When the Corvin Quarter, the mall and contemporary cityscape around it, began to take shape a decade ago, it replaced the tattered housing and apartment blocks where locals had lived for generations. In this latest pictorial series about Budapest’s vanished communities, we look at the southern edge of District VIII near the Grand Boulevard.

While the transformation of the Tabán and Óbuda belongs in the history books, the drastic change of colour behind the Corvin cinema has only taken place in the last decade. Yet the demolition and remodelling of the urban fabric here began as early as the early 1960s, when the decision was made to build high-rise blocks on Tömő utca and Práter utca.

While the disappearance of the Tabán or Óbuda evokes either a sense of loss about a romanticised past and their lost architectural value or a sense of relief, the collective urban memory concerning the Corvin Quarter is more nuanced.

Because some of the demolished buildings were in a truly deplorable condition – for as long as half a century, if not longer, they escaped any kind of renovation – as well as a neighbourhood burdened with social problems, few truly regret their disappearance. Nevertheless, it is difficult to make a clear value judgement as to whether the transformation with its enormous devastation can really be called a rehabilitation project, as there is really nothing left to rehabilitate. A whole new part of town has been created, wiping out any trace of the old.

Strictly speaking, the area is delineated and characterised by Práter utca, Tömő utca and Üllői út behind the Corvin cinema.

In the 19th century, this area was still a large suburb. Writer/journalist Mihály Táncsics hid away for years where today's Tömő utca begins, and where he also bought a huge garden plot. Writer Mór Jókai and Róza Laborfalvi, the significantly younger fiancée of famed novelist Gyula Krúdy, lived at nearby Baross utca 98. Krúdy’s collection Budapest vőlegénye ('Budapest’s Bridegroom') described the great pigsties of politician Frigyes Podmaniczky’s childhood here.

