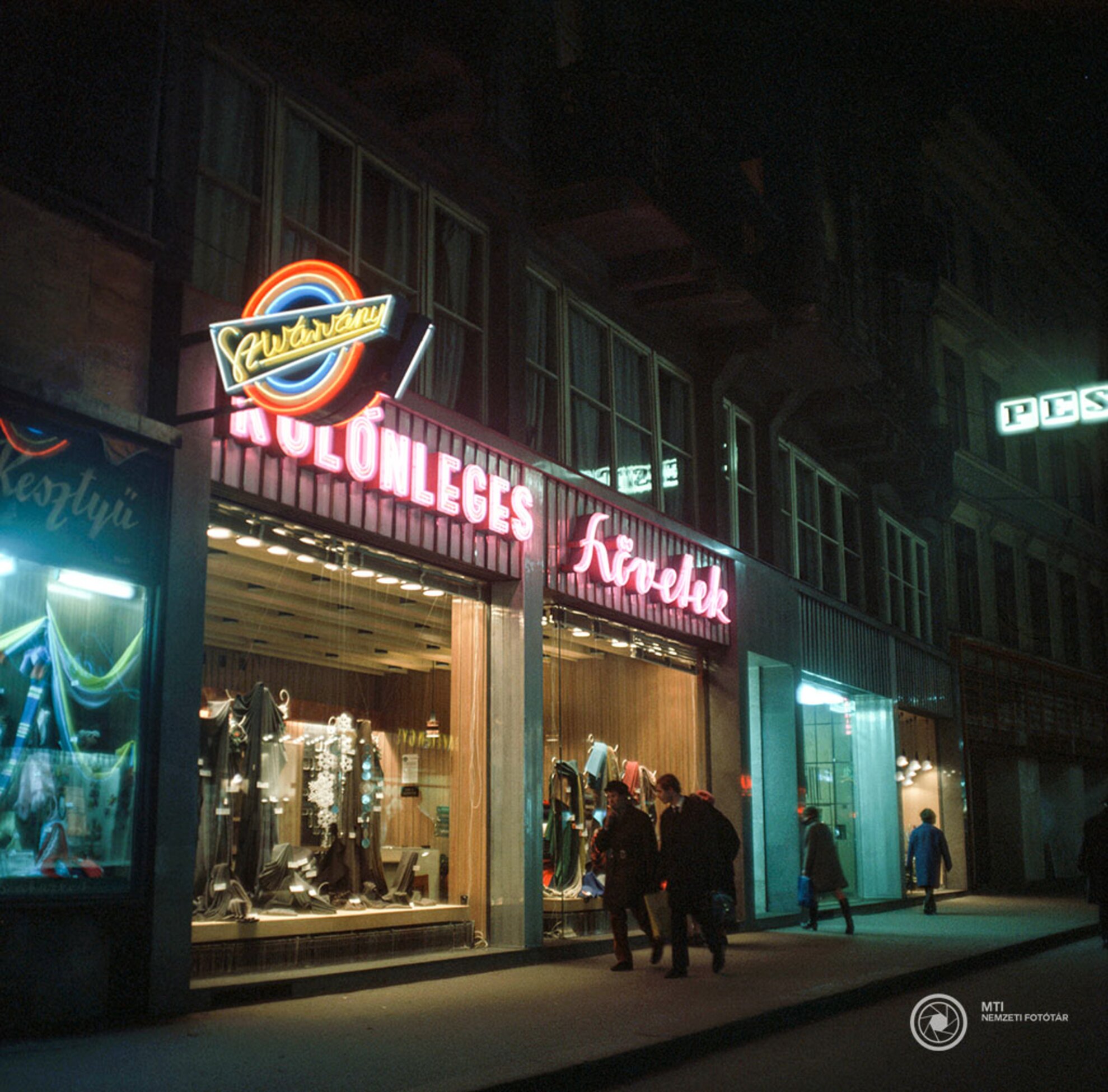

Do you have a favourite neon sign in Budapest? Perhaps the blue antiquarian owl, the Csemege sign in green and white, or the swan promising fresh laundry? Anyone who walks around Budapest will find these gems along the main streets of the city, and thanks to the MTVA Archive, we dig out photos of well-known, illuminated avenues and famous logos, and peek behind the curtain to see how they were made.