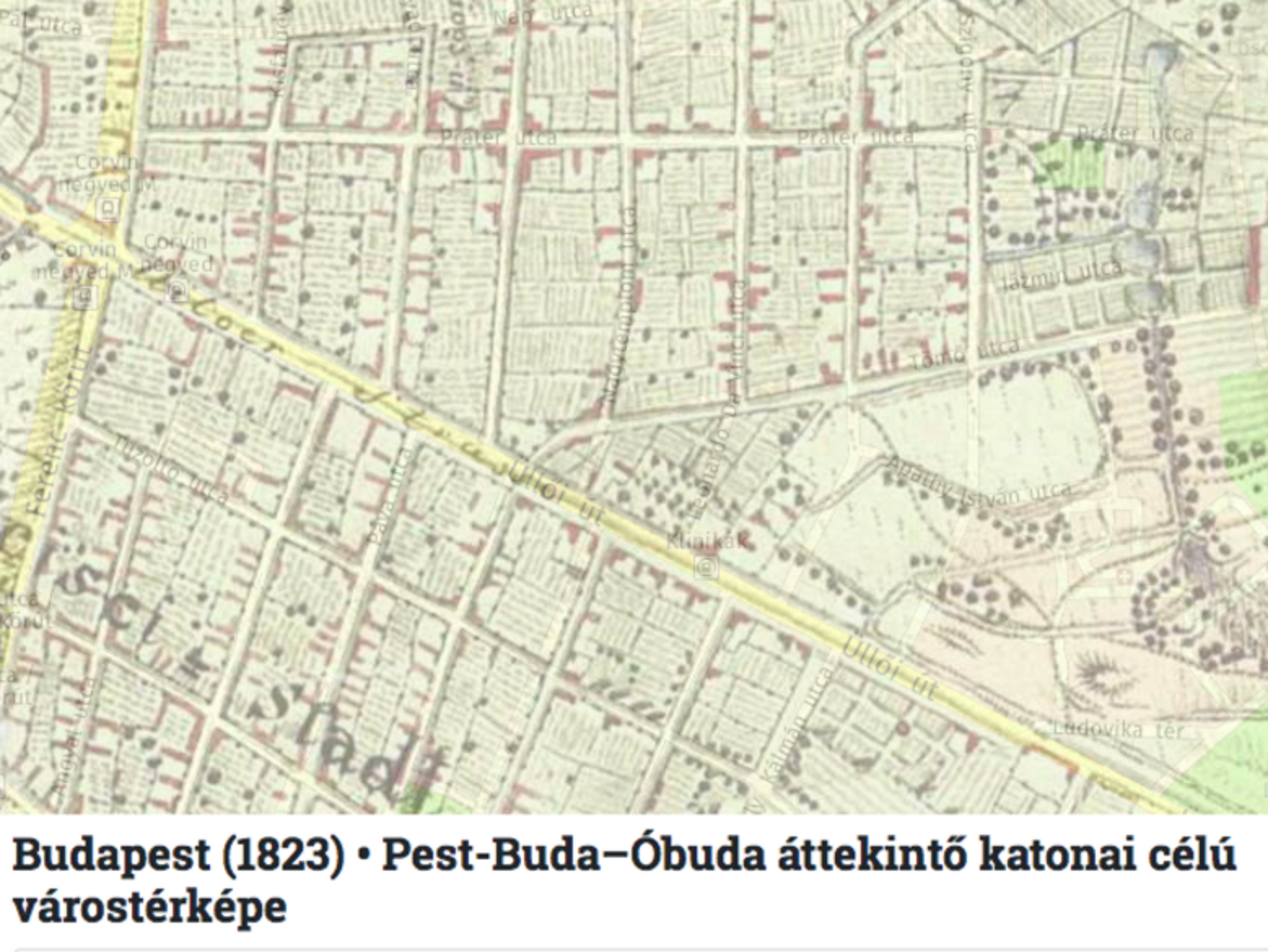

It is also clear from the old maps that there were only a few buildings here in 1823, many washed away by the Great Flood of 1838. By the 1870s, however, construction was coming thick and fast, and by the turn of the century, the area would be pretty much built up.

The houses showed a very mixed picture in terms of style and quality. In addition to the one-storey houses of relatively poor material, two- and three-storey apartment blocks, some of them elegant examples of late Classicist, Eclectic and Art Nouveau, alternated even within a street. Several members of the great architectural dynasties of the day designed houses here, such as Károly Hild, Ferenc Kasselik, Ágoston Pollack and Antal Gottgeb. Prior to World War II, most of the population consisted of artisans, lower-level officials, intellectuals and workers.

Budapest magazine (available for free in Hungarian on the Arcanum database) summarises the building stock in the area thus in 1972, in an interview with the chairman of Józsefváros Council:

“72 percent of these homes were built in the last century and, unfortunately, are not made of durable material. 40 percent of the buildings are single-storey and the proportion of those higher than two storeys is less than a quarter of the total. Sixty percent of the apartments consist of a single room and kitchen. Their floor area is small, but the ceilings are high. There are toilets on each floor – for six to eight to ten apartments – one or two in an open corridor. Most apartments do not have a bathroom. So the structure of each dwelling is one that forces the inhabitants here to live an outdated way of life.”

In 1964, Népszava announced that the oldest and most obsolete part of Józsefváros, between Jázmin utca and Tömő utca, would be emptied and demolished. As planning and then construction began, the blueprint was constantly modified and pushed back, as it turned out that no one in Hungary had much experience with an urban rehabilitation project of this size and complexity. Reconstruction of an already built-up area required much more money and caution – not only did the relocation of residents and the evacuation of homes and demolition consumed huge energy, but also the rebuilding of obsolete public facilities became a big dilemma behind the whole project.

Effective housing construction and redevelopment required the demolition of entire blocks, which meant that sometimes houses in reasonable condition were also sacrificed.

“This forced rehabilitation sometimes affects residential homes in decent condition, where artists, scientists and doctors living in old, spacious, three-room family homes can hardly be compensated in a new housing estate because they can’t find enough space for their huge antique furniture and long, well-stocked bookshelves” (Budapest Journal, 1970)

.

The first plan for the area was drawn up in 1962 and was adopted a year later. This referred to the southern parts of District VIII. In retrospect, it was full of unrealistic expectations, with the demolition of 5,800 homes and the construction of 8,200 new ones earmarked for the second and third five-year plans here.

In the early ’60s, houses built with traditional technology were still being designed, the model for future construction illustrated by the József Attila housing estate. But the technical, economic and political changes that took place over the decade, the commissioning of communal blocks, the New Economic Mechanism of 1968) significantly modified those older concepts.

Of the planned five 17-storey tower buildings on Tömő utca, three were eventually completed, the calculations continuously chopped and changed until 192 flats were handed over by the end of 1970. After significant delays, residents were able to move into the first house in May 1970, but two months later the list of errors and complaints ran for 70 pages and cost a million forints’ worth of damage. (The average salary at the time was under or around 2,000 forints.) The walls were damp, the wallpaper was peeling off, there were gaping gaps in the joints – even the strictly controlled contemporary press barked loudly at the scandal.

Over the decade, three more blocks were built on Práter utca, and finally, the 10- to 17-storey blocks of prefabricated concrete on Illés utca and Szigony utca, along with clinics, nurseries, kindergartens, schools and other communal institutions for the area.

But as soon as this protracted and unsuccessful project was complete, the fate of the remaining houses and residents of the area was wiped from the agenda, and any further reconstruction here forgotten about.

Before the fall of Communism in 1989, urban planner Anna Perczel drew up a thorough zoning blueprint for the area between Üllői út and Baross utca, up to Illés utca. Even though it was backed up with sociological research and value assessment, it came to nothing. Rather than complete demolition, it would have meant keeping a significant part of the building stock and only loosening the urban fabric to the required size and green walkways in the gaps, according to a 2005 article by Magyar Narancs.

The municipality initially thought of a block reconstruction similar to that of Ferencváros (much criticised since then), but in the end the most financially viable solution won out: the resultant Corvin Quarter, initially named Corvin-Szigony project.

The first demolitions began in the autumn of 2005, 22 houses in a block bordered by Práter utca, Vajdahunyad utca and Futó utca.

“In their place is a huge empty plot. The Tabán demolition was small by comparison. Life was miserable there too, yet today everyone regrets that they didn’t leave at least one or two classic examples of housing there. I wouldn’t like the same to happen in Józsefváros.”

This is how Lajos Csordás describes the scene at the time in Budapest magazine, which was also lamenting the lost cityscape. As a result of the transformation, considered the largest real-estate development project in Central Europe, almost nothing was left of this part of town from a century ago, once also called the Industrial Quarter.

It is interesting to look back now that original plans called for a training centre for the Franz Liszt Music Academy to be factored in, but the mini-campuses of SOTE and Pázmány universities ruled it out, structure-wise.

Today, the area has been almost completely repositioned around the edifices created by global developers Futureál, as the ground-floor houses are replaced by plazas, high-tech office buildings, residential parks and restaurants. The Nokia HQ was completed by the beginning of 2017, which is one of the finishing elements of the decade-long development of the Corvin Quarter and the iconic visual element that closes the promenade together with the Corvin Technology & Science Park and the Corvin 7 office buildings on Szigony utca.

The last bastion of the area, preserving its old atmosphere and history, disappeared when alternative bar and community centre Gólya moved from Bókay János utca in 2019. Its closure is a good example of the gentrification and rehabilitation processes taking place, the venue occupying a former restaurant building opened in 1906. More than just a great party spot, it hosted important social projects, workshops and events involving the local community.

These can now be found further away, at Orczy tér, and the original ground-floor building, the last survivor in the Prater-Tömő-Szigony Bermuda Triangle, is being demolished so that a new residential block can be built in its place.