Where can pictures be found?

Researchers at MTVA – the Photo Gallery, Radio Archive, Sheet Music Archive and the Press and Motion Picture Archive – have been collating the memories of Hungarian history and culture since 1887. In the National Photo Gallery, you can view more than 270,000 photos online.

“Neon-bright Budapest, so wonderful when the evening comes. When a thousand lights come on, this colourful vision is almost a celestial phenomenon,” sang Németh Lehel. But behind this colourful façade is also the harsh reality of the Socialist era – the Communist authorities took advantage of the brilliance of neon. That is to say, night-time Pest beamed out Party propaganda.

The goal, of course, was to make Budapest more cosmopolitan – or, if nothing else, to at least rival the metropolises of the West in appearance. Today we are left with very little to remember these illuminated signs, or the ones that came before them. World War II had seen the destruction of Budapest’s rooftops and, as a consequence, the original neon dating back to 1908.

Between the two world wars, the Magyar Elektromos Művek gave a big boost to revitalising night lighting – not only illuminated advertisements, but also shop windows. Socialist leaders had already launched their neonisation programme in 1968, emphasising the need for Budapest to shine day and night.

As a result, cultural commentator Gyula Rózsa discussed the neon signs in somewhat unflattering terms in a lengthy column published in Budapest in 1971. Reading it with a modern eye is especially interesting:

"So what are the neon lights of Pest like? Flat. Figuratively, very many times; in the concrete sense, almost always. Let’s talk about concrete flatness first. Most of the neon signs in Pest are not neon signs at all, but illuminated signs. They are located exactly where the sign had been located for centuries: above a store entrance, on the same surface as a wall – and perform exactly the same function as the sign. They advertise what can be obtained underneath. The real neon sign, on the other hand, is as special as the sign was once: it jumps out of the wall perpendicularly, runs across rooftops and between rows of houses, links together like a strong chain by day, and raises its advertisements high at night in bright flaming letters. There are few of these left in Budapest."

What colour is real neon and how does it work?

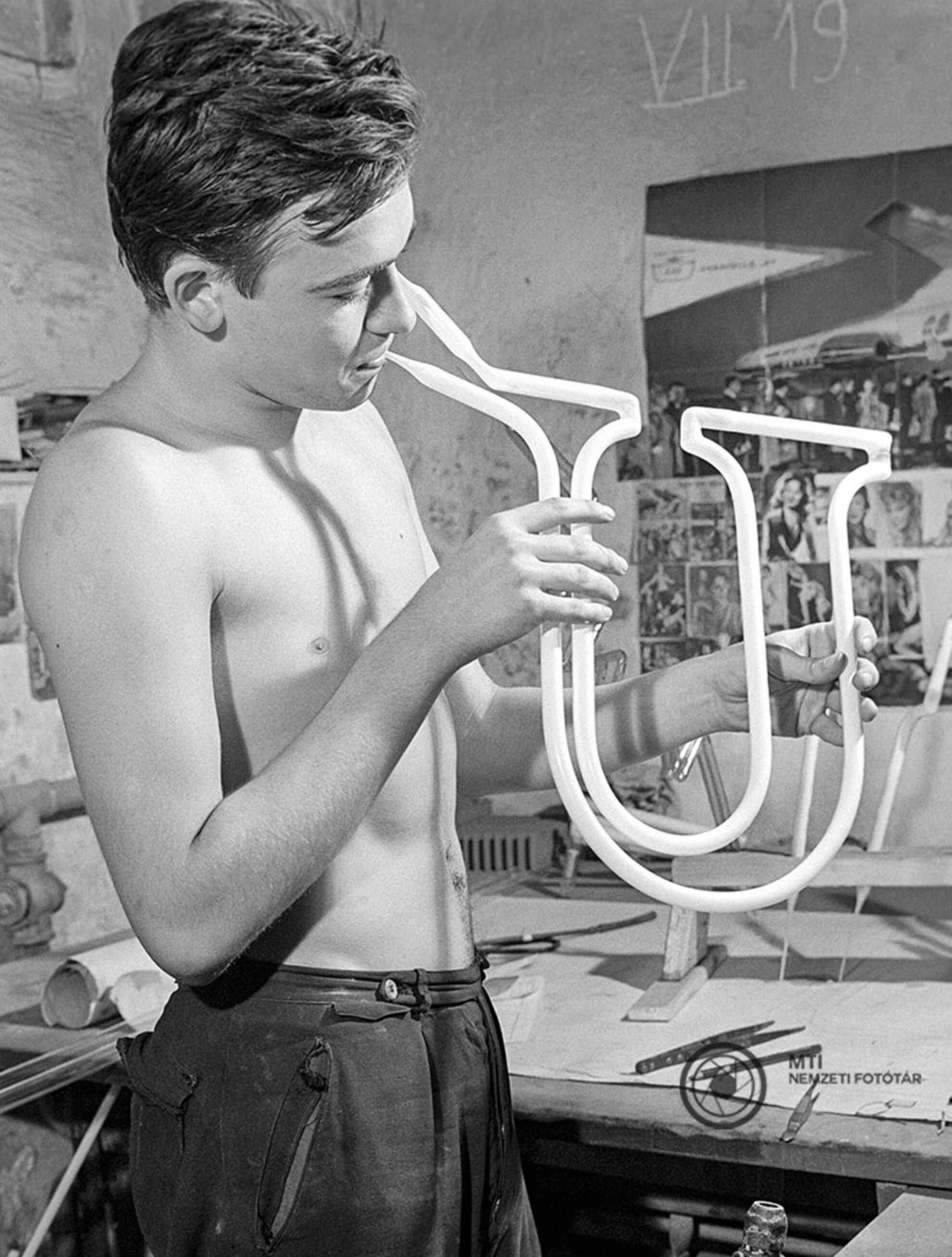

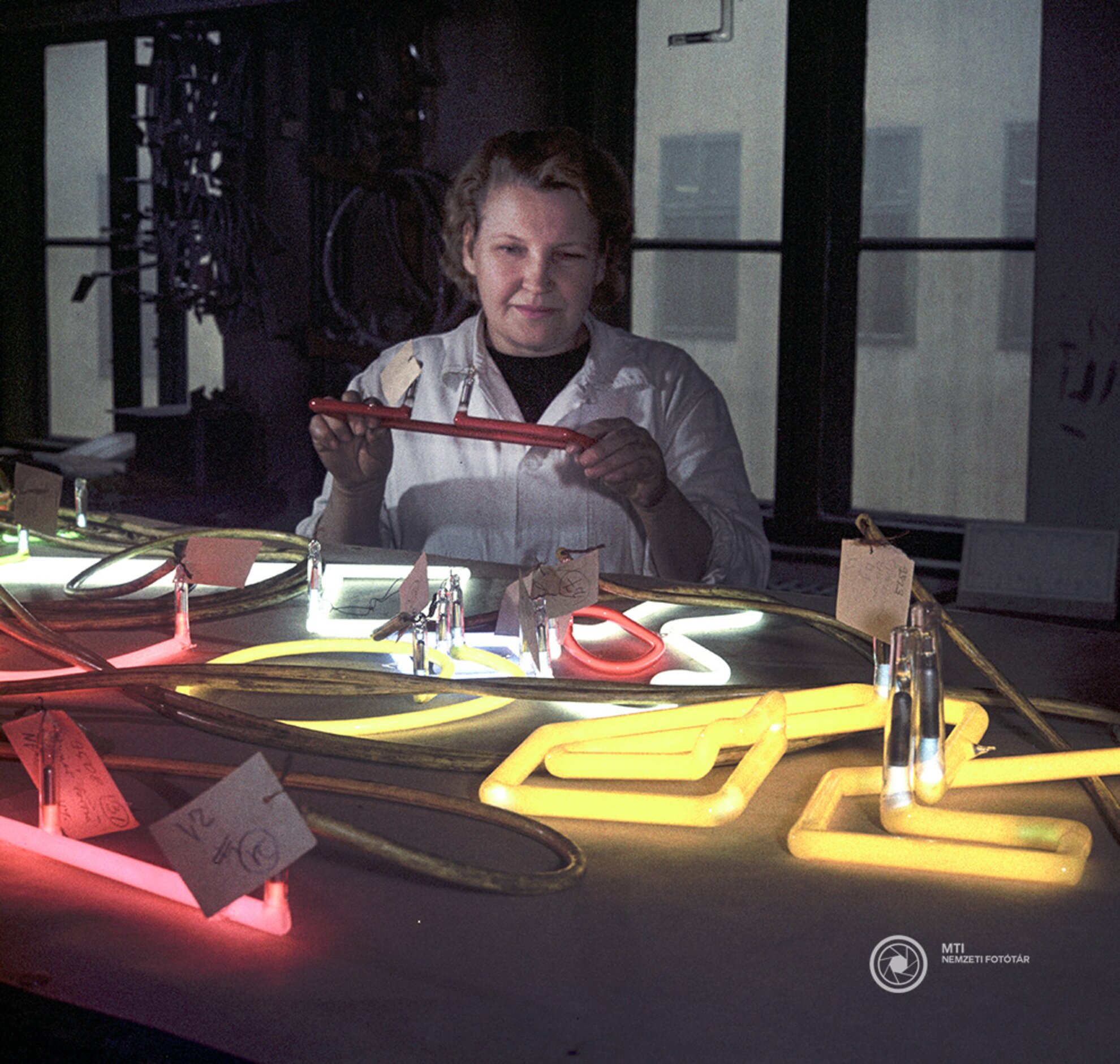

A neon tube is a luminaire filled with a low-pressure or thinned gas, in which the gas in the tube illuminates when a high voltage is applied to electrodes soldered to both ends of the glass tube. The discharge follows the exact shape of the pipe and its colour depends on the low pressure gas in the pipe. Carbon dioxide is white, mercury vapour is blue, helium is yellow, and neon gives a bright red light. The last was most commonly used in neon signs, lending its name to the other colours by proxy. Neon signs were first invented in the mid-19th century, when scientists discovered that electric bottles filled with different gasses create a colourful phenomenon. From here, the next step was simply to bend glass rods into any shape, and make unique inscriptions.

But the critics continued, despite neon’s general popularity. A writer in Népszabadság said in his article The Adolescent of Advertising in the 1970s:

“If we look at the neon signs of the evening cityscape, we see all the words: Restaurant, Shoe Store, Ibusz, Confectionery, Butcher, Fashion… Or nonsense. On November 7th Square [today's Oktogon] in Budapest, we see the illuminated letters EF in the most prominent spot. These two initials are the “advertisement” of the Elzett Factory… The competent authorities might say that it's because of foreigners, because of exports. Indeed, this may be true. The American capitalist walks the Grand Boulevard in the evening, sees the yellow EF, and immediately orders several wagon locks and padlocks.”

Of course, the inherent vein of capitalism made it difficult to square with the idea of a planned Socialist economy, so some middle ground had to be found. Public messages like “Buy ready-made clothes!” or “Shoes from the Shoe Store!” and “Don’t litter!” were also made and displayed.

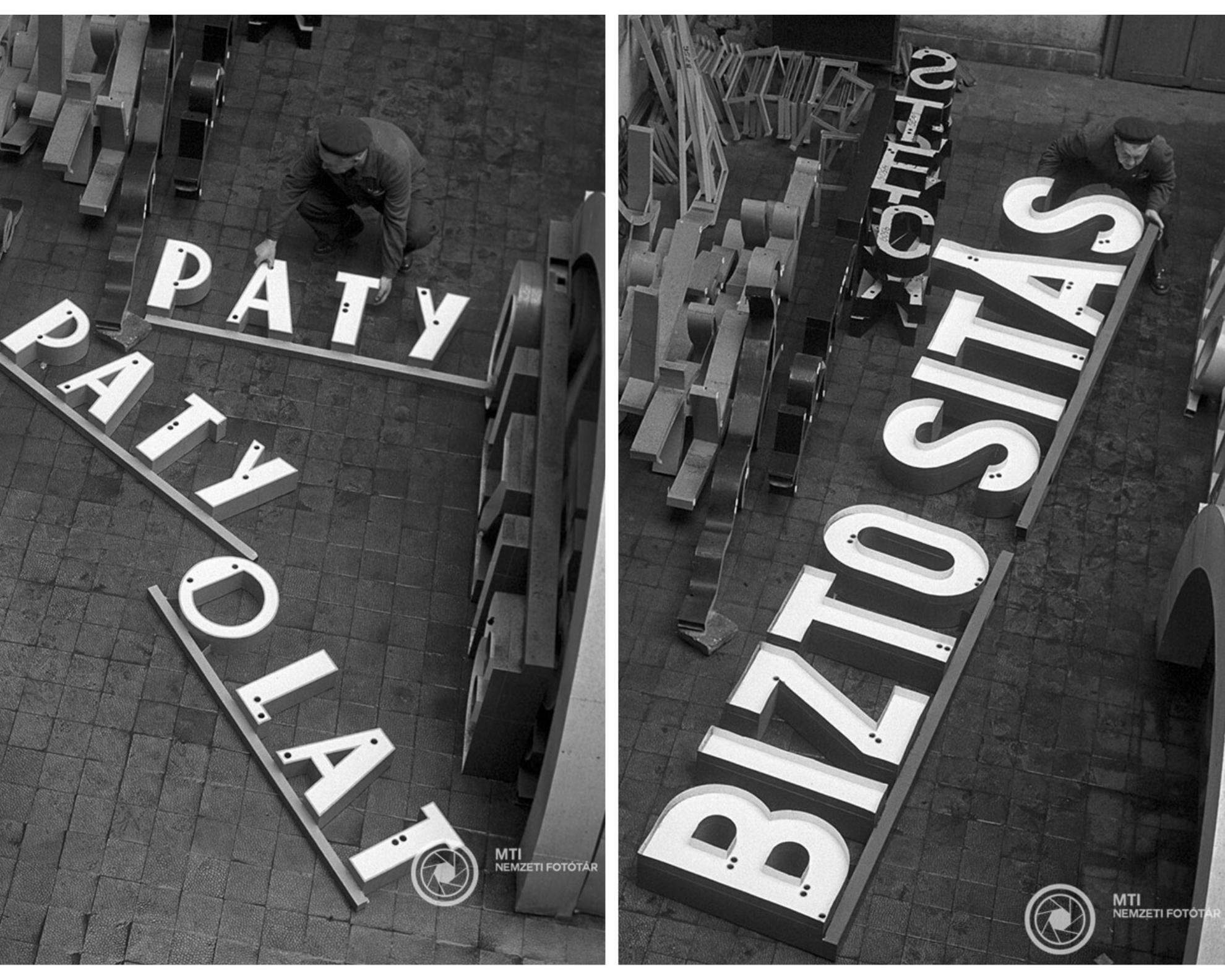

Despite the incongruous clash of capitalism and Socialism, the 1970s and ’80s are considered the golden age for neon advertising, with shops along major roads required to install neon, and larger state-owned companies were called upon to spend part of their budget on spectacular signs. Because of this, we still find most of the relics around railway stations and main thoroughfares like Rákóczi út, Üllői út and the Nagykörút. Lights along downtown Kígyó utca and Váci utca were also famous.

Signs were designed and manufactured within the ranks of the Metropolitan Neon Equipment Manufacturing Company, founded in 1949, who also made the necessary repairs. Although contemporary designers initially lacked creativity, wonderful pieces emerged from the hands of graphic artists, despite the standardisation of production. In 1977, the company was handed over to the United Incandescent Lamp and Electricity Co. Budapest's Metropolitan Mixed Service Company still maintains 2,500 neon devices, and produces neon signs to the tune of 15 million forints a year.

Today, little is left of these former advertisements, beyond the colourful pictures and memories. There have, of course, been efforts to save or at least catalogue them, such as the mini online exhibition Neon Budapest or the courtyard of the Museum of Electrical Engineering which displays some renovated classics.